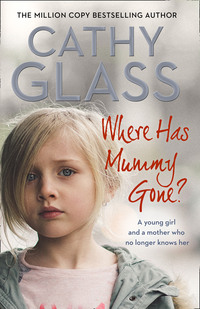

Where Has Mummy Gone?

She glanced at her list. ‘No, not yet.’

‘Mummy’s not here!’ Melody cried.

‘I am sure she will be soon,’ I said. ‘I’ll sign us in and then we can sit in the waiting room – there are toys and books in there.’

‘Why isn’t she here?’ Melody lamented as I entered our names in the Visitors’ Book.

‘I don’t know, love. Come on through here.’

‘I bet she got lost. Mum often gets lost when we have to go somewhere new. She needs me to show her.’

‘Your social worker will have told her how to get here,’ I said. ‘Try not to worry.’ The waiting room was empty and we sat on the cushioned bench.

‘What if Mum hasn’t got the money to come here on the bus?’ Melody asked.

‘Neave, your social worker, will have checked she has enough money.’ Parents of children in care are given all the help they need to get to contact, including bus or taxi fares when appropriate.

‘Mum’s not good without me,’ Melody said again.

I thought she was worrying about her mother far more than most children I’d fostered, and I was hoping that when she saw her she would be reassured that she was coping. I was also hoping Amanda wouldn’t be much longer. Her lateness, which was making Melody even more anxious, would be noted by the contact supervisor, who would now be waiting in the allocated room. I knew from experience that we wouldn’t be allowed to wait indefinitely and at some point the manager of the Family Centre would make the decision to cancel the contact and I would return home with Melody. It’s devastating for the child, but not as bad as waiting until the bitter end and having to accept the parent hasn’t come to see them. The child’s feelings of rejection at not being able to live with their parents are compounded and they feel even more unloved. Parents of children in care have to make contact a priority, which I’d have thought was obvious, but isn’t always, especially if the parents are struggling with drink and drug misuse or have mental health issues.

The minutes ticked by. I tried to distract Melody with books and games, but she just sat there clutching the box of rice pudding, listening for any sign of her mother, and asking me every few minutes what time it was. We heard the security buzzer on the main door go a few times, but it wasn’t her mother. Melody wrung her hands and worried something bad had happened to her. Then at 4.30 p.m. the centre’s manager came in and said that they’d tried to phone Amanda but there was no reply, and they’d give her until 4.45 and then they’d cancel it, unless she phoned to say she was on her way. This was more generous than usual and it was because it was the first contact. Usually if a parent doesn’t phone to say they’ve been delayed then only thirty minutes are allowed.

‘Where’s my mum got to?’ Melody asked me again after the manger had left. ‘Something really, really bad must have happened to her, I know. She needs me, it’s my fault.’ Her bottom lip trembled and her eyes filled.

‘It’s not your fault, love,’ I said, putting my arm around her shoulders. I wondered if Amanda had any idea of the pain she was causing her child.

Five minutes later we heard the security buzzer sound again and the main door open and close, followed by a thick, chesty cough.

‘That’s my mum!’ Melody cried, jumping up from her seat. ‘She’s here. Mummy!’ She ran out of the waiting room. I quickly followed her down the short corridor and into reception, where a woman I assumed to be Amanda was giving her name to the receptionist. ‘Mummy! Mummy!’ Melody cried and rushed to her.

Amanda turned and for a second seemed to look confused, as if she wasn’t sure where she was and who was calling her, then, recognizing her daughter, she opened her arms to receive her.

‘Mummy, where’ve you been? You’re late. I was going to have to go home without seeing you!’ Melody cried.

‘Over my dead body!’ Amanda snapped in a threatening tone.

Deathly pale, with a heavily lined face and sunken cheeks, Amanda was stick thin and her jeans and jumper hung on her skeletal frame. Her hair was falling out and her scalp was visible in round bald patches. She looked haggard and aged well beyond her forty-two years. If ever there was an advertisement to deter people from drink and drug abuse, it was her. I’d seen it before in the parents of children I’d fostered and would sadly see it again. She lisped as she spoke and as I went closer I saw her two front teeth were missing.

‘Hello Amanda, I’m Cathy, Melody’s foster carer,’ I said positively. ‘Pleased to meet you.’

She’d let go of her daughter and was now trying to understand what the receptionist was telling her, which was to sign the Visitors’ Book.

‘The Visitors’ Book is here,’ I said, trying to be helpful and pointing to it.

‘Come on, Mummy, you have to write your name,’ Melody said. Taking her hand, she led her mother to the book and then gave her the pen beside it to sign. I exchanged a glance with the receptionist, who was looking at her, concerned. Amanda wouldn’t be the first parent to arrive at contact under the influence of drink or drugs, although I couldn’t smell alcohol and she seemed confused rather than high or drunk. I watched as she made an illegible scrawl in the book, then, setting down the pen, she turned to her daughter.

‘Where do we go?’ she asked her.

‘You’re in Yellow Room,’ the receptionist said. ‘The manager is coming now to show you.’ It’s usual on the parent’s first visit for the manager to show the parent and child around so they know where the toilets, kitchen and rooms are. Six rooms lead off a central play area where the larger toys are kept, and each room takes its name from the colour it is painted.

‘How are you?’ I asked Amanda, trying to strike up conversation. It’s important for the child to see their carer and parent(s) getting along. Amanda looked at me, puzzled, as if she’d forgotten who I was, and I was about to remind her when the manager appeared. It was now time for me to go, as contact had started and this was Amanda’s time with her daughter.

‘When will contact end?’ I asked the manager, as we were starting late

‘Five forty-five,’ she said.

‘See you later then,’ I said to Amanda and Melody. There was no reply. I signed out, and as I left they were following the manager down the corridor and into the hub of the building.

It was dark outside now in winter, and cold. I pulled my coat closer around me and returned to my car. I usually try to put the time when a child is with their parent(s) to good use, either by doing some essential grocery shopping or by catching up on some paperwork in a local café, but now I sat in the car thinking about Amanda. I was starting to see why Melody was so worried about her. She appeared incredibly fragile and vulnerable and clearly needed Melody’s help – as she’d been telling me. The social services had been aware of the family for a while and support had been put in, so I assumed Neave knew of Amanda’s dependency on Melody. But now, having met Amanda, I wondered how the two of them had coped at all. Far from fearing Amanda at that point, I felt sorry for her. No one starts their life wanting to make a complete mess of it and lose their children and die prematurely, which surely must be Amanda’s fate.

Chapter Six

The Way Home?

Normally when I collect a child from the Family Centre at the end of contact I sign the Visitors’ Book and go through to whichever room they are in, while the parent(s) make the most of their last few minutes with their child. But now as I stepped into reception I saw that Amanda and Melody were already there, together with the manager and another woman I took to be the contact supervisor. For a moment I assumed they’d just finished contact punctually, but then I saw their expressions and knew something was wrong.

‘That’s her,’ Amanda said accusingly, jabbing her finger towards me.

‘We’ve got a few problems we need to clear up,’ the manager said, taking a step forward.

‘You bet we have!’ Amanda snarled. I could see she was chomping at the bit to get at me.

‘Amanda is very concerned about Melody’s clothes,’ the manager said evenly.

‘What about her clothes?’ I asked, immediately anxious. ‘She’s wearing her school uniform.’

‘I told you, Mum,’ Melody said, looking embarrassed.

‘Where are the clothes my daughter had on when she was taken off me yesterday?’ Amanda snapped at me, her eyes blazing. ‘You’ve stolen them.’

It was ludicrous, but they were all waiting for an answer.

‘They’re in the wash,’ I said.

‘How can I be sure she’s telling the truth?’ Amanda turned to the manager. ‘And what about her trainers?’ she demanded.

‘They’re in the car,’ I said.

‘And her hair!’ Amanda said, nudging the manager. ‘Tell her.’

‘Amanda was worried about what you put on her daughter’s hair.’

‘It’s poison,’ Amanda snapped, glaring at me.

‘Do you mean the head lice lotion?’ I asked. ‘If so, it’s a standard preparation I bought from the chemist to kill head lice. Apart from that, and shampoo and water, she’s had nothing else on her hair.’

‘She hasn’t got head lice!’ Amanda growled.

‘We couldn’t find any,’ the contact supervisor agreed.

‘No, because I treated her hair and killed them.’ I couldn’t believe how ridiculous this was, although they were all looking at me doubtfully. ‘Ask her social worker,’ I added. ‘Neave was aware that Melody had head lice.’

‘I told you I kept itching,’ Melody said to her mother.

‘And where’s her jacket?’ Amanda now demanded.

‘At home,’ I said. ‘It was badly torn, but I can return it to you if you like. The one she is wearing is a spare I had. I was going to buy her a new winter coat at the weekend. Don’t you want me to do that?’

Amanda fell silent and I struggled to hide my annoyance. The manager should have defused this situation, not turned it into a drama.

‘You mentioned her dinner?’ the supervisor now prompted Amanda.

‘What about her dinner?’ I asked. There was silence.

‘Can’t remember,’ Amanda said, and the contact supervisor had the good sense not to remind her.

‘Is that all?’ I asked curtly.

The manager nodded.

‘Say goodbye to your mother then,’ I said to Melody, who should never have heard all of this.

I was now expecting a long emotional goodbye, but Amanda suddenly said she had to go to the toilet, and shouting, ‘Bye!’ she rushed off down the corridor. I said a cool goodbye to the manager and contact supervisor and left with Melody. I was seething inside, more so with the manager and the contact supervisor than I was with Amanda. She was angry and irrational from losing her child and I was an easy target, but the manager and contact supervisor should have known better and calmed her anger instead of pandering to it and making an issue out of everything she’d complained about. Foster carers don’t expect gratitude, but a bit of moral support wouldn’t go amiss. In bending over backwards to accommodate the parents’ wishes, the staff involved in contact sometimes ingratiate themselves with the parents at the carer’s expense.

Melody didn’t say anything until we were in the car. Then, before I started the engine, she said quietly, ‘I’m sorry, Cathy.’

I turned in my seat to look at her. ‘What for, love?’

‘Mum being horrible to you. She’s like that with lots of people. She did it at school.’

‘You don’t have to apologize,’ I said. ‘It’s not your fault. Your mum is upset because you are in care. It will get easier for her each time she sees you at contact as she gets used to it. Did you have a nice time?’

‘I think so. I gave her the rice pudding.’

‘Good.’ I’d noticed Melody wasn’t carrying the stay-fresh box. ‘Did she like it?’

‘She hasn’t eaten it yet. She’s going to take it home and have it for her dinner. There’s nothing else there.’ Hearing that, all my anger evaporated and my heart went out to Amanda again. The picture of that fragile, emaciated woman, aged beyond recognition, who’d lost all her children into care, sitting alone in her cold, damp flat eating rice pudding moved and worried me. I’d telephone Jill in the morning and make sure Neave was aware of just how needy Amanda was, for when a child is taken into care the social services have a duty to help the parents where possible.

When I dished up the cottage pie that evening I set aside a portion with vegetables and gravy for Amanda. Once it had cooled, I’d put it in the freezer to take with us to contact on Friday. Melody had said there was a microwave and kettle in their flat but no cooker or hob, and I knew there was a microwave at the Family Centre. Despite Amanda’s rudeness, the woman needed help.

After dinner I left the washing up for later, and as Adrian, Lucy and Paula disappeared off to do their homework I told Melody to fetch her book bag from where she’d left it in the hall. We then sat together at the table and I helped her with her homework – reading, and spellings to learn. She needed a lot of help, but unlike some children I’d fostered who’d come from homes where education wasn’t a priority, she had the right attitude and wanted to learn. ‘Mum says you can get a good job and earn lots of money if you go to school and pass your exams.’ Which was ironic considering her mother hadn’t been sending Melody to school, but I didn’t comment.

After Melody had finished her homework I began her bath and bedtime routine, finishing with a bedtime story. She was in bed in her new pyjamas at eight o’clock. I find bedtime, when the child is tired, is when they can start fretting and worrying. Far from being reassured by seeing her mother at contact, Melody was even more anxious, as indeed I was. Now I’d met Amanda I had a better understanding and appreciation of Melody’s concerns.

‘Melody, I don’t want you to worry about your mother,’ I said. ‘Tomorrow I’m going to telephone Jill – you met her – who will speak to Neave and make sure your mother is OK.’

‘Mummy is never OK,’ Melody lamented. ‘She’s getting worse. She forgets to eat, get up and get dressed or go where she has to. That’s why she was so late.’

‘Is she still drinking alcohol or taking drugs?’ I asked her gently. ‘You know what I mean by drugs?’

‘Yes. I don’t think so. I haven’t seen her do it for a bit. The man upstairs calls her nuts, and says she’s done her head in with the stuff she put in her arm, but she can’t help it.’

‘No, all right.’ I looked at her thoughtfully. Neave had said that Amanda had been funding her drug habit from prostitution and had asked if I could find out if she’d brought clients back to their flat, which opened up the possibility that Melody had witnessed her mother with a man or, heaven forbid, had been sexually abused herself. Foster carers can’t afford to be squeamish or delicate about these matters and now seemed like a good time to ask. ‘Melody, do you know where your mummy got her money from?’

She nodded. ‘Benefits. I know because I had to help her get the money out of her bank so we could go shopping for food and pay the bills. Also she had some friends who gave her money.’

‘Did you meet any of her friends?’

She shook her head.

‘Were they women friends, do you know, or men?’

‘Men. She always said “he”.’

‘Did she ever bring her friends home to your flat?’

‘No. She always went out to meet them. She wasn’t gone long and I had to stay in the room with the door locked. On the way home she bought me a chocolate bar if she remembered. Most of our money went to the man who owned the places we lived in. Mum said we were ripped off.’

‘I understand. So Mummy never brought her men friends back to the places you lived in?’

‘No.’ Which was a relief.

‘Do you know about the private parts of our body?’ I asked, taking the opportunity to raise the matter. ‘Did your mummy ever tell you?’

‘No, but I saw it on television. In the morning there are programmes on for schools and I learnt about how babies are made, and our private parts that only we can touch.’

‘Good,’ I said. ‘So what would you do if someone tried to touch your private parts? Do you know?’

‘Scream and run away and tell an adult I trust straight away. That’s what they tell the kids at school. It was in a programme called Staying Safe.’

‘Excellent. And no one has tried to touch your private parts?’

‘No! I’d kick him in the balls if he tried.’

I nodded, although I was pretty sure that hadn’t been the exact wording used in a programme for school children! I was relieved that Melody didn’t appear to have been sexually abused, and I would let Neave know. However, Melody should never have been left repeatedly alone in a flat while Amanda met her clients – she had placed them both in danger: Melody, a young child all by herself, and Amanda working the streets. The majority of prostitutes who work the streets alone do so to fund a drug habit, and they are regularly found abused and beaten.

Once Melody was asleep I spent time with Paula, Lucy and Adrian and then I wrote up my log notes, including the conversation I’d had with Melody. After that I printed Melody’s name and class in indelible ink in all her school uniform items as the school requested, and at eleven o’clock I fell into bed. I slept well, as did Melody, and the following morning we continued the routine that would see us through the school weeks for however long Melody was with us. I woke everyone, made breakfast for Melody, Paula and myself while Adrian and Lucy – that much older – prepared whatever they fancied. Then, once ready, Melody and I left first, calling goodbye as we went.

When I returned home after taking Melody to school I telephoned Jill to update her. As my supervising social worker she was my first point of contact and we were on the phone for nearly an hour. I told her about the complaints Amanda had made about me at contact and she agreed they were irrational and felt they wouldn’t go any further. I told her what Melody had said about her mother being very forgetful and gave her examples of how she relied heavily on Melody. I said that according to Melody her mother had never brought her clients home and it seemed she hadn’t been sexually abused. Jill said she’d pass all this on to Neave. I said Melody was eating and sleeping well, was in a full school uniform (which is considered important) and was generally settling in well, apart from worrying about her mother.

‘That’s only to be expected,’ Jill said.

‘Yes, except having now met Amanda I can see why Melody is so anxious. Amanda is very needy and appears to have relied on Melody far more than I’ve seen in a parent before. She’s very forgetful and I noticed a vagueness about her, like she zones out.’

‘Drugs?’

‘I don’t know. Melody says she’s stopped using, but perhaps she’s started again.’

‘I’ll tell Neave. She can run a drugs test if necessary,’ Jill said, and winding up the conversation, we said goodbye.

I made a coffee and then returned to the phone and made appointments for Melody to have a check-up at the dentist and optician. I knew from experience that when a child first comes into care this was required. Neave would arrange for Melody to have a medical too.

At the end of school I met Miss May, the teaching assistant who was helping Melody. She accompanied Melody into the playground and to begin with she couldn’t get a word in. Melody had so much to tell me. ‘We did PE and I wore my new PE kit like everyone else,’ Melody enthused excitedly. ‘I’m good at PE, Miss May said. This is Miss May who helps me. She sits with me and the other two boys and we’ve done lots of good work today.’

Miss May laughed. ‘We have indeed. Hello, you must be Cathy.’

‘Yes, nice to meet you. Thank you for all you’re doing to help Melody.’

‘You’re welcome. She’s a delight to work with and works hard, although she has been worrying an awful lot about her mother.’

‘I know, her social worker is aware, and I’ve tried to reassure Melody that her mother can look after herself.’

‘Did you speak to my social worker?’ Melody now asked, her previous excitement replaced by concern.

‘I spoke to Jill and she’s going to talk to Neave, so don’t you worry.’

‘It’s such a shame,’ Miss May said. ‘It’s difficult for me to know what to tell her for the best.’

‘I think time will help. I’ve found before that once a child sees their parents doing all right, they let go of some of the responsibility they feel for them. Also, her social worker will talk to her mother about what she can do to reassure Melody at contact.’

‘That’s good.’ She smiled at Melody. ‘You see? There’s no need for you to keep worrying about Mummy.’

Melody gave a small nod.

I usually work closely with the teaching assistant (TA) of the child I’m fostering. Not only do TAs help the child to learn, but they often give a level of pastoral support, and help the child develop their self-confidence and self-esteem. If a child is struggling at school it can have a knock-on effect on other aspects of their life. I’d taken an immediate liking to Miss May. Short, a little chubby, with a round, open, smiling face, you felt you wanted to hug her. I guessed she was approaching retirement age, but I doubted she would retire. She clearly loved her job, just as the children clearly loved her. As we stood talking I lost count of the number of children who’d gone out of their way to call and wave to her – ‘Goodbye, Miss May!’ ‘See you tomorrow, Miss May!’ and so forth.

As Melody and I went to the car she said, ‘Don’t tell anyone, but Miss May likes sweets. She keeps a packet in her handbag. She gave me one, and the boys she helps, but no one else in the class.’

‘Lucky you,’ I said. I was pleased Melody was starting to enjoy school – some children don’t.

That evening passed as most school nights do, with dinner, homework, bath and bed. The following day was Friday and Melody had contact again. She woke up worrying about her mother. ‘I hope Mum’s not late again,’ she said anxiously. ‘I hope she remembers to come. She might not remember how to get there. I hope she has something to eat.’

‘I’ve got some dinner for her,’ I said. ‘I saved some of the cottage pie we had on Wednesday. I’ll defrost it and bring it with me.’ The look of gratitude on Melody’s face was heartbreaking. Then it was replaced with yet more anxiety. ‘It’s Saturday tomorrow, isn’t it?’

‘Yes.’

‘Mum and me go shopping on Saturday to buy food for the weekend. I won’t see her again until Monday, so she won’t have anything to eat all weekend.’

‘Melody, I am sure your mother will buy herself something to eat over the weekend. She’s an adult. Please don’t worry about her. Now come on, time to get dressed ready for school.’

I was about to leave her room when she said, ‘Cathy, you said you give us pocket money on Saturday. Can I have mine early?’

‘What for?’

‘To buy food for my mum.’ She wasn’t the first child I’d fostered who’d wanted to use their pocket money to help out their parents.

‘Love, that money is for you, but as you’re so worried I’ve got a couple of ready meals in the freezer, which your mum can have. I’ll bring them with me at the end of school and she can have them at the weekend.’

‘Thank you,’ Melody said, and threw her arms around me, which made me tear up. Clearly I wouldn’t be providing Amanda with all her meals – this was a short-term measure to stop Melody from worrying and to get them both through their first weekend apart. Amanda had her benefit money, and if she really had stopped using drugs she should have enough to buy food.

Later, before I left to collect Melody from school, I added some fruit, crisps and biscuits to the bag I was taking.