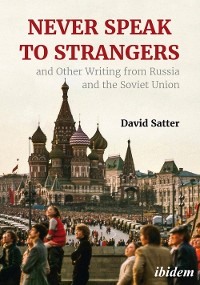

Never Speak to Strangers and Other Writing from Russia and the Soviet Union

In this context, the Soviet dissidents were important because they spoiled the mirage of voluntary unanimity that the Soviet regime took pains to construct. Because of their dedication and bravery (and the repression that their courage inspired), the democratic façade of the Soviet Union was discredited and the ideological nature of the East-West confrontation because impossible to conceal.

The Soviet dissident movement during the Cold War had an important effect on both the Soviet Union and the West.

In the case of the West, the dissident movement acted to push Western societies toward attention to first principles, even unwillingly.

The first effect of the dissident movement was its impact on Western public opinion. The emergence of protest within the Soviet Union demonstrated to many in the West that the surface calm of Soviet society was misleading. Soviet leaders continued to speak about the "total political and ideological unity of the Soviet people" but due to the activities of the dissidents, this claim became increasingly hollow.

First, the dissidents revealed the mechanism of political repression in the Soviet Union. They did this by speaking openly, in that way, refusing to play the roles assigned to them as Soviet citizens in the nationwide political play. This defiance led to arrests that were publicized by other dissidents who were arrested in turn. As the number of arrests grew, more information became available and other dissidents compiled and made public accounts of the system of labour camps and psychiatric hospitals that was used to enforce political conformity. It became undeniable that element holding the system together was fear.

At the same time, the dissidents, by gathering and circulating information, identified the hidden fault lines in Soviet society, calling attention to the plight of persecuted groups—Uniates, Pentecostalists, Jews and Germans seeking to emigrate, nationalists, worker-activists and others—whose situation had been little noticed or poorly understood.

The dissidents also wrote and helped to produce and circulate works of analysis and literature that constituted a free culture. These works, when they became available in the West, discredited the Soviet "experiment" in ways that works written by those outside the society rarely could.

The effect of the dissidents’ activities was to establish a source of truthful information independent and, in some cases, competing for attention in the West with the disinformation apparatus of the Soviet state. This proved highly important. The dissidents were not able to give the West a complete understanding of the character of the Soviet system but they provided enough information to raise doubts about the Soviet Union’s intentions.

By affecting Western public opinion, the Soviet dissident movement, in turn, had an impact on the policies of Western governments. There were those in Western governments who would have preferred to deal with the Soviet Union “pragmatically,” concentrating on what they imagined to be “mutual interests.” But, in many Western countries, the repression of the dissidents had aroused public opinion and made such policies politically impossible. With the expansion of detente era measures advantageous to the Soviet Union, e.g. trade, scientific exchanges and arms control treaties, all of which presumed a degree of trust, there began to be calls in the West for accompanying steps to make the Soviet Union more open and to protect human rights. This led to such measures as the Jackson-Vanik amendment to the U.S. Trade Act and the 1975 Helsinki Agreements which, in exchange for Western acquiescence in the European territorial status quo, committed the Soviet Union to respect human rights and facilitate the free exchange of information. The emotions inspired by the struggle of the Soviet dissidents also helped to motivate the human rights campaign that was initiated under President Carter and represented the first attempt at an ideological counter offensive directed against the moral vulnerability of the Soviet Union.

Because the dissidents had an effect on Western public opinion and the policies of Western governments, they also influenced the policies of the Soviet government. The Soviet authorities could have crushed the dissident movement overnight but behind the dissidents stood the West and it was this that gave the Soviet dissidents their strength.

The first way in which the dissidents influenced the Soviet government was by forcing it to grant limited freedom of written expression. In 1965, Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel were sentenced to long labour camp sentences for publishing their works abroad. The international reaction to the case, however, did serious damage to the image of the Soviet Union. Sinyavsky and Daniel served out their labour camp terms but the Soviet Union never again imprisoned a writer for his writing. Alexander Solzhenitsyn was forcibly exiled and Vladimir Voinovich, Vasily Aksyonov, and Georgy Vladimov emigrated under pressure. But in the meantime they and other writers were able to create the non-communist Russian literature that helped to sustain the cultural and moral values of more than one generation of Soviet citizens.

The activities of dissidents also compelled the Soviet authorities, for the first time, to allow mass emigration from the Soviet Union. Before the 1970s, it was virtually impossible to leave the Soviet Union legally. With the birth of the Jewish emigration movement, however, the Soviet authorities faced a choice between allowing Jews to emigrate or accepting the political cost of repression. The decision was made to allow Jews to emigrate under a formula—that they were returning to their “historic homeland”—that opened emigration for Soviet Germans as well.

Finally, the dissidents influenced the government’s policies in the treatment of dissenters themselves. Yuri Galanskov, one of the earliest dissidents, died in a Soviet labour camp but for many years afterward, despite extremely harsh treatment, the Soviet authorities tried to keep well known dissidents alive. They also spaced out the arrests of prominent dissidents, allowing many of them to continue their activities, declined to arrest Sakharov (although he was exiled) and allowed some dissidents to emigrate. As a result, dissent became a somewhat more viable option for Soviet citizens.

The concessions that the Soviet dissidents were able to force from the authorities wrought important changes in Soviet society.

In the first place, Moscow, and, to a degree, Leningrad became centers of serious political discussion. The authorities did not want mass arrests in the capital that would, on the one hand, embarrass them internationally, and, on the other, create new dissidents so they behaved with tolerance toward expressions of opinion as long as they did not take public form. The result of these tolerated conversations was that, when perestroika began, alternatives to the communist system had already been considered.

At the same time, the stream of free information that the dissidents provided (much of it broadcast back to the Soviet Union by the Western radio stations) helped to give moral orientation to a large part of the Soviet intelligentsia. By their example, the dissidents also demonstrated that resistance was possible. As a result, when the controls were drastically loosened in the Soviet Union under Gorbachev, there were millions of people who were immediately ready to assume an active political role.

The story of the Soviet dissidents during the Cold War is the story of people whose power derived solely from the power of an idea. By refusing to participate in the obligatory ideological play in the Soviet Union, they became de facto the defenders of the values of civilization that the Soviet system had been organized to destroy.

It was sometimes argued in the West that the dissidents did not deserve the attention that they received in the Western media, that they were few in number and that they represented no one but themselves. This logic, which would have made sense in a democracy, was completely fallacious when applied to the Soviet Union where political strength derived from ideological subservience and opposition was inevitably, the opposition of an idea. The dissidents were powerful because the idea was powerful and, under totalitarian conditions, they found the strength to represent that idea.

Financial Times, Monday, September 11, 1978

Why Moscow Has Georgia on Its Mind

Whatever others may think of him, Stalin is far from discredited in his native Georgia. His portrait, carried—by street vendors, seen in shoe shine kiosks or glimpsed through labyrinthine courtyards on the walls of workers’ flats, lends a macabre touch to the life of this otherwise lush and sunny republic.

“Everyone makes mistakes,” as one Georgian woman put it.

There is a Stalin museum in Stalin’s birthplace, Gori, a modern town of 50,000 inhabitants set in a valley between green hills, as well as a statue of Stalin flanked by silver pine trees in front of the city hall.

In the centre of Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, streams of traffic use the Stalin embankment and on a mountain 2,000 feet above the city, children enjoy rides at the Stalin amusement park.

All this, however, probably says more about the Soviet attitude towards Georgia than about any nostalgia for Stalin.

Georgia differs from Russia historically, temperamentally and culturally, and since Stalin has been regarded as a national hero by those poorer workers who were least affected by his purges, it is apparently deemed prudent to encourage a reverential attitude to him in an attempt to tie Georgian loyalties more firmly to the Soviet state.

Just how different Georgia is from the rest of the Soviet Union becomes clear walking down Rustavelli Street, Tbilisi’s main avenue. It is lined with French baroque style buildings and spreading trees, and feels more Latin than Russian.

Beyond Rustavelli Street, Tbilisi is a city of crumbling stone buildings with iron latticework balconies and terraced Caucasian one-storey cottages on the sides of hills. The mountains which characterise the republic are visible in the distance. Much of the old city centre is preserved and Tbilisi, unlike other Soviet cities, has distinct neighbourhoods.

The atmosphere on Rustavelli Street on a typical summer night is friendly and relaxed. But the street has also witnessed striking manifestations of Georgian nationalism, as on April 14, when the largest mass demonstration in more than 20 years took place to protest against an attempt to abolish Georgian as the republic’s official language. The demonstration showed that Georgia’s accommodation to the Soviet state is potentially uneasy and requires concessions to national feelings.

The draft text of the new Georgian constitution had been published and, unlike the constitution of 1937, it contained no reference to Georgian as the official language of the republic but only granted the right to use the native language or other languages of the USSR during the “discussion” period in factories and offices prior to the formal adoption of the document. But the usual unanimous approval was not forthcoming. Heated arguments broke out, especially in academic and scientific establishments. Petitions began to circulate.

As April 14, the day when the constitution was supposed to be adopted, approached, it became obvious that thousands of people were going to gather outside the Supreme Soviet building to demand the retention of Georgian as the official language and the authorities, perhaps sensing the costs of suppressing the demonstration, acted instead to infiltrate the demonstration and direct it away from anything overtly anti-Soviet toward the one goal of reinstating the Georgian language.

There were at least 5,000, and perhaps 10,000, persons on the street on that day, halting all traffic. The situation, however, remained under control. The only placards contained quotes from Georgian classics and lines from a Georgian children’s reader. The opening of the Supreme Soviet session was delayed and the demonstration ended when Eduard Shevarnadze, the Georgian communist leader, appeared before the demonstrators and told them Georgian would be retained as the official language.

Almost all communication in Georgia is in Georgian, so the proposed constitutional change would not have, had great practical effect. The local news programme is broadcast in Georgian seven times a week, in Russian only once. The Georgian language newspaper, Kommisti, has five times the circulation of Zarya Vostoka, its Russian counterpart. There are Georgian plays, books and an active film industry.

But the retention of Georgian as the Republic’s official language is of as much symbolic significance in 1978 as 56 years earlier, in 1922, when Lenin accepted it in a “historic compromise” as part of an effort to refute claims that the Bolsheviks would eradicate Georgian culture.

The crowded, winding streets, the markets piled high with fruits, vegetables and flowers and the modish dress of Georgian young people all provide reminders that Georgia has its own distinctive character and a history far pre-dating that of Russia.

This sense of history and an awareness of its ironies may contribute to the fact that normally there is an atmosphere of easy tolerance within Georgia. There are Jewish, Armenian and Azerbaijani residential sections near the old synagogue. The Armenians sometimes irritate their neighbours by packing the Tbilisi versus Yerevan soccer games and cheering for Yerevan. But there is little real hostility among its peoples.

The fact remains, however, that Georgia, with its flourishing agriculture, its history, language and culture, has all the attributes of an independent nation but exists only as a compartment of the Russian-dominated Soviet state.

The Soviet system offers a Marxist-Leninist substitute for most of the components of any traditional culture. Atheism is a substitute for traditional religion, dialectical materialism replaces national history and socialist ideology sets limits on cultural expression. That leaves language as the pre-eminent symbol of national identity.

The impossibility of changing the situation, and the Soviet skill in placating the Georgians with national symbols and timely concessions seem to have created a mood of resigned cynicism. The Georgians, who make up 70 per cent of the republic’s population, make the best of the situation: “There are few active dissidents but everyone ‘thinks differently.’ No one believes what he reads in the newspaper,” as one Georgian intellectual put it.

Georgian culture is not free to establish its own character any more than is the national culture in the other non-Russian republics. The language issue which provoked the Tbilisi demonstration on April 14 has great symbolic importance elsewhere. But in each republic there are different points of conflict between socialist ideology and native traditions. In Lithuania, for example, the intensity of national feeling stems in part from the Soviet suppression of the Catholic religion. In Georgia there is, in addition to general cultural resentment, a specific resistance to the rigidities of the planned economy.

Soviet citizens elsewhere uncharitably attribute a penchant for corruption to the Georgians. In some cases, it could just as easily be described as impatience with centralisation and a persecuted talent for private enterprise.

In the live and let live atmosphere which prevailed before the accession of Mr. Shevarnadze in 1972, the living standard in Georgia was reputedly the highest in the Soviet Union. It may still be. A not inconsiderable portion of the wealth is derived from the unofficial but highly organised purchase of fruits, flowers and vegetables and their resale in northern cities.

The practice has been mostly brought under control, partially because of the Government’s decision to pay higher prices to farmers for their produce. But it has not been eliminated.

The Press is full of stories about speculators being caught trying to smuggle fruit out of Georgia or manufacturing bootleg liquor in their bathtubs. Recently, three lorries full of fruits and vegetables and protected by armed guards were stopped at the border between Georgia and the Russian republic by a night patrol.

The crackdown on corruption in Georgia was initiated by Mr. Shevarnadze after he replaced the former Georgian communist leader, Mr. Vasily Mzhavandze. Thousands of Georgian officials were fired or deprived of their influence and tough penalties began to be meted out to bribe takers and black market operators. One response was a series of fires and bombings, beginning with the torching of the Tbilisi opera house in 1974 and culminating in the bombing of the Council of Ministers’ building in 1976 for which a man was reportedly shot.

Mr. Shevarnadze’s activities after taking office had the potential to evoke considerable resentment on the part of ordinary Georgians tempted to view him as Moscow’s agent assigned to bring the republic in line, Mr. Shevarnadze’s personal qualities, however, unusually in the case of a Soviet leader, have won him widespread respect.

Mr. Shevarnadze has established a reputation of integrity and unlike the secretive Communist Party leaders in Moscow, is willing to appear at the centre of events. Last year he single-handedly quelled a soccer disturbance during a game between Tbilisi and Voroshilovgrad by appearing alone before the crowd and promising to review the film of a disputed play.

Even Mr. Shevarnadze, however, has not been able to extinguish the Georgians’ enterprising spirit, or the resentment against Soviet control. Jobs as taxi drivers and store managers, and places at university, are no longer for sale, but a visitor cannot fail to notice that blue jeans—Soviet black market item number one—are more common in Tbilisi than elsewhere in the Soviet Union. In the central market, amid the piles of grapes, peaches, melons and pears, caviar is said to be still available for 100 roubles a kilo to those who know whom to ask and how.

Financial Times, Thursday, October 5, 1978

Armenia

Angry Nationalist Struggle

Against Soviet Power

On Saturday afternoon, January 8, 1977, a sudden explosion ripped through a carriage of the Moscow metro as it approached the Pervomaiskaya station. The carriage, filled with passengers including many children, was destroyed.

Official reports minimised the casualties, but a man who took part in the rescue work said that he saw at least 30 dead on the station platform. Scores more people were terribly injured and many died later in hospital. It was the worst act of terrorism in modern Soviet history.

In the months after the explosion, the KGB interrogated dissidents, and rumours swept Moscow that the blast was the work of Zionists. There were many, however, who believed that the trail might ultimately lead not to traditional dissenters but to hot, dusty Yerevan where the historically ill-fated Armenians have shown signs of restiveness under Soviet rule.

Yerevan is a city of lush parks, stolid, rose-coloured apartment blocks built of volcanic rock and columned Government buildings on broad squares. The whites and greys of one-storey houses line the sides of arid hills where vines coil around iron frames on the pavement, creating canopies.

In March this year, two Armenians, Mesrup Saratikyan, and his brother were seized in Yerevan and taken to Moscow, bringing to five the number of Armenians from Yerevan arrested in connection with the metro explosion.

The other three suspects were detained in Moscow and Yerevan in November, 1977. They included Yakov Stepanian, a former political prisoner, and a second unidentified man. They were reportedly arrested after planting a bomb at the busy Kursk station in Moscow which serves trains to the Caucasus. The third man was Stepan Zatikian, who once served a labour camp sentence for anti-Soviet agitation.

On June 7 this year, the Soviet news agency Tass said in a terse dispatch about the metro explosion, that “the criminals have been found by the state security committee organs” and that the men had “admitted their involvement.”

In Yerevan, the news of the arrests had leaked out much earlier through relatives of the accused and dissidents who had been questioned about them. The fact that anti-regime Armenians were apparently involved in the metro bombing had a chilling effect on organised Armenian dissent, which has been supressed in repeated waves of arrests since the early 1960s.

The atmosphere in Armenia is more relaxed than in Moscow. There are attractive cafes and the Soviet Union’s only gallery of modern art. Old men play chess in the park and young people gather on summer nights around the fountain in Lenin Square, where Western rock music is broadcast over a loudspeaker.

Despite this, there has been an active dissident movement in the area since at least 1963 and many more people have apparently been arrested in Armenia than in neighbouring Georgia, where nationalism is also a basic issue. Armenian nationalism has a more emotional edge because of the memory of the 1915–18 massacres at the hands of the Turks.

Many Armenians, particularly members of the older generation, give the Russians credit for saving the Armenians from annihilation. “If it hadn’t been for the Russians,” one taxi driver told me, “The Turks would have murdered every one of us.” Others, however, express regret that the Armenians survived the Turkish massacres only to be delivered into the hands of the Stalinists. “The nationalists feel that Soviet power interferes with the ability of Armenians to act for themselves,” one woman said.

The monument to the 1.5m victims of the 1915–18 massacres in Yerevan is a tall obelisk rising starkly to a needle point and, nearby there is a circular mausoleum of 12 inclining pillars around an eternal flame. Oddly, the monument was not built until 1965, after decades when no memorial was allowed. Even today, there is little mention of the Turkish massacres in Armenian schools or in the Press.

Armenian nationalism, which draws some of its force from a sense of historical victimisation, first surfaced in 1963 when more than 200 people demonstrated peacefully outside Communist Party headquarters. They were asking for increased protection for the Armenian language. Then in 1965 a group called “free Armenia” tried to set up a newspaper but those involved were arrested and their press destroyed.

By 1968, a number of nationalist groups had formed, the most important of which was the National Unification Party I (NOP), which succeeded in publishing Armenia’s first genuine underground newspaper, “Paros,” which is Armenian for “beacon.”

NOP’s goal was independence and the unification of the Armenian lands, including Turkish Armenia and Karabach Nakhichevan, a part of Soviet Azerbaijan. Two issues of “Paros” appeared with a circulation of 3,000 each before NOP was suppressed and its press destroyed.

Among the first NOP members to be arrested and subsequently convicted of anti-Soviet agitation were Shagin Arutunyan, later to become a founding member of the Armenian Helsinki Agreement monitoring group, Heikaz Khachatarian, an Armenian artist, and Stepan Zatikian, arrested in Yerevan in November 1977 in connection with the Moscow metro explosion.

In 1976, Mr. Arutunyan helped found the Armenian Helsinki group, which hoped to operate openly. The group collected information about deaths in prisons, interference with contacts with Armenians abroad and persons denied permission to emigrate.

Virtually none of this information sent to Moscow ever reached its destination.

Mr. Arutunyan was beaten by KGB and militia men on the morning of December 22, 1977, and then charged with hooliganism and sentenced to three years in a labour camp at a trial from which his wife was barred. Eduard Artunyan, another Helsinki member and a scientist, was put in a mental hospital and Robert Nazarian, a third Helsinki group member, was also arrested on December 22 and is awaiting trial on charges of anti-Soviet agitation. The charge, carries a maximum penalty of seven years imprisonment and five years exile.