One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time

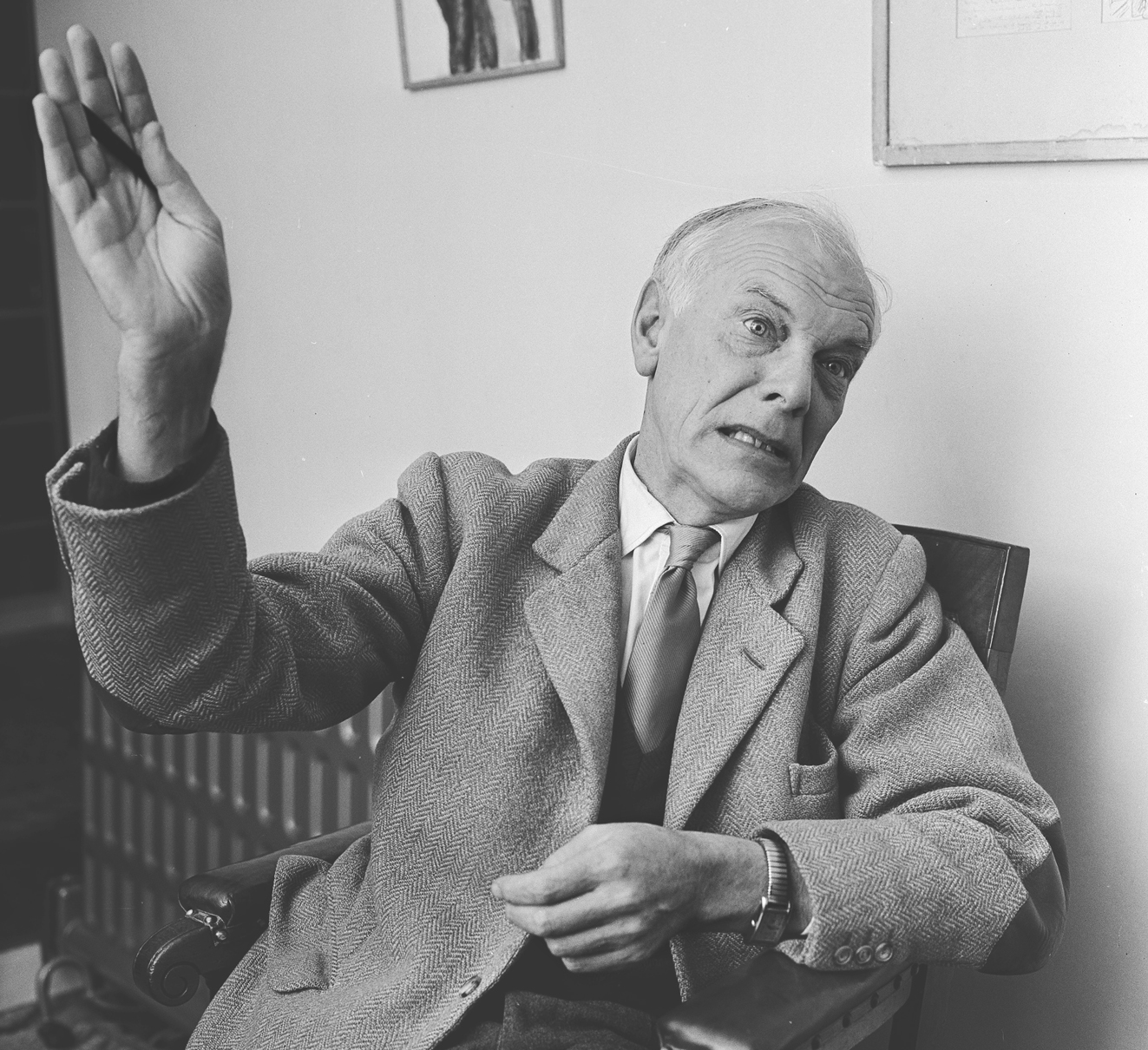

Having visited the offices of Stern magazine, Muggeridge went out on the town. True to character, he took relish in finding it ‘singularly joyless; Germans with stony faces wandering up and down, uniformed touts offering total nakedness, three Negresses and other attractions, including female wrestlers. Not many takers, it seemed, on a warm Tuesday evening.’

Popperfoto/Getty Images

On a whim, he dropped into the Top Ten Club on the Reeperbahn, ‘a teenage rock-and-roll joint’. A band was playing: ‘ageless children, sexes indistinguishable, tight-trousered, stamping about, only the smell of sweat intimating animality’. They turned out to be English, and from Liverpool: ‘Long-haired; weird feminine faces; bashing their instruments, and emitting nerveless sounds into microphones.’

As they came offstage, they recognised Muggeridge from the television, and started talking to him. One of them asked him if it was true he was a Communist. No, he replied; he was just in opposition. ‘He nodded understandingly,’ observed Muggeridge, ‘in opposition himself in a way.’

‘“You make money out of it?” he went on. I admitted that this was so. He, too, made money. He hoped to take back £200 to Liverpool.’

They parted on good terms. ‘In conversation rather touching in a way,’ Muggeridge recorded in his diary, ‘their faces like Renaissance carvings of saints or Blessed Virgins.’

13

Postcards from Hamburg

i

16 August 1960

George is just seventeen years old when he climbs into the cream and green Austin van owned by the band’s tubby Welsh manager, Allan Williams. He holds a tin of scones baked by his mother. Before watching her son set off, Mrs Harrison takes Williams to one side. ‘Look after him,’ she says.

None of the Beatles has ever been abroad. Jim McCartney entertains misgivings, but doesn’t feel he can stand in Paul’s way. The contract they have just signed gives them 210 deutschmarks a week, or £17.10s; the average weekly wage in Britain is £14. ‘He’s being offered as much money as I make a week. How can I tell him not to go?’

ii

The van is packed with a motley crew. George sits in the back with the other Beatles. Allan Williams is at the wheel, with his Chinese wife Beryl and Beryl’s brother Barry sitting next to him. Also on board are Williams’s business partner, ‘Lord Woodbine’, so-called in homage to his devotion to Woodbine cigarettes, and George Sterner, the second-in-command to Bruno Koschmider, the German club-owner with whom the boys have signed a contract.

iii

It’s the start of a long journey. There is a five-hour wait at Newhaven, and four hours at Hook of Holland while Williams insists that the Beatles don’t require permits and visas because they are students. They stop off in Amsterdam for a short break. John seizes the opportunity to shoplift two pieces of jewellery, several guitar strings, a couple of handkerchiefs and a harmonica. In his managerial role, Williams orders him to return them to the shops, but John refuses.

iv

As they drive through Germany, they sing songs – ‘Rock Around the Clock’, ‘Maggie May’ – but when they arrive at the Reeperbahn they are momentarily struck dumb, dazzled by so much neon, and so many open doors through which women can be glimpsed taking their clothes off. But they soon regain their natural ebullience, shouting ‘Here come the scousers!’ at the top of their voices.

v

Off the Reeperbahn runs Grosse Freiheit. The lights of the strip clubs are being switched on as they arrive, and the prostitutes are beginning to emerge. Still at the wheel, Allan Williams notes that the streets are ‘swarming with all the rag-tag and bob-tail of human existence – dope fiends, pimps, hustlers for strip clubs and clip-joints, gangsters, musicians, transvestites, plain ordinary homosexuals, dirty old men, dirty young men, women looking for women’.

vi

Nevertheless, it seems like a dream destination for a band whose achievements in their homeland have bordered on the pitiful. In the autumn they failed to qualify for the talent show TV Star Search; in the first three months of this year they had no professional engagements at all; in May they failed an audition to be Billy Fury’s backing group. So things are looking up. The people of Hamburg are bored by the lifeless efforts of their home-grown groups: Williams says Germans turn rock’n’roll into a death march. But British bands who have played in Hamburg – Dave Lee and the Staggerlees from Kent, the Shades Five from Kidderminster, the Billions from Worcestershire – have never looked back. The Germans seem to love them all, good, bad and indifferent.

vii

The Beatles are met at the Indra Club by Bruno Koschmider, an unprepossessing manager of an unprepossessing venue, cramped and clammy, with just two customers at the bar. Koschmider shows them to their lodgings. They haven’t been expecting much, but what they see confounds even their most meagre expectations. Between the five of them, they are expected to occupy two dark, dank, tiny rooms around the back of Koschmider’s grubby cinema, the Bambi Kino. There are no lightbulbs: they will have to make do with matches. The walls are concrete. The first room measures five feet by six. It is furnished with an army-surplus bunk bed and a threadbare couch.

viii

‘What the fucking hell!’ says John, more used to Aunt Mimi’s cosy interior décor. ‘Fuck me!’ chorus the others. ‘Only temporary,’ Koschmider reassures them; but he is lying.

This first bedroom is to be shared by John, Stu and George. John and Stu bag the bunk. George, being the youngest, has to make do with the couch.

The second bedroom is exactly the same size, but without a window. There is no means of telling if it is night or day. There are few blankets, and no heating.

Their rooms are a hair’s breadth from being en-suite, because the wall is paper thin, and on the other side is a toilet, also used by customers of the cinema. The smells seep through into their rooms.

They have to wash and shave with the cold water from the basin next to the public urinals. George never has a bath or a shower during either of his first two seasons in Hamburg.

ix

It’s all a far cry from Las Vegas. Understandably, their natural high spirits are deflated. Their first performance at the Indra is lacklustre. They stand still and chug their way through cover versions of popular hits, while half a dozen punters look glumly on. Koschmider is unimpressed. He hired the Beatles to provide energy; instead they just stand around looking woebegone.

‘Mach Schau, boys! Mach Schau!’ he demands. Make show! Make show! It does the trick, and becomes the catalyst for any amount of japes: from now on, the Beatles go all-out to enjoy themselves, strutting and dancing and screaming, hurling abuse at the audience and fighting among themselves.

x

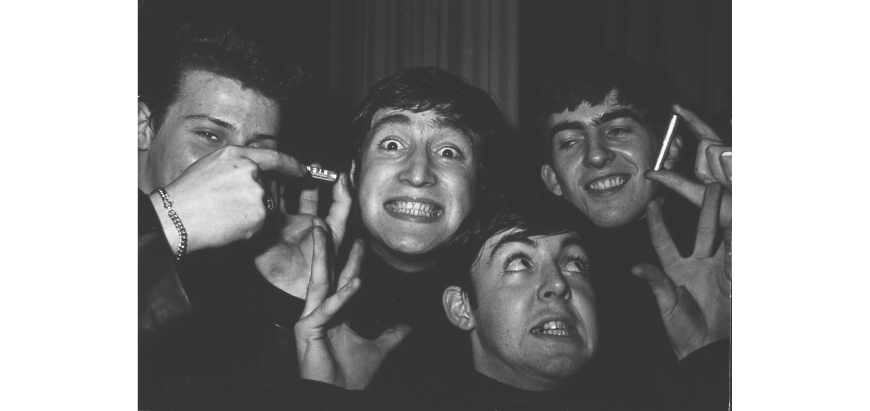

They regularly play the same song for ten or twenty minutes at a time, just for the hell of it. One night, for a bet, they play a single song – ‘What’d I Say’, by Ray Charles – for over an hour. While the others rag about, Pete remains sombre, drumming as though it were a chore, a bit like washing up.

K & K Ulf Kruger OHG/Getty Images

xi

Pete is also the only one who refuses stimulants. The others are helped in their high-jinks by a smorgasbord of cheap drugs – Purple Hearts and Black Bombers and Preludin, a slimming pill with an active ingredient1 that charges up the metabolism, keeps you wide awake and ensures that you never stop talking. Stu’s German girlfriend Astrid Kirchherr is blessed with an in-house supplier: her mother. ‘They were fifty pfennigs each and my mummy used to get them for us from the chemist. You had to have a prescription for them, but my mummy knew someone at the chemist.’ In time, they toss them back like Smarties, with beer chasers. They even talk of eating ‘Prellie sandwiches’.

xii

Unsurprisingly, it is John who pops the poppermost, and to the greatest effect, yelling obscenities, rolling around on the stage, throwing food at other band members, pretending to be a hunchback, jumping on Paul’s back, hurling himself into the audience, delighting in calling them ‘fucking Krauts’ or ‘Nazis’ or ‘German spassies’.

Diplomacy has never come naturally to him. One night he takes to the stage wearing nothing but his underpants, with a loo seat around his head, marching around with a broom in his hand, chanting ‘Sieg heil! Sieg heil!’ On another, he appears in swimming trunks. Halfway through ‘Long Tall Sally’ he turns his back to the audience and pulls the trunks down, wiggling his bare bottom at the audience. Unversed in Liverpudlian manners, the Germans applaud politely.

xiii

Cynthia comes to Hamburg on a visit, and witnesses John so out of his mind on pills and alcohol that he falls about the stage in ‘hysterical convulsions’. Offstage, he can be equally feral. He urinates from a balcony onto a group of nuns in the street below. Not that the others are models of sobriety: between numbers, Paul says something rude about Stu’s beautiful girlfriend Astrid, who all the band fancy, and Stu duly punches him. Paul fights back, and before long they are grappling onstage in what Paul comes to remember as ‘a sort of death grip’. But – Mach Schau! Mach Schau! – these spectacles prove popular. They begin to be known locally as the benakked Beatles – the crazy Beatles.

xiv

Hamburg audiences prefer to pick fights with each other, rather than with the band. The waiters – hired from the Hamburg Boxing Academy, so rusty on matters of etiquette – wear heavy boots, suitable for energetic kicking, and carry spring-loaded truncheons in the backs of their trousers, discreetly hidden beneath their jackets. Clubs keep tear-gas guns behind their counters, for use when a skirmish threatens to expand into a riot. In time, the Beatles are allotted the prefectorial duty of making the nightly announcement in German of a ten o’clock curfew for the under-eighteens: ‘Es ist zweiundzwanzig Uhr. Wir mussen jetzt Ausweiskontrolle machen. Alle Jugendlichen unter achtzehn Jahren mussen dieses Lokal verlassen.’2

xv

Bruno Koschmider is no jolly, thigh-slapping Mein Host. Kosch by name, Kosch by nature: he patrols his club brandishing the knotted leg of a hardwood German chair. If a customer proves unruly, or is too noisily dissatisfied, he will be bundled into Koschmider’s office, pinned to the floor, and beaten black and blue with it.

xvi

In the early hours of the morning, Koschmider’s fellow club-owners drop by for a nightcap. They like to send trays of schnapps up to the band, to be downed – ‘Beng, beng – ja! Proost!’ – in one. They think it hilarious that this band from England is called the Beatles, which they pronounce ‘Peadles’, German slang for ‘little willies’. ‘Oh, zee Peadles! Ha ha ha!’

xvii

The band’s japes are not confined to the stage. One afternoon they dare Paul to don a Pickelhaube and goose-step up and down the Reeperbahn with a broom for a rifle, while they yell ‘Sieg heil!’ They also enjoy playing leapfrog in the street. These fun and games prove infectious: Pete Best remembers passers-by joining in, forming ‘a long trail of Germans of varying ages all leapfrogging behind us … At some intersections, friendly cops would hold up the traffic to wave us through.’

xviii

In the heart of the Reeperbahn, sex – ‘almost limitless sex’, in Pete’s words – is freely available. ‘How could we possibly invite a dame to our squalid digs alongside the cinema urinals, dark and damp as a sewer and about as attractive?’ Pete asks, decades later, and then answers his own question. ‘But we did, and not one girl ever said no.’

George Harrison loses his virginity at the Bambi Kino, while Paul, John and Pete look on. ‘They couldn’t really see anything because I was under the covers … After I’d finished they all applauded and cheered. At least they kept quiet whilst I was doing it.’

In these conditions, nothing is private. A fan from Liverpool, Sue Johnston,3 receives a letter from Paul in Hamburg. He tells her that one night John ended up with ‘a stunning, exotic-looking woman, only to discover on closer inspection that she was a he’. The other Beatles found it hilarious.

Perhaps, in years to come, Pete’s description will be the subject of a question in a GCSE mathematics paper: ‘For the nightly romp there were usually five or six girls between the four of us … We found ourselves having two or three girls a night each … the most memorable night of love in our dowdy billet was when eight birds gathered there to do the Beatles a favour. They managed to swap with all four of us – twice!’ Many of the girls are prostitutes from Herbertstrasse, happy to waive their usual fees for these boisterous young Englishmen. Pete will never forget them: ‘I still remember some of their names: Greta, Griselda, Hilde, Betsy, Ruth … The Beatles’ first groupies.’

xix

John is as avid as any of them, but, characteristically, will recall those days of sexual wonder with a mixture of disgust and disappointment.

‘I used to dream that it would be great if you could just click your fingers and they would strip off and be ready for me,’ he will tell Alistair Taylor. ‘I would spend most of my teenage years fantasising about having this kind of power over women. The weird thing is, when the fantasies came true, they were not nearly so much fun. One of my most frequent dreams was seducing two girls together, or even a mother and daughter. This happened in Hamburg a couple of times and the first time it was sensational. The second time it got to feel like I was giving a performance. The more women I had, the more that buzz would turn into a horrible feeling of rejection and revulsion.’

xx

Equally characteristically, Paul will look back on these sexual adventures largely in terms of self-advancement. ‘It was a sexual awakening for us,’ he tells Barry Miles in 1997. ‘We didn’t have much practical knowledge till we went to Hamburg. Of course, it was striptease girls and hookers … But it was all good practice, I suppose … So we came back from there reasonably initiated. It wasn’t so much that we were experts, but that we were more expert than other people who hadn’t had that opportunity.’

1 Phenmetrazine.

2 ‘It is twenty-two hours. We must now make a passport control. All youth under eighteen years must now leave this club.’

3 At that time she was going out with Norman Kuhlke, drummer with the Swinging Blue Jeans. She later worked as a tax inspector, and then for Brian Epstein, before embarking on a successful acting career. In 2000 she received a BAFTA for Best TV Comedy Actress.

14

We assemble by the Star-Club, or where the Star-Club used to be, before it was reduced to cinders in 1983. A tall black sign, like a shiny gravestone, announces ‘Star-Club’ in diagonal writing, with a picture of an electric guitar below. Beneath the guitar sits a scattering of names from long ago, each set at a jaunty angle, and in a different typeface: ‘The Liverbirds Ray Charles The Pretty Things Gene Vincent Bo Diddley Remo Four Bill Haley King Size Taylor and the Dominoes Screaming Lord Sutch Little Richard Johnny Kidd and the Pirates Gerry and the Pacemakers The Rattles The Searchers Brenda Lee The V.I.P.s The Walker Brothers Ian and the Zodiacs Jerry Lee Lewis Tony Sheridan Chubby Checker Roy Young The Lords’.

And there, in the top left-hand corner: ‘The Beatles’.

‘OK, ze bend voss 300 days in Hemburg. Ze Feb Four in Hemburg only four weeks all other time we hev Pete Best on drums, 60–61 with Stuart, Stuart left ze bend 61 goes to art school dies April 62 in Hemburg 61 Paul change vrom guitar to bass.’

Our tour guide is Peter, a wiry, chain-smoking man in his seventies, his sparse grey hair bound in a ponytail. He rattles through the events and dates at breakneck speed, as though it were a summary of a summary, something he has recited hundreds of times before. Which, of course, he has: he has been guiding the same tour four days a week since 1970.

‘Star-Club close 69, then ve hev cabaret for surteen years, in 83 everyzing burned down. One building was at ze front so they rebuild ze back one and where we hed the hall in sixties is beckyard today. Peadles play here April May then November and December 62.’

He has only been going a few minutes, but we are already finding it hard to keep up. It reminds me of a maths lesson, or perhaps a history lesson about the Wars of the Roses, a great jumble of dates and locations.

‘Top ect in April, six weeks to May voss menly Gene Wincent, but November Little Richard and December Johnny and ze Hurricanes. Peadles voss one of only four or five bends mostly supporting ze top ects.’

Every now and then he recites an anecdote, but they come unexpectedly, and are often hard to decipher.

‘In Germany ve hev Tony Sheridan and the Beat Brothers on “My Bonny” but in England it voss Tony Sheridan and ze Peadles so nobody know Peadles voss sem bend as Tony Sheridan!!!! See some guys, I zink who is zeez guys? I think who is deez English rockers? I sink, oh, shit, voss ze Peadles!!!!!’

We do our best to smile in the right place. Peter leads us into a dingy courtyard, full of litter, and hands around a postcard-sized black-and-white photograph of what it used to look like. It seems to have been just as dingy, but entirely different.

‘Dis is picture after ze fire. Here voss stage, here voss hall, stage left to right five metres. Voss a really goot fire!’

We pass the postcard around. Each of us gazes at it, then at the present-day scene, then at the postcard again, as if attempting to work out a puzzle. But nothing fits.

‘Here voss zree steps, vun doo zree.’

We look down, pretending to spot three steps. ‘OK, you hev your pictures here.’ One or two people take photographs of where the three steps would be, were they here, which they aren’t.

Peter walks on, and we tag along behind him. As he walks, he zips through another personal anecdote.

‘I met John 66, in leather store on Reeperbahn. Zey buy cowboy boots, leather jackets and I voz in ze store when he mek the movie How I Von dur Var, I talk to him for ten minutes.’

Someone asks what they talked about.

‘So long ago I cannot remember zet von.’

He rushes on, racing through all the bands that played in Hamburg, back in the day.

‘OK, so dur sixties was so amezin. Ve hev Jaybirds, voss complete line-up of Ten Years After. Ve hev dur Small Faces. Ten weeks later ve hev Eric Clepton and dur Cream. Ve hev bend called Mendrake Root vit Ritchie Blackmore zey become Deep Purple. Ve hed really goot bend called Ze Earth. On ze vay beck zey change name to Bleck Sabbath. Six months later ve hed Jimi Hendrix here. 6 March 1967 Hendrix play zree days here, Friday, Seturday, Sunday March 67. On ze Monday morning Jimi buy Fender Stratocaster, cost about eleven hundred. On Thursday, he play Monterey, he burn down ze new Stratocaster he buy in Hemburg. He hed not planned to burn down guitar but Ze Who kicked down zeir drums, yeah? So he thought, “Vot cen I do?”

‘Now ve go Reeperbahn district.’

We walk towards the end of the street. On the way, he talks about the sort of people who come on his Beatles tours. ‘Most English people. Most German not zo interested, maybe older people from East Germany. Ozzervise, Spain, Jepen, South Emerica. Hemburg people is not interested in Peadles. We have Peadlemania museum but after three years it closed. Now, all zey vont is Sex and Crime tours.’

He retains fond memories of the Beatlemania museum. It stretched across five floors, he says, but the exhibits consisted mainly of reproductions of the original items, rather than the items themselves. ‘Only original voss contract from Bert Kaempfert with the Peadles, ze rest voss not original. Not original guitars, not original drums. But fifth floor zey hev original signs from ze Star-Club, Indra, all ze signs from the streets. Voss really good museum but not popular enough. I talk to zo many Hemburg people hev not been zere.’

We arrive at a circular paved area, where the street joins the Reeperbahn. It is called Beatles-Platz. Aluminium silhouettes of four figures with guitars and another on drums stand at one edge of the circle, looking rather like outsize pastry-cutters.

‘Zis is ze line-up from 1960. We hev John, George, Paul, Pete and there’s Stuart on ze right-hend side. On drums is Pete Best, not Ringo.’

He looks disconsolately at the circular area. It’s draughty and lacklustre, as unglamorous as can be.

‘I don’t like zis place but is better zan nothing. We hev it about ten years. You see, it is record label.’ We look again, and I can just about make out what he is getting at: in the centre of the circle is a smaller circle, in lighter stone, which could be the label of a giant LP, and two or three metal grooves run around what would be the disc itself, with various Beatles song titles written on them. It’s all a bit makeshift.

Someone asks if Pete Best ever comes back. Of all the hundreds of names associated with the Beatles, his is the one that can still darken the atmosphere. ‘Pete Best voss in Hamburg four five times, I see him many times, zum people say Pete he’s earned nothing but, wideos, dee-wee-dees, they give him lot of money, he really heppy.’

We stare at the songs inscribed on the metal grooves, including ‘She Loves You’ and ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’. ‘In 1964 ze bend voss one veek in Paris, they record two of zeir songs in German language – “Sie Liebt Dich” und “Komm Gib Mir Deine Hand” – you cen listen on YouTube.’

We cross the Reeperbahn. A shop called Tourist Center sports a huge Union Jack as a backdrop to its window display of novelty mugs and cats, dogs and penguins with wobbly heads. I can’t spot any Beatles memorabilia, though. Apparently, this was the leather store where Peter encountered John, over half a century ago.

‘I voss in the store ven John came in 66. He voss vith ze actor Michael Crarfood and Neil Espinall.’ He brings himself up short, suddenly remembering that he has already told us about it. ‘Jimi Hendrix stayed zree days in Hemburg in small hotel, March 67. You vont to see?’

He brings out his photographs and sifts through them. One, in black and white, is of Jimi Hendrix and Chas Chandler in a German street. ‘All ze buildings are gone now. Jimi ask me, “Vare cen I find the Peadles’ places?” and we walk around. I see six concerts with Jimi in March 67. I pick him up outside ze hotel. At end, Jimi give me autograph. He vrite, “To Peter stay kool Jimi Hendrix”. Jimi gave me one of his cigarettes. It voss Kool with a K, so ze autograph says “stay kool” vith a K.’

He shows us a building where the Top 10 Club used to be, then whips through one of his hard-to-follow history lessons. ‘Zet building voss Top 10 today id is discotheque. Before Top 10 voss a hippodrome, a little bit circus, donkey or a horse walk round – that voss showbiz in the fifties! Peadles played three months first April 61 to end of June six to eight hours every day 35 deutschmarks not a lod of money.’ He points to the roof where John, George and Paul once posed for a photograph. ‘61, ze bend lived under ze roof, zey hev those rooms, one two. 61, Stuart left the bend, Paul changed vrom guitar to bass. Other bends play here – Elex Harvey, Rory Gellegher – but Top 10 Club close 88.’

There is nothing – no sign or statue or plaque – to show that this is where it once was. This makes him cross. ‘Hemburg does nothing about Top 10 Club! Nothing about Peadles!’

Also on the Reeperbahn is the police station where Paul and Pete were held overnight, accused of starting a small fire in their apartment. ‘Some say it voss con-domes on ze wall, others say it vos some sort of paper. Anyway, zey hev a fire, voss arrested, zen deported, from here ve valk to the Rock’n’Roll door, ten, fifteen minutes.’