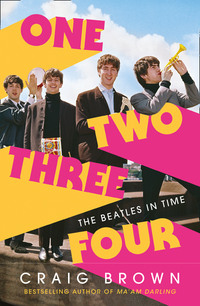

One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time

As the minibus left Speke Hall, Joe pressed a button and ‘Love Me Do’ came bursting from the speakers. ‘Whassis rubbish then?’ shouted an Australian at the back.

‘I can see who’ll be walkin’ back!’ said Joe. ‘When he gets off the bus, let’s jump ’im!’ It was all very merry.

Soon we were in Forthlin Road, the kind of unassuming row of nondescript houses most National Trust members would normally drive through, rather than to.

The National Trust bought 20 Forthlin Road in 1995, on the suggestion of the then director-general of the BBC, a Liverpudlian called John Birt,1 who had noticed it was up for sale. Seven years later the Trust also acquired John Lennon’s childhood home, ‘Mendips’, in Menlove Avenue, after it had been bought by Yoko Ono. In a statement around that time, she said: ‘When I heard that Mendips was up for sale, I was worried that it might fall into the wrong hands and be commercially exploited. That’s why I decided to buy the house, and donate it to the National Trust so it would be well looked after as a place for people to visit and see. I am thrilled that the National Trust has agreed to take it on.’

But it was a decision not welcomed by one and all. Tim Knox, at that time the National Trust’s head curator,2 declared himself ‘furious’. The Trust’s usual criterion for taking on a property – that the building should have intrinsic artistic merit – had, he felt, been abandoned in pursuit of shabby populism. ‘They’re publicity coups – not serious acquisitions,’ he said, adding, only half-jokingly, ‘Now we’re going to take four properties on so Ringo doesn’t feel left out.’

Others agreed. ‘Architecturally, the house is no more or less interesting than any other arterial, pebble-dashed semi in any other middle-class suburb,’ observed the design critic Stephen Bayley.3 ‘Its special value comes from the vicarious, mystical contact with genius. The problem for the Trust’s architectural historians is that, since the house was pretty much denuded of its contents, there is no possibility of vicarious, mystical contact with the genius’s telly set, kitchen unit or any other artefact that might afford an insight into the inspiration that gave us such a torrent of brilliant words and music. So, they set about faking it.

‘The National Trust … prides itself on its access to expertise. It has some of the world’s leading architectural historians on its staff and they went out to buy the stuff to recreate Lennon’s home. But when scholarly expertise is focused on junk, in a magical mystery tour of some dingy Liverpudlian dealers, scholarly expertise looks silly. A crap medicine cabinet is admired for its authenticity. The lino is subject to scrutiny worthy of a Donatello relief sculpture. They can find the conical legs of the television set, but not the set itself … If you are doing the long and winding road of fakery, where do you stop? In the dreamworld of folk memory and fantasy, is the answer.’

The National Trust remains undaunted. ‘Imagine walking through the back door into the kitchen where John Lennon’s Aunt Mimi would have cooked him his tea,’ reads its awestruck introduction to Mendips. It treats the house as a religious shrine, a place of pilgrimage. ‘Join our fascinating Custodian on a trip down memory lane … John’s bedroom is a very atmospheric place in which to take a moment with your own thoughts about this incredible individual …’

Pilgrims to Mendips face rules and regulations stricter than those for the Sistine Chapel. ‘Any photography inside Mendips or duplication of audio tour material is strictly prohibited. You will be asked to deposit all handbags, cameras and recording equipment at the entrance to the house.’

It can’t be long, surely, before one of the faithful witnesses some sort of miracle at Mendips – a blind man sees, a crippled man rises up and walks, a little girl sees John’s mother Julia in a vision – leading yet more pilgrims to flock to Menlove Avenue, forming orderly queues for the chance to see the exact spot where Julia met her end.

While our minibus was decanting its passengers, many more were pouring out of a ‘Magical Mystery Tour’ coach, and behind them, four Germans were stepping out of a black cab. The gateway to 20 Forthlin Road was pullulating with visitors from all over the world, wearing Beatles T-shirts and posing for selfies. The metal sign outside announces ‘The proud family home of the McCartney family, Jim, Mary, Paul and Mike. Accessible via the National Trust.’

I started edging towards the front of the queue. I had booked way in advance and paid £31 (including guidebooks) for an official tour of both Beatles houses, and I was worried that people on unofficial tours would creep their way past the guide and elbow their way into Paul’s house in my place. Luckily, Joe the driver was standing by, monitoring the chosen few. Our little group marched self-importantly into the front garden of 20 Forthlin Road, and the gates were then satisfyingly closed on everybody else.

Our National Trust guide introduced herself as Sylvia. She conducts 12,000 people a year around Paul’s childhood home, twenty at a go, four times a day. Her voice has a hint of Hyacinth Bucket. Standing in the garden, she welcomed us to 20 Forthlin Road. This, she said, was where Paul lived for eight years: ‘very important years musically. George Harrison was an early visitor. George would bring his guitar.’

A buzz went around. Stephen Bayley’s promise of mystical contact seemed to be taking shape. ‘And then when John Lennon started to come down to the house, John would take a short cut through the golf course to get here on his bicycle, taking less than ten minutes through the golf course. And in the room behind you there –’ she gestured ‘– that’s where John and Paul sat down and began writing songs together. By the time Paul left here, it was right at the end of 1963, so the Beatles had already got hits in the charts, they were appearing on television. Paul was still coming back though, that was still his bedroom up there, right until the end of 1963. He was the last Beatle to move to London. So when the McCartneys came – sorry, are you recording?’

I froze. I had been covertly recording Sylvia on a mobile phone, but it turned out that she was talking to one of the Australians, standing closer to her. He assured her that, no, he wasn’t recording. ‘No?’ she replied, suspiciously. ‘I’m sorry, I just don’t like it,’ she muttered, before struggling to regain her thread. ‘Erm. When. Erm. The McCartneys. So. Erm. When the McCartneys came to live here, erm, these were all council houses, so that means the McCartneys didn’t own this house, it was social housing, everybody paid rent.’

Unbeknownst to Sylvia, I carried on recording, slyly holding my phone at a casual angle so as not to excite her attention. It made me feel on edge, as though I were pocketing household products within spitting distance of a store detective.

‘Over the years, you can see what’s happened. People have bought the houses, and they’ve changed the doors and windows. When the National Trust got this house, twenty-two years ago now, there were new windows at the front, but the Trust saw that a house across the street still had these original windows, so they did a deal, they got the new ones and we got the old ones back again. So now it looks exactly as it did when Paul and his family lived here.’

We all gazed dutifully at these front windows, marvelling that they now looked just like they would have looked before they looked different. Meanwhile, my phone was recording, and I was growing increasingly worried that Sylvia would notice, and denounce me.

‘OK, so if anyone wants a photograph at the front of the house, just give me your phone or your camera. Move to the end of the window so I can fit you in, bunch up a bit for me.’ Groups of visitors stood beaming in front of Paul’s old front door, or what would have been Paul’s old front door if it had been Paul’s old front door, which it wasn’t. ‘Is that everyone? Is that it?’

Sylvia warned us that we were not allowed to take photographs in the house or the back garden. ‘There’s a special reason here. You’ll see inside we’ve got Mike McCartney, Paul’s younger brother’s, copyright photographs all around the house. It’s lovely to have them. And you’ll enjoy them. But he’d take them away if people had photographs of them.’

We moved into the back garden. The National Trust blurb suggests ‘5 things to look out for at 20 Forthlin Road’. One is described as ‘The Back Drainpipe: After Paul’s mum died, his father would insist that the two boys were home in time for dinner, if not they were locked out. When this inevitably happened, Paul and Mike would run round the back of the house, climb up the drainpipe, and through the bathroom window, which they always left on the latch for such an eventuality.’ Sylvia repeated this anecdote, almost word for word, as we all stared at the drainpipe – or, to be accurate, the replica drainpipe.

‘So if when you come in you could hand me your bags and cameras, and if you’ve got a mobile phone can you switch if off and hand it in, so we don’t want to see mobile phones in your pockets.’

With that, Sylvia ushered us inside. Everyone lined up to give her their phones and cameras, as though crossing the border of a particularly nervy country. She then locked them all in a cupboard under the stairs. Disobediently, I kept my mobile phone in my pocket, and immediately regretted it. Throughout the rest of my visit I was terrified that someone would phone me, and the ringing would act as an alarm bell and I would be unmasked and shamed.

We all squeezed into the sitting room, decorated with three different types of wallpaper – ‘the McCartney family bought end-of rolls’ – none of them original. The brown armchair, chunky 1950s television and corner table were not original either, and nor were the rugs. ‘This is the room the McCartneys called the front parlour. The National Trust has recreated it with the aid of photos and family memories,’ said Sylvia. In response to a query she said that no, the piano was not original. ‘Paul still owns his father’s house, and he stays in it when he comes to Liverpool. And that’s where the original McCartney piano is. Jim used to play “The Entertainer”. Do you know that song – by Scott Joplin? If you think of Scott Joplin and “When I’m 64”, you can really tell the influence … Father Jim was a good self-taught musician. Paul followed in his father’s footsteps. After a few lessons, he said, “I’ll be just like my Dad. I’ll teach myself.” … He composed “World Without Love” here, and the very beginnings of “Michelle” were written here. And “Love Me Do” – they were sitting here when they wrote it … Paul sat here and wrote “I’ll Follow the Sun”.’ She pointed to a photo of John and Paul on the wall. ‘The song they’re finishing in this picture is “I Saw Her Standing There” … Another song they finished off was “Please Please Me”.’

Every now and then, Sylvia tried to make things personal, beginning her sentences ‘Paul told me’ – as in, ‘Paul told me, “We had some sad years but most of the time we were really happy.” Or, ‘This was their dining room. Paul told me, “We never ate in here after Mum died.”’ She added, ‘Paul told me, “A lot of people think ‘Let it Be’ is about the Virgin Mary, but it was about my mother, who would always say “Let it be.”’ I had read these stories countless times over the years,4 but it obviously afforded Sylvia satisfaction to say that she had heard them direct from Paul; and perhaps in the coming years it would satisfy us, too, to say that we had heard them from someone who had heard them from Paul.

We shuffled into the kitchen. ‘The quarry tiles have not been changed. All the Beatles have stood on those quarry tiles – though Ringo only twice, as he came late.’ We peered down at the sacred tiles beneath our feet. ‘The Trust found the original white sink in the garden with plants in it and returned it to its rightful position.’ We gazed awestruck at the kitchen sink, imagining young Paul hard at work on the dishes.

Only the tiles and the sink are original to the kitchen, but the experts from the National Trust found feasible lookalikes for the rest: the packet of Lux soap flakes, the Stork margarine, the tea can, the biscuit tin, the wireless, the clothes horse. Photographs of all these items – the domestic equivalents of tribute bands – may be purchased on the National Trust website: photos of a 1950s record player, vacuum cleaner, bread bin, washing tongs, frying pan, kettle, clothes pegs, rolling pin. And everything has been diligently catalogued, like items from the Tower of London. A photograph of a wooden spoon (Date 1960–1962, 260mm; Materials: Wood) is described as ‘Historic Services,/Food & drink preparation, Summary: Wooden spoon, kept in mixing bowl on dresser’.

Alternatively, you can buy a photo of a tea strainer or a doormat or a frying pan or a coat rack or ‘Enamel bucket with black rim and handle with wooden grip, date unknown’.

The pride of the collection is surely ‘Dustbin: Metalwork, Date 1940–1960, Summary: Metal dustbin with separate lid (plus spare lid in Coal Shed)’. If you were a battered old dustbin, circa 1940–1960, just imagine how proud you would be to end up as a key exhibit in a National Trust property, with 12,000 visitors a year admiring you for looking just like the dustbin into which the McCartney family used to throw its rubbish!

While we were still squeezed downstairs, I became so scared that my phone would ring that I surreptitiously switched it off, and began taking notes instead. ‘The lino on the floors is just right,’ Sylvia was saying, ‘so we managed to track it down, and the cupboard where I put the bags, well, that was where Paul would hang up his jacket and sometimes his leather trousers. Excuse me, you’re taking notes. Why are you taking notes?’ With a start, I realised that Sylvia was talking to me. ‘Who’s it for?’

‘Me,’ I said.

‘I’m just checking you’re not a journalist.’

‘I am. I’m writing a book.’

‘Well, I don’t like you taking notes.’

‘Why not?’

‘Well, it’s just that a lot of what I say has been told to me by Mike, and it’s private information.’

‘But you’ve said you tell it to 12,000 people a year. It can’t be all that private.’

‘I’m sorry, it’s making me uncomfortable. What did you say your name was?’

And so there we were, arguing away in the McCartney front parlour on a very hot day in August. We finally came to some sort of deal that I wouldn’t write anything that Sylvia regarded as strictly private, but she kept throwing suspicious glances in my direction. I sensed my fellow visitors edging away from me, as though I had just broken wind.

Eventually we were permitted upstairs. Sylvia led us into Paul’s bedroom. On his bed sat an acoustic guitar, strung for a left-hander. Inevitably, this was not the actual guitar. A few records were also on the bed, along with a sketch pad and a copy of the New Musical Express. ‘We’ve collected all sorts of things he had in this room. For instance, the bird books – Paul was always a keen birdwatcher.’

‘This is strictly private,’ she added, looking daggers at me, ‘but Paul told me he always liked looking out over these fields, which belonged to the police training college. He liked watching the police horses in the back field.’

It was only later, browsing through the National Trust’s colour guide to 20 Forthlin Road, that I chanced upon this passage in Paul’s introduction: ‘The house looks onto a police training college, and we could sit on the roof of our shed and watch the annual police show without having to pay.’

1 John Birt, director-general of the BBC 1992–2000. In the summer of 1962 the seventeen-year-old Birt had a holiday job as a bouncer at Southport’s Cambridge Hall, where the Beatles were playing two consecutive evenings with Joe Brown and the Bruvvers headlining. After the first concert he and a friend were told to guard the door of the Beatles’ Green Room to keep out, in his words, ‘a score of emotional and tearful girls of my own age’. One of these girls turned out to be ‘the most beautiful girl in Formby. We saw her on the train to school each day. She was in a league of beauty of her own and paid no attention to any of us. No one in my circle had ever spoken to her.’ She pleaded with Birt and his friend to let her in to see Paul McCartney. ‘My friend said: “We’ll let you in to see Paul if you let us have a snog and a feel.” She immediately agreed and led us off to some backstairs [sic]. To my shame even at the time, I participated in the encounter despite her inert response. This unedifying experience was soon cut short and we led her back to the Green Room to find that the Beatles had gone. I rushed around in a guilty panic trying to locate Paul and, to my relief, found him at the bar. I retrieved the girl, and took her to Paul, who was with a crowd of admirers. He turned round, recognised me as the bouncer, realised I was there with a purpose and raised his eyebrows questioningly. I explained that I was with someone very keen to meet him and introduced Paul to the apparition at my side. He bowed graciously, and as I departed in embarrassment they were chatting politely to one another.’

2 Now the director of the Royal Collection.

3 Coincidentally, the very same Stephen Bayley who at the age of fifteen wrote the letter to John that spurred him to write ‘I am the Walrus’ (see here).

4 Most recently in the 2018 Paul McCartney Carpool Karaoke (50,000,000 views, 70,000 comments), in which Paul says, ‘I had a dream in the sixties, where my mum, who’d died, came to me in the dream and was reassuring me, saying, “It’s going to be okay, just let it be.” And I felt so great, like, it’s going to be great … So I wrote the song. But it was her positivity.’

In the New Yorker in February 2020, James Corden, who chaperoned Paul around Liverpool for his Carpool Karaoke, revealed that Paul had initially been reluctant to return to his family home.‘He said, “I haven’t been there since I left, when I was twenty. I just feel weird about it.”’

5

On 6 July 1957, Paul’s school friend Ivan Vaughan suggested they go to the church fête at Woolton, where two of his mates would be playing in a skiffle group.

Paul and Ivan looked on as a carnival procession left the church – a brass band, followed by Girl Guides and Boy Scouts and a succession of decorated floats, all led by the Rose Queen and her attendants. At the tail end came the organisers’ sole concession to modernity – a teenage skiffle group called the Quarrymen, playing on the back of an open lorry.

Once they had completed a circuit, the Quarrymen jumped off their lorry and set themselves up in a field just beyond the cemetery. Ivan and Paul paid threepence to see them. The first song they heard John sing was ‘Come Go With Me’ by the Del-Vikings. Paul looked on fascinated, not only by the chords John was playing, but by his ability to make things up as he went along: even then, he couldn’t be bothered to learn the words. Using this improvisatory method, John sang his way through ‘Maggie May’, ‘Putting on the Style’ and ‘Be-Bop-a-Lula’.

Between sets John wandered over to the Scout hut, where he knew his guitar would be safe. Elsewhere, crowds were enjoying a routine by the Liverpool City Police Dogs, while youngsters queued for balloons.

Paul wandered over to the hut with Ivan. He recognised John from the bus, but had never spoken to him: Paul had just turned fifteen, while John was nearly seventeen. Even at that age, John had an intimidating air about him: ‘I wouldn’t look at him too hard in case he hit me.’ So Paul hovered shyly. The group then transferred to the church hall, where they were booked to play another set later. After a while Paul felt bold enough to ask John if he might have a go on his guitar.

Armed with the guitar, he grew bolder still. First, he asked to retune it, and then he launched into various songs, among them ‘Twenty Flight Rock’ and ‘Be-Bop-a-Lula’. ‘It was uncanny,’ recalled another Quarryman, Eric Griffiths. ‘He had such confidence, he gave a performance. It was so natural.’

Ever more confident, Paul moved to the piano, and struck up a medley of Little Richard songs. John, too, was obsessed by Little Richard – when he first heard him singing ‘Long Tall Sally’, ‘It was so great I couldn’t speak.’ And now here before him, a year later, was this kid who could holler just like his idol.

‘WoooOOOOOOOOOOOO!’

‘I half thought to myself, “He’s as good as me,”’ said John, looking back on that singular moment. ‘Now, I thought, if I take him on, what will happen? It went through my head that I’d have to keep him in line if I let him join. But he was good, so he was worth having. He also looked like Elvis.’

Another band member recalled the two of them circling each other ‘like cats’. After a while Paul and Ivan drifted off home; the Quarrymen had another set to play.

Later, John asked his best friend Pete Shotton, who played washboard, what he thought of Paul. Pete said he liked him.

‘So what would you think about having Paul in the group, then?’

‘It’s OK with me.’

Two weeks later, Paul was riding his bicycle when he spotted Pete Shotton walking along. He stopped to chat.

‘By the way,’ said Pete, ‘I’ve been talking with John about it, and … we thought maybe you’d like to join the group.’

According to Pete, a minute ticked by while Paul pretended to give the matter careful thought.

‘Oh, all right,’ he replied with a shrug; and with that he cycled off home.

Everyone has a different version of this first meeting between John and Paul. No two accounts are the same. Some say they met in the hut, others in the hall; some are convinced Aunt Mimi was present, others are equally convinced she was not; of those who say she was, some think she enjoyed the concert, while others remember her tut-tutting all the way through. In 1967 Pete Shotton told the Beatles’ first biographer, Hunter Davies, that he couldn’t remember Paul making much of an impression on anyone: ‘He seemed very quiet.’ But sixteen years later, when he came to write his autobiography, his memory had changed: ‘John was immediately impressed by what he heard and saw.’

6

Back on the National Trust minibus, we were now on our way to Mendips, where John Lennon lived with his Aunt Mimi. The custodian of Mendips is Colin, who is, as it happens, married to Sylvia. He used to teach English and history, and had retired to Derbyshire. But in 2003 he answered an advertisement for a guide for Mendips, and he has been there ever since.

While I was on the bus between the two houses I worried that Sylvia might have phoned Colin to warn him of trouble ahead, but he appeared unruffled as he welcomed us to the front garden of Mendips. ‘Also, welcome from Yoko Ono Lennon. It was Yoko who bought the house in 2002 and then immediately donated it to the National Trust … I hope you enjoy an insight into the formative years of John.’

He pointed to the blue plaque on the front of the house:

The National Trust Photolibrary/Alamy Stock Photo

‘You may have noticed there is no blue plaque on Paul’s home. This is because you have to be twenty years dead before they give you a plaque.

‘In your mind’s eye, remember Paul’s home. Well, this house was built in 1933. Paul’s was twenty years younger. It was rented, not owned, what they used to call “social housing” – to live here, you would have to have been working class. John’s house was in one of the most sought-after neighbourhoods. Lawyers, doctors, bankers lived here. So he was the middle-class Beatle.

‘Our researches show that its first owner was Mr Harrap, a banker, and we believe it was his family which called it “Mendips”. These are the original windows – it has never been double-glazed. In 1938 George and Mary Smith bought the house; Mary’s nephew John came to live with them in 1945. He was raised as an only child.