Birds of Prey

28 Simon Winder, Germania: A Personal History of Germans Ancient and Modern, (London, 2010), p. 17.

29 Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory, (New York, 1995), pp. 75–120.

30 Barbara Ehrenreich, Blood Rites: Origins and History of the Passions of War, (London, 2011).

31 Simon Harrison, Dark Trophies: Hunting and the Enemy Body in Modern War, (New York, 2014).

32 See Michel Foucault, The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception, trans. A.M.Sheridan Smith, (New York, 1994).

33 Richard Holmes, Riding The Retreat: Mons to the Marne—1914 Revisited, (London, 2007), p. ix.

34 Peter Hennessey, The Junior Officers’ Reading Club: Killing Time and Fighting Wars, (London, 2010).

35 Thomas Kühne, Kameradschaft: Die Soldaten des nationalsozialistischen Krieges und das 20. Jahrhundert, (Göttingen, 2006). See also Kühne, Belonging and Genocide. Hitler’s Community 1918–1945, (New Haven, 2010) and ‘Kameradschaft – “das Beste im Leben des Mannes”, Die deutschen Soldaten des Zweiten Weltkrieges in erfahrungs- und geschlechtergeschichtlicher Perspektive,’ Geschichte und Gesellschaft 22 (1996) S.504–529, and Kühne, The Rise and Fall of Comradeship: Hitler’s Soldiers, Mass Bonding and Mass Violence in the Twentieth Century, (Cambridge, 2017).

36 TNA, WO 208/3608 CSDIC SIR 1329, Establishment of a Jgdko by Secret order of the Befehlshaber Südost, interrogation of UFF’S Kotschy and Boscmeinen, 13 December 1944. WO 208/3979, A Study of German Military Training, Combined Services, May 1946.

37 TNA, WO 208/3000, ‘The German Squad In Combat, Military’, Intelligence Service, US War Department, Washington DC, 25 January 1943. WO 208/3230, US Army Pamphlet 20-231, ‘Combat in Russian Forests and Swamps’, Department of the Army, July 1951. Military Intelligence Service, No.15, The German Rifle Company, (Washington DC, 1942), 1942, partial translation of Ludwig Queckbörner, Die Schützen-Kompanie: Ein handbuch für den Dienstunterricht, (Berlin, 1939).

38 Edward A. Shils and Morris Janowitz, ‘Cohesion and Disintegration in the Wehrmacht in World War II,’ The Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 12, No. 2 (Summer, 1948), pp. 280–315.

39 Lord Russell, of Liverpool, The Scourge of the Swastika, (London, 1954); Russell was a judge advocate officer and had worked on numerous war crimes trials.

40 For example, Max Hastings, Overlord, (London, 1986).

41 Martin van Creveld, Fighting Power: German and U.S. Army Performance 1939–1945, (London, 1983).

42 Bartov, Barbarisation, passim.

43 Institute of Historical Research: School of Advanced Study, University of London, German History seminar, Professor Omer Bartov, 21 May 1997.

44 The Wiener Holocaust Library, lecture ‘Intimate Killing’, 26 February 1999 presentation of Joanna Bourke, The Intimate History of Killing, (London, 1999).

45 Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish, (London, 1991).

46 Arbeitskreis Militärgeschichte e.V., Essen conference, August 1999.

47 In particular: Henry Metelmann (panzer—Guildford), Heinrich Schreiber (infantry-Aachen), Paul S** (Luftwaffe-Magdeburg), Frederich Baumann (infantry-Berlin) and Boso L**(Waffen-SS).

48 Philip W. Blood, ‘Securing Hitler’s Lebensraum: the Luftwaffe and the forest of Białowieźa 1942–4’, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, (Oxford, 2010).

An Aide-Mémoire:

Reading Maps Like German soldiers

A.J.P. Taylor once wrote: ‘Every German frontier is artificial, therefore impermanent; that is the permanence of German geography.’1 The Luftwaffe’s mission in Białowieźa was part of a policy of erecting a permanent frontier on the eastern borderlands. Beyond this ‘new’ frontier lay Belorussia, Soviet Russia, and Ukraine, in effect Hitler’s Lebensraum empire. A permanent eastern frontier represented a geopolitical goal for the Nazis. Göring’s three-part plan to bring this about included racial population engineering in Białowieźa. The first and fundamental goal was to bring about the eradication of Eastern European Jewry. The second goal involved the reduction and deportation of Slavs, dubbed Untermensch (sub-humans), from the large group of forest settlements. In the third stage, Göring’s plan called for the settlement of ethnic Germans, mostly repatriated from the east. Hitler’s invasion of Soviet Russia complicated this plan, slicing through the former Pale of Settlement from Tsarist times, a vast territory that was still homeland to several millions of Jews.

The problem I had to overcome concerned the relationship between the Landser and the environment. How did 650 German soldiers effectively secure 256,000 hectares of Nazi-occupied Białowieźa? The command and control of space or terrain have always been a strategic concern of nations, colonisers, army commanders, and security forces. During the Iraq insurgency (2003–11), the American army was forced to adopt a ‘population-centric’ strategy.2 For this research, the first step was to recognise that the expansion of the Białowieźa Forest, by the Nazis, was the creation of a frontier security zone. I called this frontier security zone the Białowieźa arena, to reflect the full extent of Göring’s territorial ambitions in this region. This arena was secured on the basis of a ratio of one soldier per 1.52 square miles. How did the Germans fill the command and control of space, and was it effective? These questions challenged my research because they fundamentally alter our understanding of how Nazi occupation and colonisation was practised. In 2010, the research began the application of Historical GIS to solve these challenges and look afresh at how the Germans organised security. Consequently, this chapter is an aide-mémoire to the GIS maps that were generated and are included in full within the narrative.

I. The Nazis and military geography

Nazi aspirations were particularly focused on the frontier of East Prussia. Following an ultimatum to Lithuania, in March 1939, Memelland (today—Klaijpéda in Lithuania) was annexed, an area covering 3,000 square kilometres.3 After Memelland, there were more acquisitions of former Polish territory in the south-east, named Regierungsbezirk Zichenau. This added another 12,000 square kilometres. Further annexations increased the state’s landmass to 52,731 square kilometres (5,270,000 hectares), with a total population of 3,336,771. In July 1941, three forests became the anchors for further expansions. The Elchwald (Elk forest) designated Forstamt Tawellningken (due west of Tilsit and running north/south along the Kupisches Haff) was expanded to 100,000 hectares with localized annexations. The Kaiser’s former hunting estate at Rominten was increased to 200,000 hectares with Polish acquisitions. The third was Białowieźa forest, a trophy from the Nazi invasion of Soviet Russia in June 1941. Between 1915 and 1939, the approximate forest area was 160,000 hectares. Göring’s plan required an increase of 90,000 hectares, increasing the gross area of the forest to 256,000 hectares. One hectare is equivalent to Trafalgar Square (London) or the area of an American football stadium. Shenandoah National Park boasts 200,000 acres, which converts to 81,000 hectares. This brought the eastern forest plan to a gigantic total of 560,000 hectares. In forest mass alone, East Prussia’s 1933 borders had increased by twenty-five per cent.4 This occupation area, including Białowieźa, was designated Bezirk Bialystok and administered from Königsberg as domestic territory.

Where this expansionism was leading is not altogether clear, since Nazi dogma, strategic ambitions, and geopolitical annexations were all at odds. Erich Koch, as ruling Nazi Gauleiter of East Prussia, not only presided over all these expansions but was also gifted with the Reichskommissariat Ukraine. Koch was turned into an overlord of a racialized colonial frontier. In effect, East Prussia and Bezirk Bialystok symbolised the fulfilment of the eastern frontier of the Greater German Reich—virtually replicating the brief existence of New East Prussia (1795–1806). The annexation of Ukraine, however, represented a fulfilment of Hitler’s Lebensraum ambitions. Thus, Bezirk Bialystok was also a geopolitical land bridge between Nazi Lebensraum and an Imperial style Greater German Reich. The creation of a colossal forest wilderness, dubbed an Urwald (primitive forest), also had strategic and cultural implications. There was a belief in the defensive military qualities of forest wilderness, which will be discussed later. Culturally, the creation of a massive forest pointed to the recreation of the ancient forests of Germania. In parallel, there were biological-zoological ambitions to recreate long-extinct animals, like the Aurochs that once roamed the ancient forests. In effect, Zoologists had institutionalised the notion of the racialized game. These mindsets lay behind the German occupation’ transformation of Białowieźa into a wilderness arena, however, even this story was loaded with contradictions.

In the military context, the expansion of the eastern frontier produced significant security administration requirements of a colonising scale, rather than for a political annexation. The challenge for the military-security services was to meet the Nazi goal. To excel in military geography was the German officers’ mantra. Field Marshall Schlieffen’s staff rides, his battlefield tours, were lessons in reading maps to better understand the nature of battle.5 Göring’s fitness for command could be partly gauged by his map skills and understanding of the terrain. In the first instance, he had acquired knowledge as a user of military geography. As an officer cadet, he was schooled in terrain and geography; as an airman-observer, he was an expert of map interpretation; and as a squadron leader conducted his command through maps—but was he suited to command-control Białowieźa from the comfort of Rominten? In the Second World War, German military cartographers not only plotted the movements of armies and the positions of enemies, but also the distribution of populations and strategic raw materials. The search and acquisition of local information were paramount to military and civilian occupations. Consequently, the daily production of maps was essential to both warfare and racial engineering. By 1942–43, it is estimated were that the armies in the east were printing and distributing upwards of 25,000 maps per day.6

German military geography was not well documented to assist this research,7 but an indication of the German cartographical system can be located in other sources. In July 1945, British Army intelligence interrogated a senior NCO from the Wehrmacht’s military geography branch. His interrogators isolated the German administration of military geography as the focus of their questions. They learned that Lieutenant General Gerlach-Hans Hemmerich (1879–1969) was reactivated in October 1936 as Chief of Abteilung für Kriegskarten- und Vermessungswesen, the Mapping and Surveying department within the Chief of Staff of the Army (OKH). He remained chief of army mapping until April 1945. The department was designated MIL-GEO, with its head office in Berlin and with smaller satellite departments dispersed throughout the army. Maps remained its primary mission throughout the war.8 Following the outbreak of war, MIL-GEO’s offices and personnel expanded through the conscription of elderly professors and civilians with geographical expertise. The Berlin university system was particularly important in providing staff. Professors also recommended good students for staff posts, and the army designated them Heeresbeamter, a military-civil service rank. This process of conscription was later extended to geography schoolteachers and local government surveyors. Following Germany’s early conquests, the MIL-GEO established outposts in most occupied cities. The scope of their work extended to gathering information recorded on a card index system. The breadth of data collected included physical geography, economics, water sources, traffic routes, roads, and anything deemed essential to military operations. Once compiled into maps and reports, they were packaged in comprehensive volumes and distributed to the higher commands as topographical intelligence. In effect, each high command of the army received a collection of detailed maps and cartographical information to conduct operations.

The British interrogators also raised questions about (Lw) Lieutenant Otto Schulz-Kampfhenkel (1910–1989), chief of the Forschungstaffel zbV des OKW. They learned that Schultz-Kampfhenkel was a geographer and was Göring’s special advisor on political-military geography. Before the war, he founded Forschungsgruppe-Schultz-Kampfhenkel, a consultancy with a reputation for applying a ‘total approach’ to explorations and surveys. He led an anthropological-cartographical expedition to Amazonia (1935–37) in a joint venture organised by the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Biologie and Brazil’s National Museum.9 The expedition’s mission was to examine Urwald and understand its special qualities. During the war, his Forschungstaffel was turned into a small office, attached to the OKW, and called Sonderkommando Dora.10 Schulz-Kampfhenkel was also tasked with exploring and surveying parts of North Africa. As the chief exponent of Urwald, Schultz-Kampfhenkel advocated the incorporation of forests into the German national defence system. While there was a sacred relationship between the German hunt and Urwald, Schulz-Kampfhenkel’s ideas for a forested border in the east gained a powerful grip on Nazi homeland security. Schulz-Kampfhenkel’s ‘hidden-hand’ was behind Göring’s plans for Białowieźa. In effect, the forest was set to become part of Germany’s national boundaries, and with a central strategic purpose of defence.

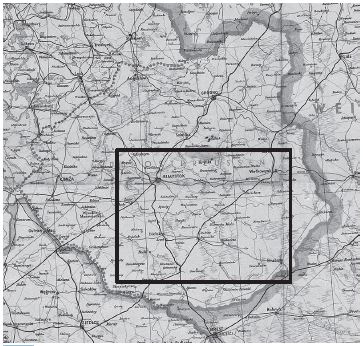

Map 2: Bezirk Bialystok circa 1944.

The area within the black box approximates to the Białowieźa security arena discussed in this book.

Source: Wikicommons|Public Domain

The Luftwaffe’s Białowieźa operation’s map the Karte des Urwaldes Bialowies is held by the Bundesarchiv-Militarärchiv. The map has a 1:100,000 scale and was produced in digital format of six sections. When put together they filled a small lecture room. The map had a legend that included the positions of troops, strongpoints, command posts, and wireless posts. During the war, the map was arranged as a single item on a large map-table in the Tsar’s former hunting palace, that served as the battalion’s headquarters. Trying to reconstruct the battalion’s cartographical activity was impossible: trying to locate the position of companies and squads beyond the major towns was a ‘hit and miss’ exercise. A conundrum materialized that came from not being able to integrate the map with the documents. The operational administration and orderly filing of the Luftwaffe combat reports contrasted with the content of the reports, that implied random, haphazard, and chaotic killing. Actions were too far at odds with reporting. The actions in the combat reports did not reflect the known understanding of the German way of war or small-unit actions. The maps were the primary form of command and control for German operations, and were pertinent to the Białowieźa story. Reports without the maps were largely incoherent beyond killing, fighting, or deporting. If the behaviour of the Germans was deliberate, it could only be proven by unlocking the map codes. A neutral, and important, issue within the documents, was the geographical references buried within the combat reports. These references could not be disputed. Attempting to reconstruct cartographical movements with this map approved impractical with marginal results. This confirmed Hobsbawm’s dictum that grassroots history has its challenges: it ‘doesn’t produce quick results, but requires elaborate, time-consuming and expensive processing.’11

II. The science of maps

The aphorism ‘a map is worth a thousand words’ was never more pertinent than in the research behind this book. The conversion to historical GIS (Geographical Information System) was a drawn-out process. Today, GIS is routinely applied to a full range of historical fields, including the Holocaust.12 Before that time, we relied on discussions with the geographers at the Bundesarchiv to try to understand how the maps were used. There was some confusion because there was no working reference to how the Germans had used the maps. In discussions with Bettina Wunderling, a qualified GIS technician, we examined the theory of applying alternative methods to unlock the maps and connect them to the war diary. We agreed upon an experiment that should use the digitized map of Karte des Urwaldes Bialowies as the platform for conducting GIS-based forensic analyses.13 Transferring the research to a scientific basis was not an entirely alien prospect. During my MBA at Aston Business School, assignments involved quantitative analysis of large data sets, computer programming, systems engineering, and design, and had devised a research method for managing large quantities of diverse information. There were hidden benefits that Richard Holmes recognised, that elements of my MBA, which included management systems, organisational theory, and social psychology, would help to broaden the historical research.

In the second decade of the Twenty-First Century, it might appear strange to discuss working with Historical GIS in a large area of Europe, without geo-referencing. The challenge was to combine old map skills with the new science of mapping. The first stage involved learning by doing. Initially, little could be done because the ‘Bialowies’ map lacked spatial coordinates and the projection was unknown. These are common problems when working with historical maps. As a consequence, it was not possible to use the map in a GIS system or make visualizations and analyses. We visited the Mammal Institute, in the UNESCO World Heritage park of Białowieźa in eastern Poland, and Dr. Tomasz Samojlik. He showed us the institute’s collection of historical maps and five highly detailed maps drafted in the 1920s by Polish geographers. After some preliminary examination, we realised the Germans had based their military map on the Polish maps. Tomasz provided the projections and coordinates to digitize these maps. In the search for comparative national/local maps from 1941, we found a consistent absence of borders between Białowieźa and East Prussia to the north, which indicated political annexation. A military map of the Pinsk-Pruzhany area to the south, drafted in July 1943, confirmed a national boundary towards the east. This confirmed the territorial expansion of East Prussia, as the national frontier with a wilderness bastion to the Greater German Reich in the east.14

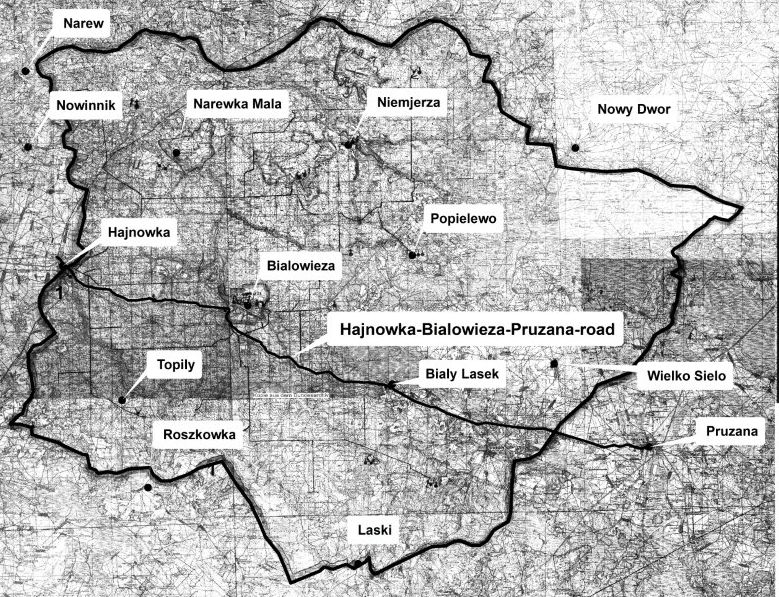

Digital Map 3: Luftwaffen Karte des Urwaldes Bialowies.

© Bettina Wunderling.15

In 2009, it was virtually impossible to identify the lost villages and the scenes of many incidents in the forest. The preparations for being able to conduct forensic modelling came from comparing the documentary records to the application of historical GIS to research and using textbooks as guidebooks. There were few textbooks about GIS in historical research or how to apply GIS to forensic analysis. One of the few was published by ESRI Press, the in-house publishing arm of the leading GIS software company.16 The chapters were instructive. One chapter examined the importance of maps in GIS.17 The authors explained the values of reliability and accuracy in GIS modelling. They highlighted the visual impact of terrain. A second chapter focused on battlefields and detailed the essential processes from fieldwork to desktop mapping.18 Another important book confirmed the peculiarities of working with both historical data and maps.19A visit to Białowieźa was necessary to log important data into the database: the positions of old photographs, specific map references, and geo-reference points. The processing of the Luftwaffe map sections was a laborious and time-consuming task that involved adjusting different maps to a single useable map. Bettina began an advanced GIS course, and the department allowed the process of digitisation and the GIS mapping to be tested under university conditions. A high degree of expertise emerged that the university endorsed with a letter of commendation.20 Bettina began to incorporate more advanced methods of historical GIS.21To better understand the full breadth of Historical GIS and the basic operating principles, there were online seminars available to beginners. In May 2013, I joined an historical GIS course hosted by the Institute of Historical Research, London University. This involved working through an ArcGIS project in the classroom. This course reinforced the importance of managing several issues, including, digi-maps, geo-referencing, vector data and coordinates, symbolising data, pixelization, spatiality, data parcels, cartograms, and copyright.22 By the completion of the first stage and the preparatory work, we had produced a map (Map 3 below) in a digital, georeferenced form that would make possible a variety of analyses.

The second stage involved identifying data from the documents or qualitative content to form into specific layers. In a sense, this was akin to unpicking the spaghetti of data and trying to isolate common data sets. The significance of GIS is the integration of seemingly unrelated data and its reordering into meaningful information. Layers were identified from different sources. Infrastructure like roads, swamps, railways, roads, bridges, farms, and estates were digitized from the original Polish maps. The Luftwaffe had drawn information on their maps, such as the position of strongpoints, companies, and Jagdkommando. This data was integrated with the Polish maps and digitized. The next task involved data mining from the surviving diaries of the Luftwaffe. There were two defined periods with different commanders, tactics, and dogma. This was a very time-consuming process because of the form of handwriting. Sütterlin is not taught in German schools today, but was widely utilised during the war. Once the barrier of the handwriting was overcome, page by page, line by line, (about 120 pages) we were able to present the results for review by a German veteran, who explained more nuances about that writing form under combat conditions. The overall outcome was a wealth of details and data. This led to multiple complex layering and we began to compare colour pixelization against the black-white map format. We opted for the latter. There were so many map options we decided to compile a series of test maps. Copies of these maps were sent to the late Dr. Joe White and his team, at the US Holocaust Memorial and Museum in Washington DC in 2013 for an evaluation. We also began to examine the nature of time and its impact on the events. A partial experiment, involving multiple modelling was used to test the visualisation of progressive troop movement and patrols through segments of the forest. The outcome came down to tracking platoon, squad, and Jagdkommando movements, by minutes, hours, or days, depending upon the detail of supporting data.

Stage three involved formulating forensic analyses based upon the findings from the GIS layering tests. The key forensic mappings was classified under: the orders of battle or deployment of companies; the Bandenbekämpfung actions; population engineering; Judenjagd or Jew hunts; and larger operations. A 3-D model was drawn from the isolines of the maps. The outcomes of the analyses confirmed the working value of Historical GIS in a forensic dimension. How we presented and organized this evidence became crucial because the format selected would profile the narrative. The choices were: a military history format, the judgemental form of a war crime investigation, or a socio-cultural study of violence. In discussions about Bandenbekämpfung with retired US Army General Richard Trefry, comparisons emerged from Vietnam and Iraq.23 He recommended the US Army’s official report on My Lai as a structural model. The report incorporated a full schedule of maps and movement diagrams, which enabled comparisons with the logic behind the GIS mapping.24 Comparing post-war atrocities, such as My Lai, with Bandenbekämpfung was not the intention, but following the structure of the report of integrating maps in the narrative did seem appropriate. In 2013, a test of the mapping and narrative was made of the area where Siegfried Adams was killed in combat in June 1943 (see epilogue). The geo-data, geo-references, and qualitative content proved complete for Adams. The results were spectacularly successful.