The Building of England: How the History of England Has Shaped Our Buildings

England’s cathedrals are collectively one of the supreme architectural achievements of the whole Middle Ages. This is partly a result of the inventiveness of English masons and designers, but equally of the wealth of English sees. English dioceses were larger than those on the continent and correspondingly richer. The richest, such as Winchester (£3,000 a year), Durham (£2,700), Canterbury (£2,140) or Ely (£2,000), had incomes equivalent to the most prosperous earls. Indeed, by the end of the 13th century 12 out of Europe’s 40 richest dioceses were in England. It was this wealth, carefully exploited by bishops and deans, that funded the extraordinary sumptuousness of cathedrals such as Lincoln and Salisbury. Salisbury, without its spire, cost around £28,000 over 50 years. A single bay at Lincoln (p. 96), because of the profusion of carving, probably cost twice as much as its French equivalent.32

Yet financing the construction of a cathedral was hugely expensive and it was unlikely that the normal revenues of a diocese, however rich, would suffice. At Lincoln, for instance, a fabric fund was created in around 1200, endowed by dividing the cathedral’s income in two. This was supplemented by gifts from all over the diocese responding to the disastrous collapse of 1185. To encourage more giving, continual Masses were said for those who contributed to the work. Landowners might contribute half an acre of land and symbolically place a sod from it on the altar. A tax was also levied on every household in the diocese at the Whitsun procession.33 While all these sources of income were important, financing the largest and most spectacular projects was substantially boosted by the financial muscle of a really famous saint. Although in many cathedrals Anglo-Saxon saints had been translated to Anglo-Norman buildings, their setting was now regarded as insufficiently magnificent. So through the 13th and 14th centuries the east ends of dozens of great churches were extended to provide suitably spectacular shrines for Anglo-Saxon and contemporary saints, as well as space for visiting pilgrims. This movement was given a huge boost by the new setting for the relics of St Thomas Becket at Canterbury. Thus between 1190 and 1220, for example, work started on building new eastern arms at Beverly, Ely, Hereford, Lichfield, Lincoln, Southwell, Winchester and Worcester.

As the English economy and infrastructure strengthened and towns grew, secular and ecclesiastical lords rebuilt their castles and cathedrals in new styles. Churches developed in response to changing liturgy, while the great secular residences remained much as they had done for generations, reflecting a more stable way of life for royalty and nobility. For richer ordinary people life also improved, and their houses became more sturdy, commodious and permanent.

As the second generation of Normans felt more English, so the great cathedrals, abbeys, castles and houses then under construction became increasingly distinct from their counterparts in France. Architecture had been through an intense period of experimentation from 1150 to 1170, but by about 1200 there was an increasingly uniform approach to large-scale building. Some of the excesses of late Anglo-Norman decoration were forgotten and the new Gothic style adopted simpler, but bold and deeply cut, pointed arches. Yet it was rooted in what had gone before: English cathedrals clung to the thick wall technique often with masonry 13ft thick. This not only characterised early English Gothic but influenced the proportions and scale of everything that came after. As cathedrals were rebuilt and extended they embodied the Anglo-Norman structural techniques. Thus from a European perspective early English Gothic was rich, insular and distinctive.

English architecture in the period from 1220 to 1350 displays the confidence that comes with wealth and independence.

Introduction

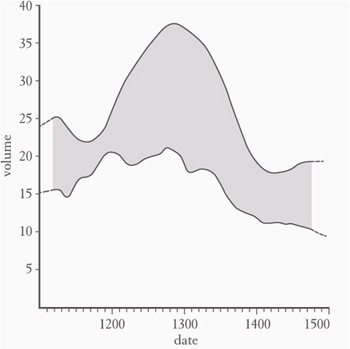

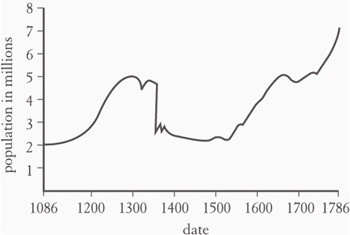

The hundred years after 1250 are among the most energetic, inventive and extravagant periods of building in English history, a time in which English architecture became as distinctive as its national character. The building boom that started in the 1220s continued strongly up to about 1300 (fig. 87). This almost precisely mirrored an extraordinary period of economic growth and national prosperity that was underpinned by rapid population growth (fig. 88).

Yet the period was not one of political stability. Politically it was characterised by a struggle between the Crown and the aristocracy. In 1215 King John had been forced to sign Magna Carta, a charter that protected barons, freemen and the Church against the arbitrary actions of the king, emphasising that royal power was held under the law. This, and the struggles to enforce it during subsequent reigns, are hugely important for England. Unlike France, where the king answered only to God, in England monarchs were not only below God but also subject to the law of the land.

John’s reign descended into chaos and civil war. He died in 1216, to be succeeded by his son Henry III, who was only nine. Most of the country was in the hands of the nobility, who were in revolt against John, and in London resided their ally, Prince Louis, heir to the French throne, whom they wished to crown king. But after the Battle of Lincoln in 1217 Henry and his party soon regained control, and Henry was to go on to reign for 46 unstable and quarrelsome years. The crisis of 1216–17, Henry’s subsequent favouritism towards foreign advisors, and the heavy-handed exercise of papal jurisdiction were important components in a strengthening sense of English identity during his reign. The process of national definition continued under Edward I, who came to the throne in 1272 at the age of 33. Edward was entirely different to his father; the first 20 years of his rule were characterised by decisiveness and determination, and saw the conquering of North Wales and almost continual war with Scotland. These years also saw persistent and heavy taxation, strengthening the role of parliament. Yet English national identity was also strengthened, partly in counterpoint to resurgent identities in Scotland and Wales.1

Fig. 87 Graph showing volume of cathedral and abbey building in England 1100–1500. The upper curve represents the average trend of 40 major building campaigns in each decade; the lower curve the average trend of campaigns started by decade at 85 buildings.

Fig. 88 The estimated population of England 1086–1786. The catastrophic effects of the Black Death in 1348 can be clearly seen.

Edward II, who came to the throne on Edward’s I death in 1307, was completely unsuited to kingship; weak, vindictive and directionless, he squandered the goodwill of the aristocracy, who had supported his father. He was deposed in 1327 and replaced by his son Edward III. On Edward III’s accession the monarchy was ineffectual and unpopular, and the king was only fourteen. Yet Edward went on to forge a reputation as one of England’s greatest warrior kings. John and Henry III had lost all the Crown’s great continental possessions except Gascony, which Henry had agreed to hold from the French king. Tension over this, and Edward’s claim to the French throne, led to the Anglo-French wars of 1337 to 1453, known as the Hundred Years’ War.

Beliefs and Ideas

The way buildings look is governed by the way people think. During the 13th century there were some significant changes in the way people thought about God and about the relationship between the Church and society. These were European streams of thought and doctrine that had varying impacts on the appearance of buildings across Europe. In terms of English architecture, however, there were three particularly important theological developments.

The first came out of the Fourth Lateran Council held at the Lateran Basilica in Rome by Pope Innocent III in 1215 that promulgated the doctrine of transubstantiation – the transformation of bread and wine into Christ’s body and blood during the Eucharist. Transubstantiation, which could only be effected by an ordained priest, further elevated priestly status above the congregation and put even greater weight on the significance of the chancel, the part of the church in which communion was celebrated. The statutes of the council made a direct contribution to a movement in England that saw, from around 1200, pressure to rebuild the chancels of churches to provide a suitable setting for the proper celebration of the Eucharist.

The second – another formal definition of an accepted belief – came out of the Council of Lyon in 1274. The council defined purgatory as the place where the soul rested between death and the Last Judgement while being refined by the prayers of the living. Prayers for the dead were now accepted as being as effective as prayers for the living – if not more so. This had a powerful influence on those rich enough to be able to guarantee prayers for themselves after they had died, and led, after 1300, to a huge upsurge in the foundation of perpetual chantries. At one end of the social and economic scale a chantry could simply be an endowment for a priest to say Mass for an individual’s soul; at the other it could be the foundation of a large college, school or hospital with a dozen or more secular priests.

At the highest levels of society those with sufficient means founded a college of priests in their own residences. Henry III did this at Westminster (St Stephen’s) and at Windsor (St George’s). Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, did the same at his mighty castle at Kenilworth. These chantries and colleges did not replace the monasteries. Monasteries continued to be very important, especially to those who could not afford customised care of their souls in private institutions. Yet, as a result, few new enclosed monastic houses were founded after about 1300.

The third development was an increasing interest in the veneration of the Virgin Mary. Before the Conquest the English had shown a strong devotion to the Virgin, but in the 13th century this developed into a national obsession. The Virgin Mary was the universal saint – she could be worshipped anywhere, free from specific geographical or personal associations and, of course, she appealed to women. Lady chapels were increasingly built to honour Mary, and became major parts of monasteries and cathedrals.

To these theological developments we need to add a fourth, of a different and more amorphous nature – chivalry. From the time of the Norman Conquest the upper classes began developing a code of behaviour – manners, if you like – that centred on physical prowess, generosity, courtesy and loyalty. How these values, which are understandable in the context of the knightly hall or the tournament, applied to the gruesome world of medieval warfare is hard to comprehend. But this exotic aristocratic culture was the way that the Church rationalised the activities of a militaristic society. In this way the brutality of the Crusades, for instance, could be fitted into a Christian world.

Entry to the chivalric world demanded excellent horsemanship, and was therefore restricted to those with the means to equip their steeds and to perfect equestrian techniques. Mounted knights practised their art in peacetime at tournaments, initially to the death but later as a form of chivalric festival. In this the cult of King Arthur and his knights was an important component, with kings and knights modelling themselves on the legendary king and his companions.2 Edward I ordered the construction of the ‘Arthurian’ round table that still hangs in Winchester Castle great hall; in 1344 his grandson, Edward III, outdid him when he constructed a building 200ft in diameter at Windsor to contain a great round table as the centrepiece of a festival at which he founded the Order of the Round Table. Arthurian legend and contemporary court life were inextricably connected.3

These romantic and militarised ideas were converted into architectural style. In this violent and warlike world castles were designed to defend their occupants from aggressors but their individual elements were often stylised. Turrets, battlements, machicolations, drawbridges and moats were as much elements of a chivalric style as functional components. Just as the 18th-century noble had a Corinthian portico, reflecting his self-image as an ancient Roman senator, so the 13th-century magnate had his machicolations, reflecting his as a heroic knight; thus from the reign of Edward I fortification was often as much a style as a form of defence.4

Fig. 89 Butley Priory, Suffolk. The early fourteenth century gatehouse is encrusted in heraldic shields representing the badges of donors and supporters.

The most obvious external sign of the chivalric mind was heraldry. Heraldic badges and devices originated with the need for identification in battle, but a more coherent system began to develop from the 1140s, and English kings adopted the red shield with three gold leopards in 1198. By this stage broad rules for using heraldic devices were being developed and, as the 13th century progressed, people further down the social scale began to use them too. In due course heraldic devices began to identity everything from vast buildings to miniature jewellery.

It was Henry III’s use of his own arms and those of his royal connections at Westminster Abbey that set the fashion for using heraldry in architectural display. Once used as a decorative element in the 1260s, heraldry remained a dominant part of English architectural decoration into the 19th century. Butley Priory, Suffolk, is not the first, but is perhaps the most spectacular use of heraldic decoration in the early 14th century. The gatehouse is the sole surviving part of a priory founded by Ranulph de Glanville, justiciar of Henry II, and was built between 1320 and 1325. On the north front is a panel with 35 shields in five rows, including the arms of the builders and a litany of arms of the great and the good, ending with a list of East Anglian gentry (fig. 89).5

Landscapes of Power

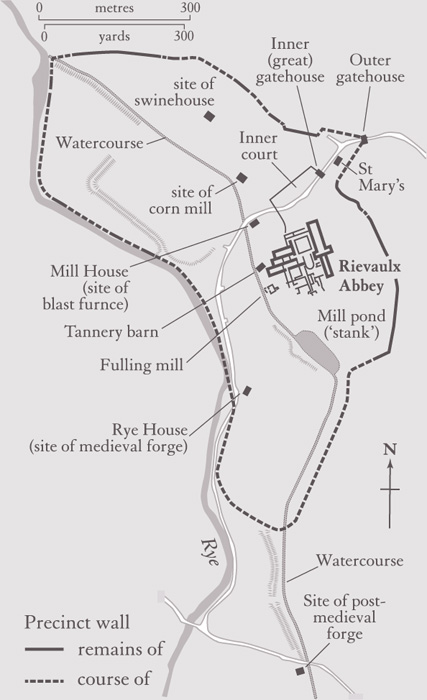

By 1220 a traveller moving across England would have seen the hand of man everywhere. The whole landscape was managed to a greater or lesser degree and few places remained untamed. The most apparent unit of economic and social management was the estate. Estates, whether owned by the monarch, the Church, the great barons or the monasteries, organised the countryside for economic advantage. But the medieval landscape was not merely a money-making machine; the buildings and structures within it had meaning to the people who owned and looked at them.

Castles had a special meaning. In theory only the king could license the construction of a defendable fortress, as in the reign of King John a system had developed whereby magnates wishing to build a fortified residence applied for a royal licence to do so. The possession of a licence, whether it resulted in a building or not, was a sign of wealth and royal favour. It was also a sign of the times. All great houses in the 13th century were, to a greater or lesser extent, defendable. They had to be. It was not only residences on the south coast or the Welsh or Scottish borders that were vulnerable to raiders. Theft, vendetta and social unrest were all potential threats to the comfort and security of the well-off. High walls and towers were thus a sign of a man who could afford them, as well as an indication that he had something worth protecting.6

For those who could not afford to build a castle or obtain a licence there was the option of digging a moat. Moats had been dug from at least the 1150s, but during the period covered by this chapter as many as 3,500 moats were dug. Some of these were dug around manor houses, some around the houses of richer peasants. Not all parts of England were suitable for moats; they tended to be concentrated in Suffolk, Essex, Hertfordshire and in the central midlands, where there was a clay subsoil. Some moated houses were in the centre of villages, others were more isolated farmsteads.

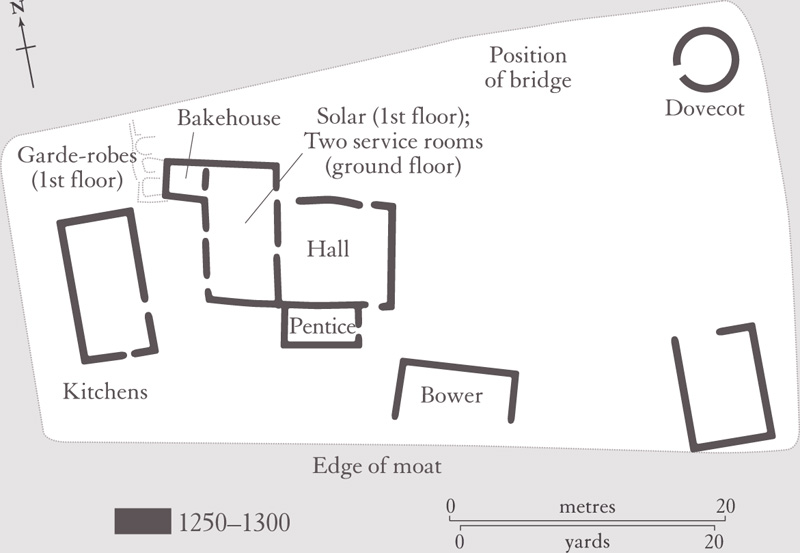

The now deserted medieval hamlet of Winteringham, Cambridgeshire, had three moated houses, one of which was excavated between 1971 and 1972. The site of the excavated house had been occupied by two earlier houses before the moat was dug in around 1250. The former houses were simpler and humbler, and the increasing wealth of the family who owned them is apparent by their desire to build a larger, more modern house and surround it with a moat. The house itself consisted of a hall and residential cross-wing, with a detached kitchen, a bower, a storeroom and a circular dovecot (fig. 90). The buildings were connected by cobbled paths. This was not the house of the lord of the manor, but of a substantial and prosperous farmer who wanted to protect his possessions from ill-doers and demonstrate his wealth by sporting a moat.7 There was, of course, a huge gap between the aspirations of the owners of Winteringham and those of the great magnates. The magnates saw themselves as soldiers and their interests were in the governance of state and Church. Culturally their priorities were, loosely speaking, chivalric, expressed in mighty residences set in extensive and beautiful hunting parks. Hunting was fundamental to the life of the aristocracy. It was the activity, above all others, that defined aristocratic rank. It took great skill, it was dangerous, and it was run through with chivalric, religious and sexual symbolism. All medieval residences of any pretensions were surrounded by hunting parks, 1,900 of which were created between 1200 and 1350. Most parks were between 100 and 200 acres in extent, the size of the park reflecting the wealth of its owner.8 The largest park in 13th-century England was the royal park of Clarendon, Wiltshire, covering 4,292 acres. It was surrounded by an impressive earthwork 10 miles long and more than 10ft high, topped with oak paling. The park was divided into three areas: pasture to the north, woodland in a band across the middle and wood pasture to the south. In addition to the palace there were eight lodges – some guarded the gates, others provided special services, such as accommodating the royal kennels. Every part of the land was productive. The woods were bounded by banks, ditches and hedges to keep the deer out and allow coppicing. Slow-growing oaks were also cultivated as a crop, and oxen and cows would graze on the wooded pasture in the south. The northern pasture supported deer and included man-made ponds for drinking and wallowing, troughs for feeding and deer houses for winter shelter. Rabbits and hares were bred here on an industrial scale and provided continuous supplies of meat. Even the wild birds were hunted with hawks.

Fig. 92 Old St Paul’s Cathedral; London: the chapter house, drawn by Wenceslaus Hollar in 1657. The chapter house and cloister were the masterpiece of the royal mason, William Ramsey. Note how the tracery of the windows continued over the walling below.

Westminster Abbey (fig. 93) was heavily influenced by French buildings and broke away from the style of recent work at Lincoln, for instance (p. 96). Its very proportions were French; at 102ft its nave is England’s highest, supported by tiers of French-looking flying buttresses. Many other elements, from its polygonal east end to its northern triple portal, are direct quotes from French buildings. Henry III, who had travelled in France in the 1240s and 50s, was doubtless looking to the French coronation church of Reims and the jewel-like royal Sainte-Chapelle as models. Yet Westminster was no straightforward copy, and the general richness of carving and surface decoration of its interior was in long-established English taste. The influence of the abbey, rather like that of early Gothic Canterbury (pp 93–4), lay not in its composition but in its details: the richness of surface decoration, the use of tracery, the carved and painted heraldic shields, the large-scale sculpted figures and smaller-scale foliage sculpture.12