Birds of Prey

Aldo Leopold, the American naturalist, visited Germany in 1935. He made observations of Göring’s reforms at work and visited Silesia to meet Günther-Hubertus Freiherr von Reibnitz, the Gaujägermeister or Regional Director, with his assistants the Kreisjägermeisters. The meeting was held in a local police station where Reibnitz’s offices were located, which reflected the future of German forestry and the Nazi police state, but Leopold did not report on anti-Semitism.18 Scherping was responsible for the Aryanisation of the hunt. In 1935 the hunt acquired self-policing powers that allowed the implementation of an Aryanised membership base. In 1937 he announced, ‘the hunt had become a closed shop to outsiders and had restored its noble reputation’, and then added that ‘the law had removed anti-social elements that gave hunters a bad name’—he meant the Jews.19 Rules were drafted to define those persons excluded from the hunt as ‘foreigners without German nationality’, which also meant Jews.20 In The Nazi Seizure of Power, Allen discovered that all the local shooting associations were quick to discriminate against Jews, cancelling their memberships once the Nazis came to power.21 Then Nazi hatred for the Jews exploded into violence on 9–10 November 1938, during Reichskristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass), which led to the arrest of more than 30,000 Jews and more than ninety killed. A few days after the violence subsided Göring hosted a conference of state officials at the Reich Air Ministry. He joked the ‘Jews could be restricted to forest areas inhabited by elk, which, like Jews, were marked by their large, crooked noses.’22 The tragic culmination of Nazi race policies was the assistance given by the RFA in East Prussia to supply timber for the construction of the Stutthof concentration camp in 1941.23

Long before the Nazis came to power, the hunt had departed from the natural science classifications of the renaissance to the rigid social Darwinism of the Nineteenth Century.24 In post-colonial Weimar Germany, the hunt spun fantastical and exotic accounts of the ancient and extinct game. Under the Nazis, the recreation of the Germanic game became part of a racialised zoology, game and habitat research. The science of hunting began to follow many research trajectories. In 1936 Göring founded an institute of hunting science in Hannover, which later transferred to the University of Göttingen. The Heck brothers, Lutz (1892–1983), and Heinz (1894–1982) had also been experimenting with their breeding back programme to restore the long-extinct Aurochs. Their work involved the mass observation of European cattle breeds to isolate what they believed was the special characteristics of the Aurochs. The first breeding experiments led to a breakthrough in 1934 when they sired a bull later called ‘Heck cattle’. Lutz declared the research funded by Göring was the greatest value to science and a ‘the symbol of German power and courage.’ From 1938 Rominten’s game population was re-engineered. Wild boar and five Heck Cattle were released under Göring’s orders. Eventually, five lynxes were released, the precise number recommended for game management purposes.25 Leopold described the prevailing conditions of the hunt in Germany, ‘Every acre of forestland in Germany, whether state or privately owned, is cropped for game.’26 He blamed this on the German obsession for hunting deer, which outweighed the damage herds caused the habitat. He believed there would be long-term consequences, especially among game birds. He was deeply critical of foresters who ‘sprinkled’ hardwood trees among pine forests to achieve mixed forests but were unable to create a balance in-game management.27 Leopold and other foreign either overlooked or ignored the prevailing Nazi racialism—both the game stock and the people were being Aryanised.

The long-term implications of decisions to the national ecology were a constant theme of discussion. Leopold learned of the German appreciation for predators in preventing the degeneration of game, and the status of the wolf as the noble animal of the wilderness. Decades later he claimed this idea for himself.28 However, not all predators and aggressive game were appreciated. A postwar rumour circulated that Göring had a morbid fear of snakes. His senior hunter disclosed this secret to explain Göring’s absence from hunting in wild forests and his preference for high stands. During a visit to Darss, a nature protection park, Göring was shocked and petrified to learn it was the habitat for poisonous Adders. An unnamed forester informed Göring that hedgehogs killed snakes. He immediately called Lutz Heck and ordered 300 hedgehogs brought to Darss. He was persuaded there was no veracity in the story that hedgehogs killed snakes. Göring immediately departed from Darss never to return.29 If Göring had a morbid fear of snakes, it represents an important insight about his fears, but also points to his enthusiasm for eradicating all Jews as vermin.

In 1938 Lutz Heck was promoted chief of nature protection and natural monuments within the RFA.30 He set about a building programme of national parks and game reservations. Heck wanted the people to observe native animals and the habitat to comprehend how the Nazi culture social Darwinism functioned to the greater benefit of German society. Mass public education through micro-models of game habitats was conceived as a means to concentrate the people’s ‘organic gaze’ on the biological values of everyday existence. These early forms of bio-zone were predicted to elevate social Darwinism as the normal natural order of life. Heck believed he was fulfilling the national will because Hitler’s genius was his understanding of nature and its centrality to nation-building. The national parks were put to service in the Nazis’ policies for national recovery.31 The ambition to restore the Germanic game was the mirror of the Aryan being. The Aryan man and Germanic game co-existed in the timeless myth of antiquity. Heck’s ambitions were not limited to Göring, he accepted honorary membership to the SS (June 1933) unusually before joining the Nazi Party (May 1937). He served Himmler’s SS-Ahnenerbe (society for Ancestral heritage) founded in 1935. This SS institute advanced research into racial theories and championed Aryan primacy. Among this group of Nazis, the plans for Białowieźa were conceived.

The ideological lynchpin necessary to complete Göring’s corporatism and institutionalisation was some form of honour code. In 1936 Scherping, under Göring’s orders, instructed Walter Frevert (1897–1962) a state forester and hunter, to write a book about Nazi-German hunting customs. The Jagdliches Brauchtum (1936) drowned the reader in völkisch claptrap but proved to be an instant political and public success. Scherping’s foreword to the book was opaque, ‘The German people are grateful to the Führer for restoring and awakening old and beautiful customs.’ The success of the book led to Frevert’s elevation to Göring’s inner circle and later as a Leibjäger, a personal hunter and confidante, an important position in the hunt hierarchy. Frevert was born in Hamm (Westphalia), his father was a dentist; but, after a distinguished war record as a young volunteer, and a period in the Freikorps, he chose to become a state forester specialising in the hunt. His first forestry rank was Forstassessor and was promoted in 1928 to Forstmeister while serving in Battenberg. Frevert had joined veterans’ associations but in May 1933 became a member of the Nazi Party, and in the summer joined the SA. Frevert’s Nazi membership initially looked like career opportunism, but his subsequent behaviour singled him out as a racist zealot.32

The Jagdliches Brauchtum was an orchestrated departure from the traditions set down by Ferdinand von Raesfeld in 1914. Frevert dispensed with historical accuracy, ignored quips about pompous hunters, and revelled in any applicable German sources. He adapted a poem by Ernest de Bunsen (1819–1903) to express his sentimentality of the hunt: ‘The origin of the hunter is in the long past close to paradise. There were no trade people, no soldiers, no doctors, no priests, no lawyers but there were already hunters.’33 However, a serious shortfall in sources about German hunt customs and even fewer German methods led him to invent material for his book. The final version of Jagdliches Brauchtum was a Nazi fantasy composed of made-up stories, plagiarised ideas and foreign rituals. He confessed his reasons were for a good cause, but nobody cared because the book met the approval of all things völkisch prevailing at the time.34

The climax of the inventions was the Bruchzeichen, a centrepiece of ritual and a ceremony of ‘breaking’ the dead game. Once the animal was killed and retrieved, the Bruch was started. The ceremony opened with a tune from a hunting horn to the dead animal. The hunter then placed a sprig in the animal’s mouth representing its Letzter Bissen (the last meal). The sprigs were taken from oak, spruce, fir, alder or pine trees. The hunter then placed a sprig over the beast’s heart and another covering its nether regions. The hunter’s companion then dipped a sprig of leaves into the animal’s blood, drew his dagger with his left hand, placed the sprig on the blade, and presented it to the hunter. The hunter then took the sprig with his left hand, uttered the words Weidmann’s Dank (the hunter’s thanks), and fixed the blood-soaked sprig to the left side of his hat. If a bloodhound had participated in the kill, it also received a twig placed in its collar. Once the first part of the ceremony was completed the hunter opened up the carcass and removed the entrails.

Image 1: left to right, Oberforstmeister Walter Frevert Rominten, Göring in his capacity as Reichsjägermeister and Oberstjägermeister Ulrich Scherping.

Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1979-145-13A / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Image 2: Senior Luftwaffe and state foresters in the lounge area in Rominten. A painting of a European Bison is hung on the far wall.

Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1979-144-15A / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Image 3: European Bison in Białowieźa.

Source: Author, 2009.

Once completed, the hunter began the Totenwacht (guard the dead), an hour-long vigil over the carcass. During this hour the hunter was expected to reflect on the sublime kill and recall past hunts with all their joys and miseries. The carcass was then included in the total tally for the final rituals. The dead carcasses were arranged in order of nobility, size, and by rank, like soldiers on a parade ground. If it was a large tally, braziers and flaming torches were added to the ambience of the moment. The results of the day’s hunt were then read aloud. The horns sounded several more tunes, announcing the end of the hunt at which point the hunters and their guests would raise their right arms in the Hitler Gruss (Nazi salute). Then followed the final horn sounding the Halali (tally-ho). After the ceremonies were over the hunters retired to the dining room to partake in the Tot-trinken (toast to the kill). The antlers were placed on tables, with candles and more sprigs added for decoration. Dinner was then served by silver service.35

Deconstructing Frevert’s invention is not difficult. David Dalby has explained the Bruchzeichen was a French ceremony. He claimed when German nobles were offered the ritual in the Middle Ages, they expressed no interest.36 The Letzter Bissen originated in James Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1922), which was conveniently published in German in translation in 1928.37 Frevert’s justification, was the Totenwacht had increasingly appealed to hunters in the two decades since circa 1916. This had associations with the widespread death cults and ceremonies that emerged during the Great War. Frevert confessed two music scores were composed for the book by Professor Cleving (Berlin). They were the Muffel tot and the Halali.38 Gritzbach, Göring’s Nazi biographer, claimed the Jagdliches Brauchtum restored the ‘heroic realism’ and traditions of the past. He enthused over the combination of faith in Urwald (primaeval wilderness) and its relationship to Germanic hunting customs. He believed Frevert’s efforts would form the common etiquette for all German hunters.39 The institutionalisation of the Jagdliches Brauchtum brought uniformity, while the reinvention of customs and traditions helped assimilate Nazi ritualism within the hunt. Ceremonies were devised that honoured the dead and invoked pagan pre-Christian style rituals that had never been associated with German hunt lore.40 The death ceremony was an invention and few in history have been quite so blatant. This bizarre story of the invention, however, found its way into Nazi ceremonies and rituals that preceded the Holocaust. To paraphrase Hobsbawm, ‘nothing appears more ancient, and linked with an immemorial past than the customs’ of the German hunt. In 1970 the German hunt handbook still referred to the ideas of Oberforstmeister Frevert and Scherping.41 Hosbawm opined that customs are not a brake on innovation and precedent can be changed when appearing to bring about ‘social continuity and natural law’.42 Like Faust, Frevert had made a pact with the devil.

II. The Blue

The Luftwaffe uniform colour was blue-grey. The colour selection was to distinguish the Luftwaffe uniform from the grey-green of the army and Kriegsmarine. ‘The Blue’, unlike state forestry was a ‘new’ Nazi elite. From the outset it was as an institution burdened with internal tensions and riddled with mediocre leadership. A postwar narrative of Luftwaffe history was manufactured by Adolf Galland’s based upon his memories and fantasies. In The First and the Last (1950) Galland effectively rganizatio his political involvement in the Nazi state. He acknowledged Göring as the founder of the Luftwaffe, but was reluctant to discuss the deeper Nazi pedigree. He also recognised that Göring had allocated forty per cent of total rearmament costs to the Luftwaffe, while he was responsible for the Third Reich’s economy.43 His most serious criticism was also toward Göring, as ‘supreme commander’, for surrounding himself with his Great War cronies. Galland claimed they shared a common failing of not understanding modern aviation.44 Where Galland was less forthcoming was how the Luftwaffe had been incubated through the RFA’s paramilitary structure. The Luftwaffe’s rganization, air bases, depots, manpower, structure and ideology were acquired from RFA resources. Galland dropped a hint of this relationship in reference to the Elchwald estate that served as the headquarters for his command. Göring turned over his palatial lodges into Luftwaffe headquarters for the duration of the war. The RFA facilitated the rapid rganization of the Luftwaffe across the estates and bases in East Prussia.

The reasons for Galland’s myth-making are not difficult to deconstruct. Stephan Bungay argued the Luftwaffe was as much political as it was a military rganization.45 He pointed to the Göring and Ernst Udet (1896–1941) relationship, as the champions of the warrior-hero ethos. They introduced the notion of ‘romantic amateurism’ as the ideological glue of the officer corps. Bungay believed this stunted the Luftwaffe’s military development. The Luftwaffe had been raised from a broad cross-section of the population, unlike the army it was recruited nationally rather by state like the army.46 Bungay focusing aircrew noted that by 1939 the officer corps had reached 15,000 comprising of pilots, army officers, and the technical services. In basic training, the Luftwaffe instilled an attitude of common experience and service. During the Spanish Civil War, according to Bungay, the German aces became poisoned by ‘romantic amateurism’. Galland was a typical example of this clique. He was known to have recommended the removal of radios as unnecessary in the cockpit of fighting aeroplanes, in a dubious challenge to modernity.47 Bungay was deeply critical of Göring, Udet, Galland and others but blamed this on traits of the ‘Herrenvolk’ and the temporary loyalty of the pack that followed whoever was leader.48 There was a persuasive argument but not entirely accurate and misunderstood the nature of Nazism. The deteriorating fortunes of war encouraged a rise in the cliques but their loyalty to Hitler never waivered.

Image 4: Reichsmarschall Göring, Lw.Generalmajor Adolf Galland, Lw.Generaloberst Bruno Loerzer and Reichminister Albert Speer, August 1943.

Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J15189 / Lange, Eitel / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Göring’s military ambitions for the Luftwaffe was more sophisticated and corporate than Bungay could imagine. There are signposting clues in the literature and archives. In the foreword to the 1933 edition of Richthofen’s biography Göring wrote, ‘I was honoured by the confidence shown in me when I was appointed the last commander of the Jagdgeschwader Richthofen. This appointment has bound me forever and I will carry this responsibility in the spirit of Richthofen.’49 During a meeting in 1944, Lw.General of Paratroops Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke confronted Göring over the command of the airborne formations. The reply was unexpected. Göring explained why they must remain under his command: ‘I’m glad that I have them under my own wing in the Luftwaffe so that they are steeped in the spirit of the Luftwaffe … it’s the spirit that counts. In the same way … the French revolutionary army … in Paris simply swept away all the old French guards who’d had years of training.’50 In allied captivity, in 1945, Galland testified to British interrogators that Göring told him in early 1941, ‘In a few months we shall attack Russia … the whole affair was meant to last ten weeks at the most. After that the army was to be reduced to sixty ‘Divisonen[sic]’. But they were to be elite troops to hold the west, and the remainder of the ‘Divisionen’[sic] so released would be used for building an Air Force. Everything was to be put in the Air Force. That was the Führer’s plan.’51 These three anecdotes reveal something about Göring’s concepts of leadership, rganization and fantasies.

The subject of leadership has always raised questions about Göring’s ability. His senior Luftwaffe adjutants were known colloquially as the ‘small general staff’. The most significant member of this clique was Lw.Colonel Bernd von Brauchitsch, nephew of Colonel-General von Brauchitsch, chief of the army until 1941.52 There was no official job description for his post, but under cross-examination before the Nuremburg tribunal, in March 1946, Brauchitsch explained:

I was the first military adjutant of the Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe. I held the rank of chief adjutant. I had the job of making the daily arrangements as ordered by the Commander-in-Chief and working out the adjutants’ duty roster. The military position had to be reported daily; military reports and messages only to the extent that they were not communicated by the offices themselves. I had no command function.53

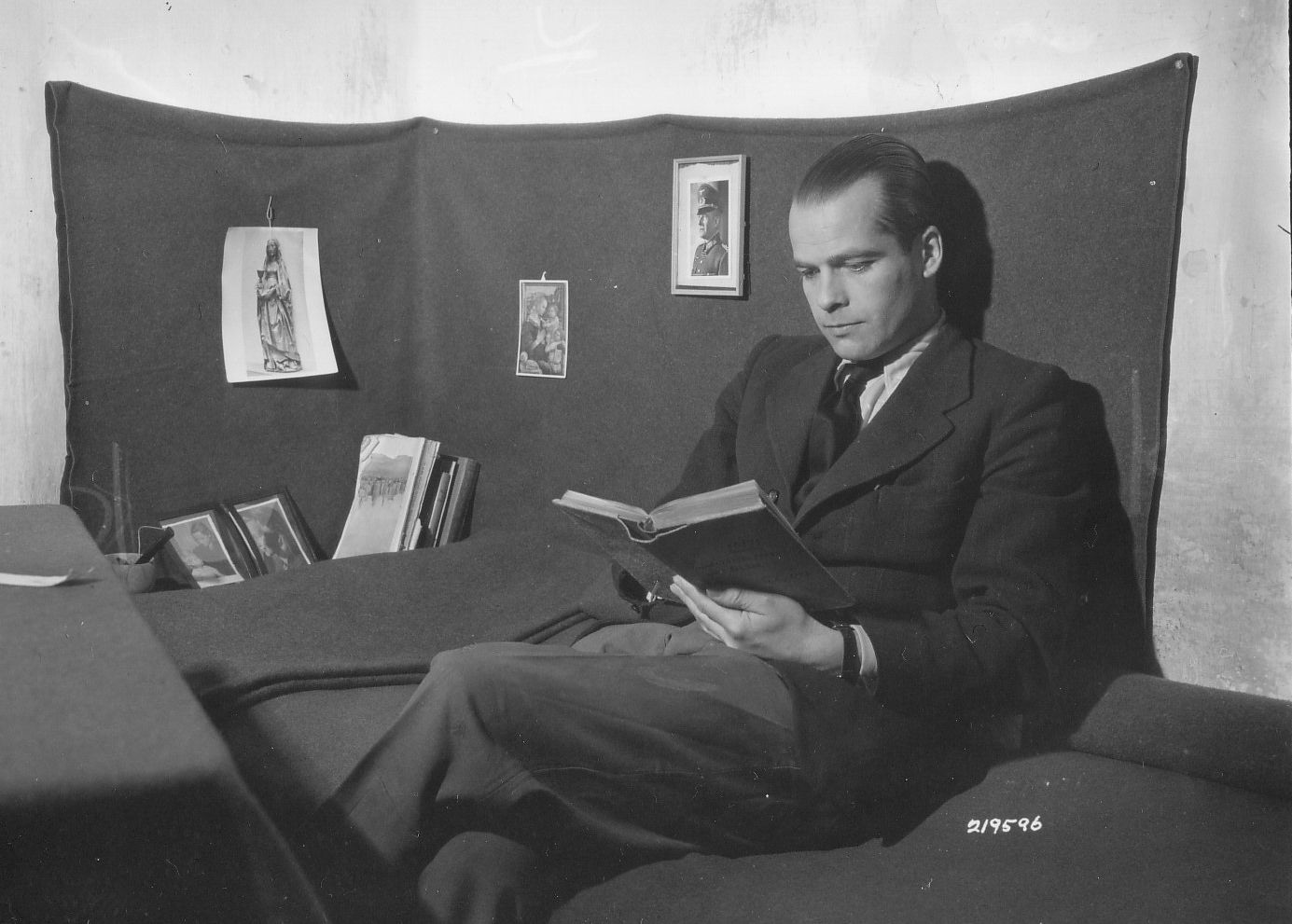

Brauchitsch’s importance to Białowieźa was his role as an intermediary forwarding Göring’s orders to the battalion(s) and in return collating their regular reports. Galland offered his allied interrogators an abrasive opinion of Brauchitsch. On 16 May 1945 he said:

Brauchitsch has been with him [Göring] for four or five years and he had a very bad influence, in that he always concerned himself with politics and didn’t hold himself aloof; as a chief ‘Adjutant’ he should have—the varying information should be condensed, but not selected.54

Image 5: Bernd von Brauchitsch in his cell in Nuremberg prison 1946.

Source: NARA, Hoffmann Collection.

Setting aside Galland’s dislike of Brauchitsch, the evaluation that he was inclined to side with decisions and sift reports was not unusual in Göring’s world. Galland of course was an integral member of the same command structure and his reputation was never really tested over his influence on shaping the fighter command. However, what can be drawn from the observations by the senior echelons of the Luftwaffe was the absence of ‘band of brothers’ style fraternity.

The RFA/Luftwaffe rganization documentation highlights an intensive period of planning around 1935–7 and subsequent annual updates. Evidence of this rganization planning can be found in other scholarship.55 From 1935 apprentice foresters and gamekeepers were required to serve for one year in the army (later the Luftwaffe) before becoming foresters. Older candidates were expected to participate in a three-month military refresher course alongside other Nazi officials.56 Michael Imort has argued this, ‘was all it took to rganization the forest service.’ The Luftwaffe’s rganization and peacetime expansion was based upon a general rganization calendar drawn up by the RFA in the mid-1930s and continually updated to 1940.57 Göring was determined to set in motion plans for the rganization of the Reichsforstbeamte (RFA’s public servants) including all members of the hunt offices to the Luftwaffe. This process behind a rganization calendar issued precise instructions for the transfer of all forestry officials to the Luftwaffe command structure. In 1936 forestry manpower numbered 870,000, and even by 1945 although greatly depleted forestry could still supply conscripts under the general Wehrmacht reserve assessment.58 The RFA’s rganization in the event of war was bound to the Wehrwirtschaftstab (economic warfare staff) of the Luftwaffe with wood and timber both regarded as strategic raw materials. During the war, forestry manpower was rganizat through the Luftwaffe although foresters served in specialist forestry units of the army, navy and Waffen-SS.59 Further evidence of rganizationn rganizationn can be found in the blue-grey uniforms with green insignia that recognised foresters serving in the Luftwaffe.60 From very early on the Luftwaffe was imbued with National Socialist spirit and by August 1944 it numbered between 2.8 and 5 million men, women and youths depending upon on which authority. The largest number of troops were in the ground forces and, in terms of manpower alone, the Luftwaffe constitutes a significant historical entity.61

In meeting Hitler’s expectations, the Luftwaffe departed from the traditional military formation, incorporating the dogma behind ideological warriors. The roots of this rganizationn began in 1929 when Göring informed the Reichstag of the inevitability of a future German air force.62 Once in power, Göring’s first priority was to consolidate political power. As Minister-President of Prussia, Göring ordered the raising of reserve police and volunteer paramilitary units. They combined his military expertise, with paramilitary policing methods, in security actions to crush left-wing political parties and communists. The police flying squad (Polizeiabteilung z.b.v. Wecke), named after its commander was mustered on 23 February 1933, with a force of 14 officers and 400 men. This formation was garrisoned in the Friesenkaserne, in Berlin, and became ‘godfather’ to the first SS detachments sealing that special relationship between the SS, police, and the Luftwaffe.63 Wecke’s first police actions were on 2 March 1933, rounding up communists and Marxists in Berlin. In 1936 this unit was turned into Prussian police regiment General Göring and was then transferred to the Luftwaffe to form a bodyguard. By 1944, this bodyguard had transformed from a regiment to the panzer division Hermann Göring, and by the war’s end was designated an airborne-panzer-corps.64

The social appeal of Luftwaffe recruitment was the proximity to advanced technology, aviation and the sense of speed. Compared to the SS, the Luftwaffe represented a larger and more interesting option for the nobility deeply bound by its class, its racism and elitism. Under Göring’s leadership flying, hunting and highbrow rganizatio offered an extension of the prestige, privilege and stimulus they were socially accustomed to. The list of nobles that joined the Luftwaffe included: Philipp Landgrave of Hesse (Nazi party member 1930), Nikolaus von Below (Hitler’s Luftwaffe adjutant), Günther Freiher von Maltzhahn (fighter ace and senior officer), Wolfram Freiher von Richthofen (cousin of Manfred, senior field commander), Heinrich Prinz zu Sayn-Wittgenstein and Egmont Prinz zur Lippe-Weissenfeld (both night fighter aces) and Hans Graf von Sponeck (airborne forces commander). However, like the German hunt, the majority of would-be flyers hailed from the middle-class with strong social values that were based upon professionalism, technocracy and innovation. Even working-class boys saw advantages of technical training and apprenticeship that offered greater opportunities for career advancement.