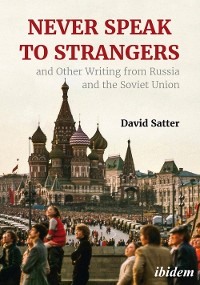

Never Speak to Strangers and Other Writing from Russia and the Soviet Union

The Soviet dissident movement appeared in its present form in the late 1960s and has suffered repeated repressions since then. But never before has it lost so many of its key personalities in such a short time. Dr. Sakharov is now almost the only major dissident still active in Moscow and the absence of other well-known personalities such as Dr. Orlov, Mr. Ginzburg, and in a few days, Gen. Grigorenko, removes men whose wide contacts made them invaluable sources of information about human rights abuses throughout the Soviet Union.

The tactics being used against the dissidents are sometimes brutal. But, as a rule the KGB attempts to suppress dissent with a minimum of violence. This can be done by arresting some people, allowing many others to emigrate and making the choice between emigration and arrest almost a matter of whim. Dissidents speak of the “black box” which contains their fate. It is impossible to say with certainty, for example, why Anatoly Shcharansky was arrested and faces treason charges while Dr. Turchin, who succeeded him as the principal dissident spokesman, was allowed to emigrate to the U.S. The inability of the individual to predict the reactions of the KGB, predisposes him toward restraint.

The disorganised state of the dissident movement today comes as a particular irony since it was the 1975 Helsinki agreements with their clear pledges to respect human rights and facilitate the free flow of information which last year gave the movement new life. The Soviet Union is anxious to sign human rights commitments in keeping with its world stature but, for internal reasons, reluctant to honour them. The dissident Helsinki monitoring group, which was founded by veteran dissidents last year, for the first time managed to unite all the principal strands of Soviet dissent—the democratic movement, the Jewish emigration movement, the religious rights movement—into an organisation dedicated to taking the Soviet Union at its liberal word. From the Soviet point of view, the group probably had to be repressed to ward off independent pressure on the Soviet Government to honour its international commitments emanating from within the country.

The dissident, movement may enter a period of relative inactivity in the months ahead. The Helsinki group in Moscow it still functioning but has only four members and there is widespread apprehension about the expected trials of Dr. Orlov, Mr. Ginzburg and Mr. Shcharansky.

The forces which produce new dissidents, however, continue to operate. Sergei Polikanov, a nuclear physicist and corresponding member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences held a Press conference recently to protest the refusal of the authorities to allow his family to accompany him for a year of research at a nuclear laboratory in Geneva. By speaking out against the kind of harassment to which almost all Soviet scientists are subjected, Professor Polikanov put his career at risk and took the first step toward one day joining the ranks of those active dissidents whose numbers in Moscow are so depleted now.

Financial Times, Thursday, December 8, 1977

Soviet intellectuals are not the only ones being hounded

Trials of the Workers

“We are a vast army of Soviet unemployed, thrown out of the gates of Soviet enterprises for attempting to exercise the right to complain, the right to criticise, the right to freedom of speech.”

So begins an open letter by 72 working people from 42 cities who lost their jobs for protesting against bad working conditions and corruption. The letter and the testimony of several representatives of the group in Moscow cast doubt on the view that, although ideological criticism is barred in the Soviet Union, it is possible for the individual worker to voice objections to specific industrial practices.

“We undertook to offer publicly,” the open letter said, “critical remarks against the plundering of socialist property, bad conditions of work, low pay, high injury rates, the raising of production norms leading to waste and low quality production.”

Seven representatives of the signatories recently met with foreign correspondents in an apartment in a new district on the outskirts of Moscow where they described their personal experiences. They insisted they are not “dissidents” but rather working people concerned to correct specific injustices. They supplemented their personal stories with documentation of other cases and copies of appeals to State and party organisations, as well as a second letter, protesting recent repression against complainants, addressed to the Soviet Press.

The working people at the Moscow meeting said the 72 signatories met each other while seeking hearings for their individual complaints in the reception hall of the Soviet Procurator, the Communist Party central committee, and the Supreme Soviet, the Soviet Parliament. These halls are the scenes of considerable tension because, according to the letter to the Soviet Press, “it is difficult to foresee in advance who among those waiting will be seized” and taken to the militia station, or for a “conversation” with the admitting doctor at a mental hospital.

The workers said they began to organise their efforts after discussion in the crowded halls convinced those present that their similar individual problems had more than a “private character.” The following cases, related to correspondents by workers present at the recent meeting and taken from the documents the workers’ group provided, cannot be verified under Soviet conditions. The signers, however, took a considerable risk by making them public and insist they are representative of the fate of thousands of individuals in the USSR who openly challenge industrial abuses.

Vladimir Klebanov (45), of Makeevka in the Donetsk industrial district, told correspondents that he worked in the Bazhanova coal mine for 16 years. He became concerned about excessive overtime at plan fulfilment time which frequently meant that men worked 12 hours a day instead of the standard six-hour coal miner’s shift, contributing to between 12 and 15 deaths and 700 injuries a year, which, he said, was considered “normal.”

Mr. Klebanov said that in 1968, after he became a shift foreman, he refused to require overtime of his men or to send them into the mine when safety equipment was missing or broken. He was charged with slandering the State and committed to a mental hospital.

Mr. Klebanov is the leader and principal organiser of the “worker-dissidents” and the documents he and others distributed at the meeting described industrial abuses that, in the West, would have been combated by a labour union.

These included the cases of Natalia Matyusheva, who worked as a hostess in a pension in Gorki and was sacked for “truancy” after protesting publicly about the death of a motorist which she said was the fault of the resort doctor, and Maria Melenteva, who lost her job for seeking a pension after 27 years of arduous labour.

Soviet unions exist on a per industry basis but they are run by the Communist Party which arranges the appointment or election of officials. These officials arrange special services such as paid holidays, but also aid management in meeting production quotas and maintaining discipline. The victims of industrial abuses appear to have no recourse.

Anatoli Poznyakov (39), worked as a locksmith for Roubles 75 (£58) a month. He told correspondents at the meeting that when he asked for a rise, he was insulted and after appealing to the local party organisation, told that his destiny in life was “to eat from a pig’s trough.” Further appeals led to his dismissal and he now lives on a semi-disability pension of Roubles 21 a month (he is an epileptic) and his mother’s pension of Roubles 45 a month.

Nedzhda Kurakin told correspondents she had worked for 25 years in a “closed restaurant in Volgograd.” She said restaurant managers were docking her pay and that of other waitresses for fictitious broken crockery and then ordering new crockery for themselves. In 1975, she made these charges at a party meeting and was fired for shirking. She said the Volgograd party leader she had known for 20 years refused to see her and she has been unable to find a job since.

Many of the industrial grievances described to correspondents or mentioned in the documents, like that of Mrs. Kurakin, concerned cases of organised corruption or theft, known to be serious and a growing problem for Soviet industry. Even in such cases, however, the response of Soviet institutions, including legal institutions, appeared to be instinctive support for existing authority.

Valentin Poplavsky (44), formerly head of the maintenance department for company housing at a factory in Klimovsk outside Moscow, said he was sacked after refusing to write a reprimand into the work record of a woman who protested about the use of company funds for drinking parties. To silence his vehement protests against the firing, he said the militia, acting on his ex-director’s instructions, entered his apartment and beat him in front of his wife, children, and 97-year-old father. When he tried to file a complaint at the prosecutor’s office, he was given a 15-day jail sentence and shortly afterward, his wife was fired from the job she held for 18 years.

The worker dissidents said in their open letter that they do not have philosophical objections to the Soviet system but simply wants its constitutional guarantees, such as the right to lodge complaints and the right to protection by the courts, to be honoured in practice.

Financial Times, Friday, May 19, 1978

Yuri Orlov’s Trial

The Price of Calling the Helsinki Bluff

The crowd outside the courtroom where Dr Yuri Orlov1 was being tried provided an uneasy audience for an animated debate between a dissident and a clean cut young man who was defending the Soviet system.

The argument ranged over the material situation of Soviet citizens and conflicting claims about freedom in the Soviet Union, and finally came down to the question of why close friends of Dr. Orlov were being barred from his trial.

“Who said that you are barred from the trial?” said the clean-cut young man. “I’ll go over there and get in now,” he added and began striding purposefully toward the iron barricades and crowd of militia men barring the entrance to the courtroom.

At the barricade, he was overheard by a Western correspondent to ask the police “what do I tell them? They want to know why they can’t get into the court.” One of the police, apparently taken aback by his co-worker’s stupidity, told him, “Tell them the hall is full.”

That was how it was during the four-day vigil on the sidewalk outside the “open” trial of Dr. Orlov. The testimony came from prosecution witnesses; the audience, with the exception of Dr. Orlov’s wife, Irina, came from the ranks of the country’s “enthusiasts”; and the honest workers who mingled menacingly with dissidents and journalists were provided by the police.

At the weary Press conference with Mrs. Orlova following the announcement of the sentence, Mr. Vladimir Slepak, a Helsinki group member who has been trying to emigrate to Israel for nine years, said: “All this was a play and all the sentence and everything was decided before the trial and what happened in the court had no influence on the sentence or the case.”

In retrospect, it now appears that not just the trial of Dr. Orlov but the Helsinki agreements themselves were a kind of play in which the Soviet authorities pretended that an ideological system imposed through force could honour solemn human rights commitments without undermining its own existence, and the Western signatories pretended to believe them.

At least 18 people connected with Helsinki agreement monitoring groups have now either been arrested or sentenced in various parts of the Soviet Union. Although attention has focused on Dr. Orlov, Alexander Ginzburg, and Anatoly Shcharansky, who were the founders and key members of the Moscow group, four members of an affiliated group in the Ukraine, including the Ukrainian poet Mikola Rudenko, have already been convicted of anti-Soviet agitation and received maximum sentences.

Dr. Orlov was in many respects well qualified to organise a dissident committee which sought to exert pressure on the authorities to translate public Soviet international commitments into genuine rights for Soviet citizens. A member of the Communist Party until his expulsion in 1956 for going too far at a party meeting in criticising the practices of the Stalin era, he moved to Armenia where he was able to find work as a physicist and in time became a corresponding member of the Armenian Academy of Sciences.

A specialist in high energy particle accelerators, Dr. Orlov returned to Moscow in 1972 and began work at the Institute of Terrestrial Magnetism and Propagation of Radio Waves but was fired after sending a letter in 1973 to Mr. Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet President, in which he called for democratic reforms and connected the question with the campaign against Academician Andreo Sakharov.

Dr. Orlov became a member of the Soviet chapter of Amnesty International and in May 1976 founded the Helsinki monitoring group which for the first time drew together all the strands of Soviet dissent—the democratic movement, the Jewish emigration movement, and the religious rights movement—into a single organisation based on explicit Soviet acceptance of an international agreement.

In a country without a free Press, the Helsinki group quickly established itself as the best—and in many instances, the only—means of verifying whether Soviet pledges to honour freedom of religion and the right to emigrate, and to allow reunification of families, were being honoured in practice. The group demonstrated an ability to gather accurate, factual information on the Soviet human rights situation from sources all over the country.

Although Dr. Orlov’s trial was a trial of the Helsinki monitoring committee, the word “Helsinki” was never mentioned. The parade of prosecution witnesses—who apparently in the eyes of the authorities made defence witnesses unnecessary—demonstrated in their glowing encomia to Soviet power the kind of impartiality the West can expect if the Soviet Government is left to evaluate its Helsinki fulfilment record completely on its own.

The challenge to the Western signatories of the Helsinki agreement implicit in the trial of Dr. Orlov has been clearly laid down. The Soviet Union is not going to allow anyone to challenge the disparity between what it promises in international forums in order to appear respectable and what it will tolerate for fear of losing control. It is now up to the Western powers to decide how to react.

1 Dr. Orlov, the leader of the Helsinki monitoring group was on trial for “anti-soviet agitation.” He was arrested in February, 1977.

Financial Times, Thursday, July 27, 1978

Soviet dissent after the trials

Shaken, but Ready to Rise Again

With sentencing of Dr. Yuri Orlov, Alexander Ginzburg and Anatoly Shcharansky, an uneasy sense of ideological calm has settled over Moscow. The Soviet authorities’ bid to destroy the groups set up to monitor the 1975 Helsinki accords has shaken the dissident movement, which never, in any case, contained more than a few hundred activists, and it will need time to reorganise.

However, it is virtually certain that the authorities’ attempt to crush dissent through long prison and exile sentences, but without full recourse to Stalin’s bloody methods, will fail.

With each wave of arrests and trials since the trial of the writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel in 1966, the end of the dissidents has been predicted. On each occasion, they have resurfaced with renewed energy.

The resilience of Soviet dissent lies in the facts that it is both an inevitable response to the complete lack of individual political rights, and a specific subculture which, because its members have chosen to join it fully aware of the risks they run, is ineradicable under present circumstances.

The Soviet Union, although more tolerant than it was in Stalin’s time, employs intensive police surveillance, ubiquitous informers, eavesdropping and letter opening. The Soviet citizen has in practice no right to free speech or assembly, no ability to form independent organisations or to publish opposing opinions. As the trials of the dissidents demonstrated, there is no guarantee of due process of law.

The dissident movement has various elements—democratic dissidents, nationalists, the religious rights movement, Jews seeking to emigrate—but in general consists of people who have dedicated themselves to working for the creation of reliable political rights as the only means through which their other goals can be effectively realised.

The dissidents are self-selected. They know their activities will end their careers and could mean that they go to prison. The need to be prepared to accept the grim consequences is why the dissident movement is so small numerically, but also so wide in influence (almost everyone in the Soviet Union is aware of it) and so difficult to suppress. Any dissident gathering is peopled by those who have been to the labour camps or are soon to go, and they are hard to intimidate.

The present campaign against dissent, which is only the latest of a series dating from the late 1960s, began with the seizure of Alexander Ginzburg in February 1977 outside a pay telephone booth near his wife’s apartment. It grew out of a basic feature of Soviet life, the Soviet desire to make solemn international human rights commitments without loosening the State’s total control.

The Soviet authorities signed the Helsinki accords aware that they could not honour them. With their formation of the Helsinki agreement monitoring group in May 1976, the dissidents accepted the implicit challenge to hold the authorities to their word.

The arrest of more than 20 members of “Helsinki” groups in Moscow, the Ukraine, Lithuania, Georgia, and Armenia in the last year and a half and the sentencing of 16 of them has deprived the movement of its most effective leaders but has far from destroyed it.

On July 16, the day after Anatoly Shcharansky was sentenced, remaining Moscow dissidents crowded into the apartment of Dr. Andrei Sakharov, the Nobel Peace Prize winner, to reiterate their determination and announce the appointment of a new member of the Moscow-based Helsinki Group, Professor Sergei Polikanoff, a nuclear physicist and corresponding member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Professor Polikanoff said he was joining the group in light of recent “significant losses” and would contribute to its work in any way he could.

The disparity between the freedoms the Government professes to guarantee and those it actually grants is typical of the Soviet Union. The authorities make human rights commitments because they want to attribute the apparent unanimity of Soviet society to Marxist development rather than to the absence of freedom. Unanimity in the Soviet Union, exemplified perhaps in the Supreme Soviet, which may be the world’s only parliament never to have voted no, is always held to be voluntary.

Soviet authorities may thus ignore ostensible rights and freedoms but can never disavow them. When two dissidents went to the Moscow City Council last year to say that they planned to hold a demonstration in Pushkin Square to mark United Nations Human Rights Day, they were not told that such a demonstration would he illegal, but merely advised that if hooligans from nearby cafes decided to beat them up, it would be exclusively their fault.

The atmosphere of unreality which this situation creates is part of the life here and limits the extent to which the dissidents, who always attempt to take human rights commitments literally, can pressure the authorities to honour the rights the authorities have themselves promulgated.

When, however, the Soviet Union signed the Helsinki agreements in which it derived tangible benefits such as Western agreement to the European territorial status quo in exchange for specific Soviet undertaking on human rights, the situation changed. If the West was serious about compliance, the Western powers would need information about Soviet violations which only the dissidents could supply and, for the first time, the dissidents would have a directly concerned external ally.

The crackdown on dissent, which has been unprecedentedly thorough has often been depicted as a response to President Carter’s human rights campaign. In fact, the interrogations and searches which are normal preparations for arrest, began before President Carter assumed office and the authorities would have almost certainly acted to suppress the Helsinki group regardless of who had been in the White House.

The Soviet Union was born of a successful conspiracy and perhaps acting out of unconscious memory, the authorities immediately suppress any form of independent organisation. This is in no way surprising. The Communist Party’s dominance of all organisational life—political, religious or cultural—means there is a social vacuum in the Soviet Union which would immediately draw in a wide range of discontented elements were it allowed to be utilised.

The Helsinki group, in the eight months during which it operated freely, established a network of contacts all over the country, and began receiving an enormous volume of mail. If allowed to exist, it could have become an institutionalised internal opposition with wide sources of information and important foreign contacts.

President Carter’s human rights campaign far from inspiring the arrests, may actually have helped the dissidents in the long run, by emphasising to the Soviet leader the continuing outside interest in the dissidents’ fate.

The international reaction to persecution of dissidents for attempting to exercise rights officially endorsed by the Soviet Government and generally acknowledged to be basic to human dignity, sets limits on Soviet behaviour the system would never generate itself. There will be no protest demonstrations in Red Square if Dr. Sakharov is arrested but the Soviet authorities must consider what would happen outside the country and to the Soviet Union’s prestige.

Part of the reason the Soviet Union signs international human rights agreements in the first place is because it wants international respectability. The Soviets will probably continue to sign such documents if, for no other reason, out of a reluctance to disqualify themselves as suitable signatories.

What the Soviet authorities may not fully realise is that the rest of the world, which does not accept the Soviet definition of the individual as without political rights before the State, will probably continue to react. The continuance of mendacious political trials backed by the full authority of the Soviet State is likely, therefore, to be a source of tension between Russia and the West for years to come.

It may be hoped, however, that, the dissidents’ selfless activities—so apparently fruitless—may over time and with the help of this Western reaction be a source of pressure on the Soviet Union to become less closed and rigid.

International Conference Trento, Friday/Saturday, December 6–7, 2002

Soviet Dissent and the Cold War

During the Cold War, the secret that the Soviet Union sought to hide from the West was its fundamentally ideological character. Although the Soviet system was animated by the drive to change human nature and remake reality, the Soviet Union depicted itself as a democracy that differed from Western democracies only in the population’s extraordinary degree of unanimity.

The Soviet Union boasted an array of supposedly democratic institutions—trade unions, courts, a parliament and a press. Faced with this democratic façade, it was often easiest for Western representatives to treat the Soviet Union, if not as a democracy, then at least as a country whose motives were those of any great power. The ideological underpinning of the Soviet state was frequently ignored.