Birds of Prey

A final test was to compare the findings to the content from Geographies of the Holocaust. This book had set the benchmark for applying historical GIS to the Holocaust. The book revealed the potential for a multidisciplinary approach to the Holocaust, but also the limitations when applied to military matters, and both are due to issues of spatiality. In a chapter about hunting Jews, the application of GIS was focused on time and space. The base data required a large body of data statistics including names, homes, mass deportations, and camps. In another chapter devoted to the killing grounds, the authors attempted to reconstruct the specialities of hunting Jews in Belarus. The chapter highlighted the formulation of ‘locational models of killing’, with GIS applied to map the movement patterns of killing units. There was graphical presentation of killings, a diagrammatic schedule of killings by time, and functional images of soldiery duties, which culminated in the summary—testimony, technology, and terrain. In both chapters there was an absence of integration and limited forensic outcomes. If the same methods had been applied to Białowieźa, they would have produced only minimal results.25 This did not reflect against the authors, but rather explained how different documentary evidence requires different historical GIS methods. We concluded that Historical GIS had unlocked the Luftwaffe’s mission and methods in Białowieźa. Historical GIS served three purposes: firstly, it had highlighted the prominent geographical features of the forest. Secondly, it recreated all military movements by timelines, operations, and outcomes, such as individual crimes. A deeper forensic analysis was achieved from mapping and visualising the effects of discipline, the routine, and orderliness of the killings. Thirdly, GIS exposed how a national political frontier divided responsibilities, but also explained the internal rivalries. In conclusion, GIS had exposed a grandiose Nazi scheme, Göring’s ambitions, and the soldiers’ behaviour—probably for the first time since 1945.

III. The GIS maps

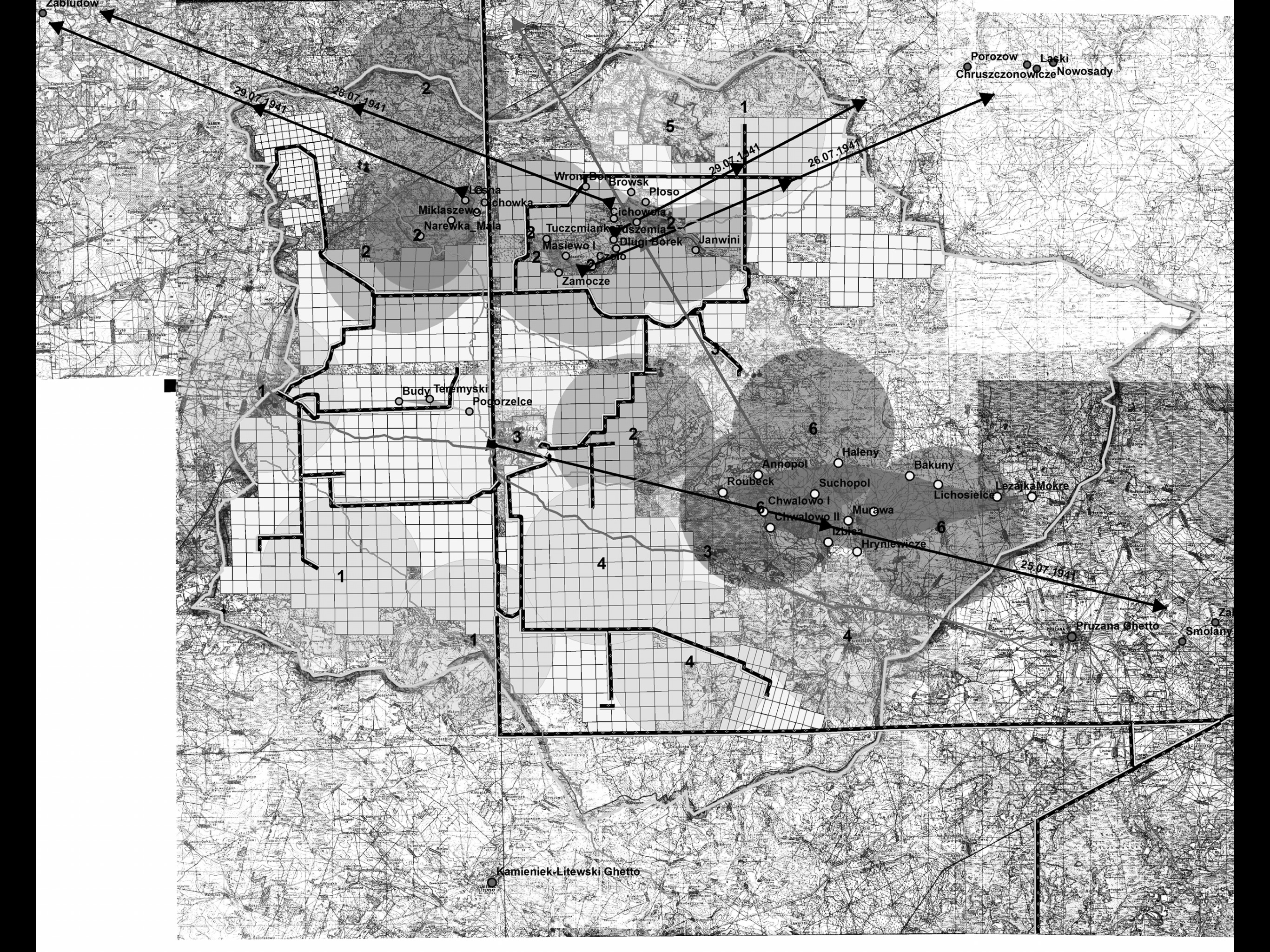

This book contains more than twenty maps, the majority are from the Historical GIS analyses. The map below (uncaptioned) is an example of our first results. This is a composite map and although highly detailed it’s also a picture of information overload caused by the density of layering and grayscale. The ‘buffers’, or roundels, represent patrol distances within company areas and also radio signals ranges for small wireless devices. Arrow lines give general directions of patrols and deportations. The Germans incorporated the Jagen system, which represented a square kilometre ground—reflected in the grid pattern. This was an old Tsarist form of measurment used in Białowieźa for forestry management. The squares were mapped into the German maps and renamed Jagen. All of these factors have remained constant. However, in an effort to reduce the sense of clutter, we experimented with single layer maps and then with specific theme maps.

The solution we finally decided to accept were specific to the general findings from the research and forensic in design. The maps were finalised after series of experiments with colour, black and white, multiple layering, and single layer analysis. The GIS maps are in a specific set of representations: the orders of battle or deployment of companies (maps: 3, 4, 12, 13, 14, 20); the Bandenbekämpfung actions (6, 10, 16, 17); population engineering (5); Judenjagd (7,8,9, 11, 18); and larger operations (19, 21).

Alongside the GIS maps, the number of photographs were selected to contrast contemporary images of war with postwar memory. The aim was to visualize the concept of 'victims, bystanders and perpetrators' so prominent in Holocaust literature.

The conjunction of memory and mapping represents how communities co-exist within a landscape scarred by war and the Holocaust. Memories cast in the stone memorials stand in all Eastern European and Russian communities; this is an aspect of the Holocaust that is unique to the landscape. Maps and memories are germane to any microhistory of the region.26

1 A.J.P. Taylor, The Course of German History: A Survey of the Development of German History Since 1815, (London, 1961), p. 2.

2 Dan G. Cox and Thomas Bruscino (ed), Population-Centric Counterinsurgency: A False Idol? SAMS Monograph Series, CSIP, US Army CAC, (Kansas, 2011).

3 AŠarūnas Liekis, 1939: The Year That Changed Everything in Lithuania’s History, (Amsterdam, 2010), pp. 82–83; see also Norman Davies, Europe: A History, (London, 1996), p. 904.

4 Walter Frevert, ‘Zehn Jahre Jagdherr in Rominten’, Wild und Hund, (1943), pp. 148–153.

5 Robert T. Foley, Alfred von Schlieffen’s Military Writings, (London, 2003).

6 Discussions with archivists of the Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv. At the time of writing, there is uncertainty over the numbers of maps produced by the Wehrmacht.

7 Edward P.F Rose, Dierk Willig, ‘German Military Geologists and Geographers in World War II’, in Studies in Military Geography and Geology, 2004, pp. 199–214.

8 TNA, WO 208/3619, Interrogation Reports, CSDIC (UK), SIR 1706–1718, interrogation number 1709, German Army Warrant Officer Dr. Bartz 19 July 1945. He was described as a university geography lecturer, who returned to Germany after working in the USA and was conscripted into the army.

9 Sören Flachowsky und Holger Stoecker (Hg), Vom Amazona an die Ostfront. Der Expeditionsreisende und Geograph Otto Schulz-Kampfhenkel (1910–1989), (Köln, 2011).

10 Hermann Häusler, ‘Forschungsstaffel z.b.V. Eine Sondereinheit zur militärgeografischen Beurteilung des Geländes im 2. Weltkrieg.’ Schriftenreihe, MILGEO Institut für Militärisches Geowesen, Heft 21/2007.

11 Eric Hobsbawm, On History, (London, 1997), p. 201.

12 Anne Kelly Knowles, Tim Cole, Alberto Giordano (ed), Geographies of the Holocaust, (Bloomington, 2014). See also the essential secondary source was Ian N. Gregory and Paul S. Ell, Historical GIS: Technologies, Methodologies and Scholarship, (Cambridge, 2007); also, Anne Kelly Knowles (ed), Past Time, Past Place: GIS for History, (California, 2002).

13 Bettina Wunderling BSc. Geology (Göttingen), a certification in GIS (Kiel), and has studied at Aachen-RWTH. The GIS modelling was carried out with ARC GIS version 10.0 by ESRI Software.

14 Hein Klemann & Sergei Kudryashov, Occupied Economies: An Economic History of Nazi-Occupied Europe, 1939–1945, (London, 2012), plate 1.

15 This digital map represented the longest period of research and analysis prior to the full application of historical GIS.

16 Anne Kelly Knowles (ed), Past Time, Past Place: GIS for History, (Redland, 2002).

17 David Rumsey and Meredith Williams, ‘Historical Maps in GIS’, in Knowles (ed), ibid., pp. 1–18.

18 David W. Lowe, ‘Telling Civil War Battlefield Stories with GIS’, in Knowles (ed), ibid., pp. 51–63.

19 Ian N. Gregory and Paul S.Ell, Historical GIS: Technologies Methodologies and Scholarship, (Cambridge, 2007).

20 Geographisches Institut, Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, May 2009–March 2010.

21 Jonathan Raper, Multidimensional Geographic Information Science, (London, 2000).

22 Institute of Historical Research, Historical Mapping and GIS, (research training), May 2013.

23 Association of the US Army, Annual Conference, October 2006.

24 US Army Colonel Roger Cirillo, PhD retired supplied a copy: ‘Report of the Department of the Army Review of the Preliminary Investigations into the My Lai Incident’, Volume 1: Report of the Investigation, 14 March 1970.

25 Alberto Giodano and Anna Holian, ‘Retracing the “Hunt for Jews”: A Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Arrests during the Holocaust in Italy’, and Waitman Wade Beorn and Knowles, ‘Killing on the Ground and in the Mind’ in Knowles et al, Geographies of the Holocaust, (Bloomington, 2014).

26 For an example of this, see the travelogue in Omer Bartov, Erased.

1. The Ogre of Rominten

Knuff was a crafty and cuddly stag as his name implied, but he was elderly, and his days numbered. Although this mighty stag had large antlers he was reduced to the status of a commoner. There were too many weak points in his vital statistics that denied him a place in the regal stock book. Regardless of Knuff’s less than noble pedigree, Hermann Göring had honoured the beast by selecting him for his hunting record. In his last hours, Knuff led Göring on a merry dance across der Romintener Heide. Göring stalked the stag for a week but the ‘old gentleman’ simply refused to surrender. For only the briefest moments Knuff tantalisingly presented his flanks but never long enough to be shot. After five hours of fruitless stalking in the morning, Göring was resigned to failure and trundled off to breakfast. Just about to tuck into a hearty platter, the mighty hunter received a telephone call from a forester that Knuff had been sighted. Leaving his continental breakfast behind, he dashed off eager for the kill. Göring mounted a shooting stand, took aim, and with a masterful shot he killed Knuff. This was the supreme moment—the sublime one-shot kill, a ‘… staggering phenomena that successful fighter pilots are good shots’, wrote Göring’s biographer.1 While anecdote has shaped the myths about Göring, the tale of Knuff represents a narrative about the hunt and the Luftwaffe lost from history.

Hermann Göring is a complicated character, with a façade that is not always reflected in the literature. In the past, his biographers have been compelled to condemn rather than delve beyond the superficial. In this literature, Göring is painted as the Nazi archetype of failure. This notion is also reflected in the balance of books on the man: mostly about Göring and the Luftwaffe; a few books about Göring and the Nazi economy; and a handful of books about Göring and forestry. Consequently, we know more than we need to know about his failings with the Luftwaffe but know less than is necessary to fully comprehend his part in the Holocaust. These depictions do not give us a rounded view of Göring. For example, in 1945 when examined by allied psychiatrists, he was regarded as the most intelligent and unscrupulous of the Nazi war criminals held in the Nuremberg cells. In the courtroom, he rallied from apathy to become the last champion of Nazism and the guardian of his legacy. To start at the end, therefore, would inevitably lead to the conclusion that he was a deviant, unscrupulous, clever, dogged by physical issues, had an addiction to morphine, but ultimately cheated the hangman with suicide.2

Deep within Göring’s psychology, was a story of violence that began with hunting and continued through soldiering. As a child, he was taught to hunt by his Jewish godfather on palatial estates. Then he was removed from this opulent lifestyle at an impressionable age and sent to a military academy with its strict discipline. Göring became an army officer and was posted to a Bavarian regiment garrisoned in Mulhouse in the Alsace, an area annexed after the Franco-Prussian war 1870/1. Göring experienced occupation first hand. He served in the disputed frontier area and was present in the region during the political unrest that led to the Zabern Affair (1913).3 In 1914 he served in the trenches and later transferred to become a pilot. Göring was a fighter ace, served in and then commanded the famous Richthofen Circus and was awarded the Pour Le Mérite. Although Göring politicised his war record, it was not until he came to power that it became the central core of a radical political-military idea. In November 1918, Göring gave the farewell address as commanding officer of the Richthofen Circus, he recalled their combat victories and casualties. Fourteen years later, as President of the Reichstag, Göring recalled saying Germany would once again be allowed to fly, and ‘I would be the Scharnhorst of the German air force.’ Gerhard von Scharnhorst (1755–1813) was the driving force behind the reforms of the Prussian Army. An interesting role model since Scharnhorst was known to be, ‘silent and withdrawn, a man who looked more like a schoolteacher than an officer of the king.’ His ‘calm tenacity in adversity’ was in stark contrast with Göring’s temperament.4 When the Great War ended, Göring was at the peak of his physicality, a war hero with attitude, but unemployment forced him to search for direction—he met Hitler in 1922.

Göring’s Nazi biographer called him the ‘Führer’s paladin’ and pitched the narrative to his master’s achievements in rebuilding the nation. He had come a long way from his squalid street battles in Munich after the war. ‘From hero to zero’, in modern parlance informs a trajectory of violence that culminated in a bullet wound during Hitler’s Munich putsch (1923). The wound changed his physical being and the rest of his life. Göring saw himself as broken like Germany. His mission to create a Greater German Reich was as much a reflection of his condition as it was his endorsement of Hitler’s ambitions. Göring’s Nazism was different to that of Himmler, Rosenberg and Goebbels because it had been born in pre-war nationalism and fuelled by the events of 1918–1923. His belief in a Nazi military revolution was wholly different to both the SS and the army. His ideas were grounded in his self-constructed Germanic-romanticized-renaissance, bound by honour codes, Nazi etiquette, privilege and patronage. Richard Overy has argued that as the leading Nazi defendant at the Nuremburg war crimes, he bullied, chided and coaxed his fellow inmates. His inflated self-importance, egomania and ebullience left little room for contrition. In 1939 the allied politicians had believed Göring to be a moderate but at Nuremburg he proved to be as extreme as the rest of Hitler’s circle. Overy believed Göring was an old-fashioned nationalist with a radical personality.5 In 1933, as Prime Minister of Prussia, Göring enforced police regulations to smash Germany’s left-wing movement. From 1933, under his guidance, the forestry and hunting fraternities examined future legislation and regulations, which led to the National Hunting Law (1934) and the National Nature Law (1935). These ecological laws were subtle devices that conformed to the Nazi Volksgemeinschaft and the evolving police state. In March 1935, Hitler agreed to the formation of an independent Luftwaffe, within the Wehrmacht following rearmament, and Göring was made its supreme commander. The forestry service would incubate the birth of the Luftwaffe.

Göring’s Nazism was motivated towards restoring German national honour, but his institutional ambitions reached deeper into Third Reich society. Peter Uiberall was Göring’s official interpreter during the Nuremburg trial, and claimed the prosecutors were unable to reach deep inside Göring. Uiberall argued that confronting Göring with crimes committed in the name of Nazi Germany was pointless. He labelled Göring a ‘Condottieri type of personality’ who didn’t recognize right or wrong or know the difference between good and bad. As far as Göring was concerned the nation was an organism, a ‘body politic’ that had to be secured and protected by any means.6 Göring the Condottiero is an enduring image of corruption, Machiavellianism, and capriciousness. He was an enigma of countless variations. The political ambition, to make Germany great again—a political tract with remarkable durability—fused his ideas across the breadth of Nazi orthodoxy. Shaping a modern military institution out of forestry, hunting and aviation, which combined the elements that were most Germanic in spirit to raise a frontier police with the capability to strike at enemies from long distance. This was a breath-taking strategic concept even by Nazi standards. Frontier security reinforced with a hard punch was fundamentally defensive, but also colonialist and nation-building. The killing of Knuff, therefore, can be seen as symbolic of Göring’s representations of Germany—past, present and future.

I. The Green

The social engineering underpinning Göring’s organisational ambition was both racial and hierarchical. The green uniform of the state foresters and game wardens drew on the symbol of centuries-old traditions from German culture. There was a bizarre compromise between Hitler’s anti-blood sport rhetoric and Göring’s bloodthirsty passions. Their compromise settled on the institutionalisation of völkisch culture throughout the Germanic forest and Germanic game. On 3 July 1934, Göring introduced the Gesetz zur Überleitung des Forst- und Jagdwesens auf das Reich (the bill for the National Laws for the Centralisation of the forests and hunting).7 On 1 April 1935, the Reichsjagdgesetz (National Hunting Law) was enacted and the Jagdamt (hunting department) was established as a department within the RFA.8 Diagram 1 is an organisational chart of the Reichsforstamt, highlighting the Reichsjagdamt Abteilung IV. The diagram was drawn from the military plans for the forestry industry and the hunting fraternity for mobilisation into the Luftwaffe in the event of war. The national hunt law centralised management, regulated hunt discipline, incorporated the preference for Urwald or primaeval habitats and introduced a scheme for the advancement of the Germanic game. The politics of the hunt involved corralling the power and influence of the predominantly middle-class fraternity and propagating Nazi racism through the hunt’s classifying culture of social Darwinism.

[bad img format]

Diagram 1: Reichsforstamt organisation and the Jagdamt (1936).

Compiled from multiple sources filed under NARA, RG242, T77/100/145/301, (OKW WiRu Amt) Reichsforstmeister.

The German hunt was liberalised through laws made in 1848. The laws stimulated middle-class hunting, a social-cultural phenomenon in Germany. This process of culturalization was accelerated by industrial innovation in advanced gun design and manufacturing, mass-produced accoutrements and the mass distribution of cheap popular hunt literature.9 During the Great War, hunting became a symbol of the inherent warrior masculinity of German soldiers. The collapse of monarchy caused an ideological void within the hierarchy of the hunt regardless of the increasing influence of the middle-class. The middle-class hunt was bereft of ideology because of the preponderance of a modus operandi steeped in professionalism. There was a great outpouring of hunt literature after 1848, but there had been no single volume codifying a general hunt etiquette until 1914.10 Raesfeld’s hunting manual was written from a professional standpoint and became the standard reference because he avoided dogma and didn’t offend anyone. Fritz Röhrig, a senior forester on the staff of Greifswald University, later published a cultural history of German hunting with an undisguised national-conservative bias.11 Like most from his profession, the first edition condemned völkisch myths of the Germanen tribes, Germania and the growing desire for ritual from within the hunt. A later edition incorporated a nuanced Nazi narrative. He argued the period immediately after 1848 had led to the endangerment of game, especially the extensive killing of elk, deer and beaver. This was coded language for maligning the middle-class as ‘trophy vultures’. Röhrig however, was hostile towards both dominant social groups of the hunt. He criticised the ‘privileged classes’ (aristocracy) for their irresponsibility in opening the estates to “guest-hunters”. He railed against the middle-class for transforming the hunt into a shooting exercise. The local shooting clubs and rifle associations were also a target of his ire. Röhrig claimed the hunt declined after 1919 partly caused by the alienation of the Jagdjunker (hunting aristocrats) and the vilification of foresters as royalist lackeys. Thus, between Raesfeld and Röhrig, there had been an observable politicisation of the hunt.

Röhrig’s ideological resentment was vented against the Communists with the accusation that they had machine-gunned game as symbols of capitalism. He attacked the societal craze for money where profiteering proliferated and endangered the lives of foresters with a sharp increase in murders. There had been an increase in poaching, and he blamed the complicity of ‘unsavoury characters’ like the Salonjäger (saloon hunters), Schiesser (shooters) or Fleischmacher (meat-makers). Röhrig criticised the ‘red’ press, satirical newspapers and Artfremde (aliens) for lampooning the hunt with cheap and vile satire. He generalised that all postwar periods, throughout history, were disastrous for hunting because unemployed former soldiers turned to poaching and banditry. Poachers had never been tolerated by the hunt. If arrested, the punishments were severe with the loss of an eye or hand, or public execution. His chapters took a racial dimension when he described how Hessen had regulated against Jewish traders by making them swear an oath to report any illegal trade in furs. In Prussia, Jewish traders were forced to purchase certificates to trade furs.12 Röhrig accused Weimar politicians of hypocrisy, patronising the hunt’s feudalism and participating in private hunts, but ridiculing the hunt in parliament. The rising values of wood, forced Weimar governments to improve the lot of state foresters. This brought about improved training and schooling, but the social emphasis had shifted away from the hunt. The decline in the domestic game forced hunters to seek alternatives overseas, in safaris and hunting dangerous game in primaeval habitats.13 Writing after the Nazis were in power, Röhrig congratulated Hitler. He was grateful for the eradication of the “red” menace. The Nazis were the saviours of Germany and Göring had protected both the forest and game. Röhrig called Göring’s 1935 hunting law a “monument in his own lifetime” widening the national and classless appeal of the hunt and realising the goal of harmony with the Volksgemeinschaft.14

Göring as chief of forestry and master of the hunt was responsible for an institution of diverse talents. The first Generalforstmeister of the Reichsforstamt (RFA) was Dr. Walter von Keudell (1884–1973), a long serving Prussian civil servant. He was removed from office in 1937 because he refused to implement Göring’s policy for cutting quotas. He was replaced by Friedrich Alpers (1901–1944), who had studied law at Heidelberg University and became a committed Nazi in 1929. Alpers took an honorary SS officer rank and in 1941 worked on the infamous hunger plan that led to the starvation of millions of people in the east. The Jagdamt (the hunt bureau) was organised as a department within the RFA. The chief of the Jagdamt was Oberjägermeister Ulrich Scherping (1889–1958) who was accountable to Keudell and later Alpers, but in practice reported directly to Göring. Scherping was the architect behind the hunting law and was deeply committed to the process of Nazification. He was born in Pomerania and began a career in the army as a cavalry officer, and like Göring was an early devotee of hunting. During the Great War, his bravery was rewarded and was promoted to the general staff of an infantry division. In August 1915, Scherping arrived in Białowieźa and was left awestruck at the magnitude of the forest. After the war, he joined Freikorps Rossbach at the same time as Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s first deputy.15 Scherping took up a career as a professional hunter and a staff writer for Der Heger (a hunt journal). In 1927, he became general manager of the Deutsche Jagdkammer (German Chamber of Hunting) an organization founded in 1920 and a year later the Reichsjagdbund (National Hunting Union). He gained a reputation as the hunt’s leading political activist and the exponent of right-wing dogma. In 1934 he acquired the title Oberstjägermeister (Colonel of the Hunt) and became Ministerial director of the Jagdamt. The adoption of Oberstjägermeister with its royalist resonance, a rank placed seventh in importance among the two thousand positions in the Kaiser’s royal household, made him a target for lampooning from Nazi rivals of which there were many.16 Scherping clung to Göring in all matters of policy, politics and rivalries, but was astute enough to cosy up to Himmler and serve on his SS personal staff.17