One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time

‘Mary Smith – better known as Aunt Mimi – was known for her withering looks,’ he continued, ‘and she would cast these withering looks on the people who lived on the council estate. She’d call them “common” because they lived in social housing. And so did my mum. And that’s because Mimi was a snob, and so was my mum! They were both SNOBS!’

I was taken aback by the note of anger he had injected into the word ‘snobs’. It’s not the sort of thing one usually hears from National Trust guides as they glide proprietorially around the stately homes of England. On the whole, they are tweedy types, well-adapted to the demands of snobbery. In fact, many of them would regard Aunt Mimi as something of a role model.

Colin informed us that Aunt Mimi did not like to get her front hall dirty, so she would direct people to the back door. Apparently there is an old Liverpool saying: ‘Go round the back and save the carpet.’

‘Paul said to me, “I arrived with a guitar on my back and forgot that John had said, ‘Paul, don’t go to the front door.”’ And, for you, too, it has to be the tradesman’s entrance …’

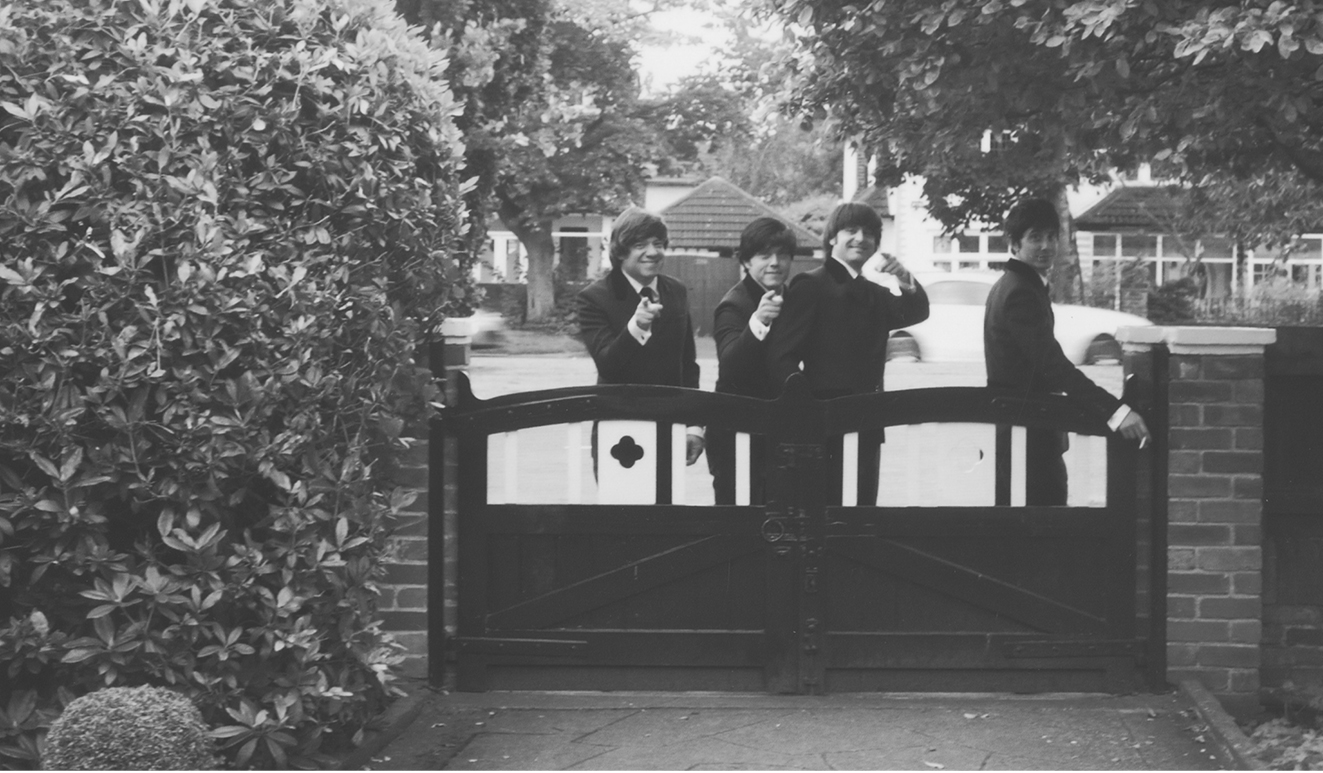

With that, Colin shepherded us into the spacious garden behind the house. While we were shuffling through, I happened to turn round. The Beatles, in their smart grey suits, circa 1964, were leaning over the front gate, pointing at me and grinning.

I took a closer look: they were not the actual Beatles, but replicants, possibly one of the looky-likey groups who had come to Liverpool for that week’s International Beatleweek Festival.

Author

Colin led us through the back door, and into the kitchen. Mimi herself renovated it in the 1960s, introducing a shiny new yellow formica worktop and a double-drainer sink, and her refitting was itself refitted by subsequent owners. But with its determination to turn back the clock, the National Trust scoured the country for the type of kitchen items that might just possibly have been in Aunt Mimi’s house back then: large jars of pickled onions, tins of baking powder and condensed milk, a bread bin with ‘BREAD’ on it, a wooden cutting board, PG Tips, Rinzo, Olive Green household soap, a –

‘Are you taking notes?’

I looked up. Colin had stopped his spiel and was pointing at me.

‘Are you taking notes? Because a lot of what I am talking about is private information.’

Once again I felt as if I had been caught shoplifting, and immediately turned defensive. How could it be private information if he was relaying it to 12,000 visitors a year? He said that he had already written one book about the Beatles, and was gathering material for another. He clearly wanted to ring-fence some of this information for himself. Yet so far he hadn’t said anything that I hadn’t read countless times.

‘Well,’ I said, attempting a conciliatory tone, ‘tell me when there’s something you don’t want me to mention and I won’t write it down.’

‘OK,’ he said. ‘I don’t want you to include anything I say from now on.’

This didn’t seem fair. I had, after all, paid my £31 (including guidebooks) to go round the homes of Paul and John, and at no point was I told that I couldn’t take notes. In the past I have taken notes on guided tours of Windsor Castle, Cliveden and Petworth House, and the guides have all looked on benignly.

By now I was bristling. Crammed into the little kitchen, everyone else started looking at the floor in embarrassment. It was ridiculous, I thundered, absolutely absurd: this was a public place, a National Trust tour, I had paid my way, the same restrictions didn’t apply to any other National Trust house I knew of, and so on and so on. Colin hit back, asking if I’d applied to head office for permission to take notes, and if not, why not, and what he was saying was private information, etc. etc. As our arguments became increasingly circular and tormented, some of the other visitors began drifting off into the next room, forcing Colin to interrupt himself in order to corral them back. ‘Could you please stay in this room until I tell you to go!’ he snapped.

Eventually he had no choice but to move on. Subversively, I placed myself at the back of the group and kept writing notes defiantly, but by now I had become so het up that they emerged as indecipherable squiggles. Meanwhile, Colin was prefacing even the most humdrum observations with phrases like ‘Strictly between ourselves’ and ‘Between you, me and the gatepost’.

He told us that Aunt Mimi had taken lodgers (stale buns!) because she needed extra money to send John through art school. ‘Considering she herself took in lodgers, it’s ironic she called other people common,’ he added, meanly. Once more, he called her a snob. Poor Aunt Mimi! I wondered how she would have felt in 1959 had she known that sixty years on, 12,000 visitors a year would be paying £25 a head (excluding guidebooks) to rootle around in her kitchen and be told that she was a snob.

It came as a relief when Colin suddenly announced that we could go upstairs unaccompanied. Free at last from his beady gaze, I poked my head around the door of the upstairs loo. Was this the actual seat that John himself had once sat on, or just a replica? I then went into his bedroom. Three magazine covers were stuck to the wall above the bed, each with Brigitte Bardot in an enticing pose.

Around the time when Mendips was first opened to the public, I watched a TV documentary about Yoko’s involvement in the project. She emerged as a controlling figure, stating exactly how she wanted everything to be. Nothing would stop her getting her own way. In one scene, she had even objected to the colour of John’s bedspread. ‘It was definitely not pink. You know what? I remember John telling me it was green.’

I remember thinking this was one of the most improbable things I had ever heard. But, anxious to butter Yoko up, the National Trust operatives had taken pains to assure her that, yes, of course they would see to it that the bedspread was changed. So it made me very happy to see that the bedspread is still as pink as pink can be. I desperately wanted to point this out to Colin, just to show that I was on the case, but I was fearful that he would have me arrested. Instead, I studied the framed letter from Yoko propped up on the bed. She wrote of how John was ‘always talking about Liverpool’, and how, whenever they visited the city, they would drive along Menlove Avenue, and he would point at the house and say, ‘Yoko, look, look. That’s it!’

She went on to say that all of John’s music and his ‘message of peace … germinated from John’s dreaming in his little bedroom at Mendips’. Characterising the young John as ‘a quiet, sensitive introvert who was always dreaming’, she said that he was ‘an incredible dreamer, John made those dreams come true – for himself and for the world’.

She ended by saying that walking into this bedroom today still gave her ‘goosebumps’, and hoping that for the National Trust visitor it will ‘make your dream come true, too’.

Every year, more pop stars pass from rebellion into heritage. In Bloomsbury, I live in a block of flats which bears a plaque saying that

ROBERT NESTA

MARLEY

1945–1981

SINGER, LYRICIST AND

RASTAFARIAN ICON

LIVED HERE

1972

Elsewhere in London there are plaques of one sort or another to, among many others, Jimi Hendrix, Tommy Steele, Dire Straits, Pink Floyd, the Small Faces, Don Arden, Spandau Ballet and the Bee Gees.

It turns out that Bob Dylan is an enthusiast for visiting sites associated with rock stars. In 2009 he visited Mendips, and was overheard saying, ‘This kitchen, it’s just like my mom’s.’ David Kinney, author of The Dylanologists, notes that Dylan has also visited Neil Young’s childhood home in Winnipeg, as well as Sun Studios in Memphis, where he took the trouble to kneel down and kiss the spot where Elvis Presley first sang ‘That’s All Right’. Apparently, as Dylan left the studios, a man chased after him and told him how much he loved him. ‘Well, son, we all have our heroes,’ he replied.

Dylan’s own hometown of Hibbing, Minnesota, now offers tours of his old family synagogue, his old school, his old house and the hotel where he had his bar mitzvah. The menu of a Dylan-themed bar called Zimmy’s offers Hard Rain Hamburger, Slow Train Pizza, and Simple Twist of Sirloin.

7

Something deeper than music linked John and Paul. Their mothers had died when they were in adolescence: Paul’s when he was fourteen, John’s when he was seventeen.

When he first met John, Paul had already lost his mother, but John’s mother, Julia, was still alive. ‘His mother lived right near where I lived. I had lost my mum, that’s one thing, but for your mum to actually be living somewhere else and for you to be a teenage boy and not living with her is very sad. It’s horrible. I remember him not liking it at all.’

Paul recalled ‘a tinge of sadness’ in John at being apart from Julia. ‘She was a beautiful woman with long red hair. She was fun-loving and musical too; she taught him banjo chords, and any woman in those days who played a banjo was a special, artistic person … John and I were both in love with his mum. It knocked him for six when she died.’

It created a bond between them. Together, the two boys conspired to upend their grief, to turn the wound into a weapon. ‘Once or twice when someone said, “Is your mother gonna come?” we’d say, in a sad voice, “She died.” We actually used to put people through that. We could look at each other and know.’

There was something more peculiar that linked them, too. In 1997 Paul told his friend and biographer Barry Miles, ‘At night there was one moment when she would pass our bedroom door in underwear, which was the only time I would ever see that, and I used to get sexually aroused. I mean, it never went beyond that but I was quite proud of it, I thought, “That’s pretty good.” It’s not everyone’s mum that’s got the power to arouse.’

One afternoon John ventured into his mother’s bedroom. Julia was taking a nap in a black angora sweater, over a tight dark-green-and-yellow mottled shirt. He remembered it exactly. He lay on the bed next to her, and happened to touch one of her breasts. It was a moment he would replay over and over again in his memory for the rest of his life: ‘I was wondering if I should do anything else. It was a strange moment because at the time I had the hots, as they say, for a rather lower-class female who lived on the opposite side of the road. I always think I should have done it. Presumably, she would have allowed it.’

John’s friends remember Julia as vivacious and flirtatious. The first time Pete Shotton met her, he found himself ‘greeted with squeals of girlish laughter by a slim, attractive woman dancing through the doorway with a pair of old woollen knickers wrapped around her head’. John introduced him. ‘Oh, this is Pete, is it? John’s told me so much about you.’ Pete held out his hand, but she bypassed it. ‘Julia began stroking my hips. “Ooh, what lovely slim hips you have,” she giggled.’

Twenty-four years later, in 1979, sitting in his apartment in the Dakota Building, John recorded a cassette tape. At the start he announced, ‘Tape one in the ongoing life story of John Winston Ono Lennon.’ After rushing through a variety of topics – his grandparents’ house in Newcastle Road, Bob Dylan’s recent Christian album Long Train Coming (‘pathetic … just embarrassing’), his love of the sound of the bagpipes at the Edinburgh Military Tattoo when he was a child – he returned, once more, to that recurring memory of the afternoon he lay on his mother’s bed and touched her breast.

On The White Album,1 the song ‘Julia’ sounds less like an elegy than a love song, full of yearning for someone unobtainable:

Julia, sleeping sand, silent cloud, touch me

So I sing a song of love – Julia.

1 Officially titled The Beatles, it became popularly known as ‘The White Album’, or occasionally ‘The Double White’, but never ‘The Beatles’. For the rest of this book I will call it The White Album.

8

Julia’s shifty forty-one-year-old boyfriend Bobby Dykins – ‘a little waiter with a nervous cough and thinning margarine-coated hair’, in John’s words – had lost his driving licence, and his job. Driving drunk along Menlove Avenue at midnight, his erratic movements were clocked by a policeman, who signalled him to stop. But Dykins kept going, turning left when he should have turned right, then mounting the reservation. Asked to get out of the car, he fell to the ground and had to be helped to his feet. The policeman informed him he was under arrest, and made a note of his response: ‘You fucking fool, you can’t do this to me, I’m the press!’

Dykins was held overnight in a cell, taken to court the next morning, and then released on bail. A fortnight later, on 1 July 1958, he was disqualified from driving for a year and fined £25 – roughly three weeks’ wages – plus costs.

Dykins decided that cuts to the household budget were in order; he centred them on the seventeen-year-old John. They could, he said, no longer afford his rapacious appetite; he would have to stay with Julia’s sister Mimi. On Tuesday, 15 July, Julia popped round to Menlove Avenue to tell Mimi of these new developments.

Having sorted things out with Mimi, Julia set off for home at 9.45 p.m. Sometimes she would walk across the golf course, but on this occasion she opted for the no. 4 bus, due in a couple of minutes, a hundred yards along on the other side of the road.

As Julia was leaving, John’s friend Nigel Walley dropped by, but Mimi told him John was out.

‘Oh, Nigel, you’ve arrived just in time to escort me to the bus stop,’ said Julia. Nigel walked her to Vale Road, where they said goodbye, and he turned off. As Julia crossed Menlove Avenue, Nigel heard ‘a car skidding and a thump and I turned to see her body flying through the air’. He rushed over. ‘It wasn’t a gory mess but she must have had severe internal injuries. To my mind, she’d been killed instantly. I can still see her gingery hair fluttering in the breeze, blowing across her face.’

The impact of his mother’s death on John was immediate. ‘I know what a terrible effect it had on John,’ Nigel said, decades later. ‘He felt so lonely after it. His outlook changed completely. He hardened and his humour became more weird.’ For months, John refused to speak to him. ‘Inwardly, he was blaming me for the death. You know – “If Nige hadn’t walked her to the bus stop, or if he’d have kept her occupied another five minutes, it would never have happened.”’

9

It is June 1957. Paul is a bright grammar-school boy; he has been encouraged to take two of his GCE O-Level exams – Spanish and Latin – a year early.

His father, Jim, keeps pointing out that it’s not possible to do your homework and watch television at the same time. Paul argues that it makes no difference. His good marks at the Liverpool Institute seem to support this view. But in truth, his mind is on other things. All he wants to do is play records with his friend Ian James. The two of them go from record shop to record shop. Sometimes they play their guitars together. Revision takes a back seat.

At the end of August Paul’s GCE results come through.

(a)

He has passed Spanish, but failed Latin. This means he will not be able to go up a year, as planned. Instead he must remain in the Remove, alongside boys a year younger. Jim is upset. He thinks Paul failed Latin deliberately, because he didn’t want to go to university. Paul is also upset. When he goes back to school in September, he hates being in classes with his juniors.

Paul is now in the same year as a little boy he recognises from the bus as a fellow smoker. When he was in the year above, he never really spoke to him. But now that they are in the same year, the two grow close. The boy is called George Harrison.

From the heights of the Lower Sixth, Paul’s friend Ian James is baffled by the burgeoning friendship. To him, they have totally different personalities: ‘George always seemed a bit moody, morose, whereas Paul was light-hearted – he probably could have been a comedian if he’d wanted, he can tell a tale so well. George was nothing like that. I found it really strange that they were friends.’

Paul is impressed by George’s guitar-playing, and introduces him to John Lennon, who is seventeen and no longer at school. John doesn’t want to be seen socialising with a fourteen-year-old. He is irritated by the way Little George, as he is known, follows him ‘like a bloody kid, hanging round all the time’.

But one day, when John is on the same double-decker, Paul seizes the opportunity to get George into their new band. On the upper deck, Paul tells George to play the song ‘Raunchy’. ‘Go on, George, show him!’ Little George, as they all call him, takes his guitar out of its case and starts to play. John is impressed. ‘He’s in, you’re in, that’s it!’ The audition is over.

(b)

He has passed both Spanish and Latin. This means he goes up a year, joining the Lower Sixth with his best friend Ian James. Now and then he sees George Harrison in the school corridors, but Little George is in the year below, and anyway, they don’t have much in common. George and Paul occasionally bump into each other on the bus, but there is no reason why Paul would ever introduce him to John; so he never does.

10

On 21 May 1956, Léo Valentin, the Frenchman known as ‘Birdman’ and billed as ‘The Most Daring Man in the World’, was crouched in a plane above Liverpool Speke Airport. The author of Je suis un homme-oiseau was preparing to leap out wearing wings made from balsawood and alloy. He planned to retire after this one last leap: the £200 he was set to earn from the Liverpool Air Show would help fund his dream of owning a provincial cinema back in France.

‘To see a man fling himself into space …’ he once wrote. ‘It is a mad action. You want to turn away, but you are fascinated, watching the man who takes pleasure in taunting death.’

An estimated 100,000 spectators were gathered on the airfield below; George Harrison, aged thirteen, and Paul McCartney, just shy of his fourteenth birthday, had cycled there together.

The two boys watched as Valentin hurled himself from the back of the plane. But as he leapt, one of his wings splintered against the plane’s door frame. ‘We watched him drop and went, “Uh-oh … I don’t think that’s right,”’ recalled Paul.

Valentin spun around and around, out of control. His parachute failed to open, and then his backup parachute wrapped around him, like a shroud. This made it easier for the crowd below to see the plummeting figure.

‘We thought, “Any second now his parachute’s gonna open,” and it never did. We went, “I don’t think he’s going to survive that.” And he didn’t.’

Valentin fell to the ground in a cornfield, ‘spreadeagled like a bird’, in the words of one spectator.

In 1964, John Lennon advised the Beatles’ press officer, Derek Taylor, against eating the cheese sandwiches at Speke Airport. He had once been employed at Speke as a packer, he told him, and he used to spit in them.

In spring 2002, Speke Airport was renamed Liverpool John Lennon Airport. Along with John F. Kennedy, Leonardo da Vinci and Josef Strauss, John Lennon is one of very few people to have an airport named after them. A seven-foot-high statue of John overlooks the check-in hall, and a vast Yellow Submarine stands on a traffic island at the entrance. The airport’s motto is taken from his song ‘Imagine’: ‘Above Us Only Sky’.

11

A Party:

22 Huskisson Street, Liverpool

8 May 1960

All-night parties have become so popular among art students in Liverpool that partygoers are expected to bring not just a bottle but also an egg, for breakfast.

John and his fellow Beatles band member Stu Sutcliffe have been invited to an all-night party at 22 Huskisson Street1 by one of their art-school lecturers, Austin Davies. Stu occasionally babysits for Austin and his wife Beryl, who is an actress. John brings his girlfriend Cynthia, and his bandmates Paul and George, both seventeen, tag along, uninvited. The current name of their band is the Silver Beats, but it’s still in a process of development.

The party is composed of an odd mixture of guests: in the upstairs room, musicians from the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, still in full evening dress, fresh from playing Tchaikovsky, chat with Fritz Spiegl, their principal flautist; downstairs, art students play Ray Charles’s latest single ‘What’d I Say’ over and over again on the record player.

George can’t hear enough of the song. He stands transfixed, knocking back glass after glass of wine and beer, slowly shedding his inhibitions. At one point he spots Spiegl, who has just ventured downstairs, and shouts, ‘Hey, Geraldo – got any Elvis?’

Paul is beginning to enjoy these parties. Always keen to project the right image, he has begun to favour a black turtleneck sweater and to act mysterious, like Jacques Brel. ‘It was me trying to be enigmatic, to make girls think, “Who’s that very interesting French guy over in the corner?”’ He sometimes arrives at parties with his guitar, strumming a French song, singing ‘rhurbarbe, rhubarbe’. He has composed a tune to sing along to, but for now it only has one word in French, and that just a name – ‘Michelle’.2 He can’t think of anything to rhyme with it.

The party goes on way past the next morning. Later, Beryl estimates that it lasted three days and three nights. Halfway through the first night, John and his band get carried away, and start singing loudly. Beryl thinks they make a dreadful racket. ‘They played almost for two nights. I said it was a disgusting noise. I took the children out.’ She walks them down the road to a friend’s house, and stays there herself. The next morning she returns to no. 22 to get some clothes, only to find her bedroom door locked. A partygoer tells her that her husband is in there, with a friend. ‘That night we separated. We divorced amicably. I never saw the Beatles again.’ But she harbours no grudge against the Beatles. In fact, quite the opposite. Forty-eight years later, the acclaimed novelist Dame Beryl Bainbridge talks of those early days with great affection, and picks ‘Eleanor Rigby’ as one of her Desert Island Discs.3

1 By chance, the very same house in which John’s mother Julia was living when she married Fred Lennon.

2 Five years later, when Paul and John were harvesting songs for Rubber Soul, John suddenly remembered that Paul used to sing a French song at parties. Once again, Paul struggled to think of a rhyme for ‘Michelle’. A visiting French teacher, Jan Vaughan, the wife of Paul’s old schoolmate Ivan, suggested ‘ma belle’. He then asked her to translate ‘these are words that go together well’ into French, and later sent her a cheque for her contribution. John supplied the ‘I love you, I love you, I love you’ interlude, after listening to Nina Simone’s recently released ‘I Put a Spell on You’.

3 Bainbridge’s other Desert Island Discs were characteristically eccentric, among them ‘Two Little Boys’ by Rolf Harris, ‘Kiss Me Goodnight, Sergeant Major’ by Vera Lynn and ‘Bat Out of Hell’ by Meatloaf.

12

Already well-known as a journalist and editor, and rapidly becoming a household name as a television presenter, Malcolm Muggeridge took a flight from London to Hamburg on 7 June 1961. Two months earlier, he had recorded his distaste for the medium with which he would soon be identified.

As always deeply distressed by seeing myself on television … Decided never to do it again. Something inferior, cheap, horrible about television as such: it’s a prism through which words pass, energies distorted, false. The exact converse of what is commonly believed – not a searcher out of truth and sincerity, but rather only lies and insincerity will register on it.