The Building of England: How the History of England Has Shaped Our Buildings

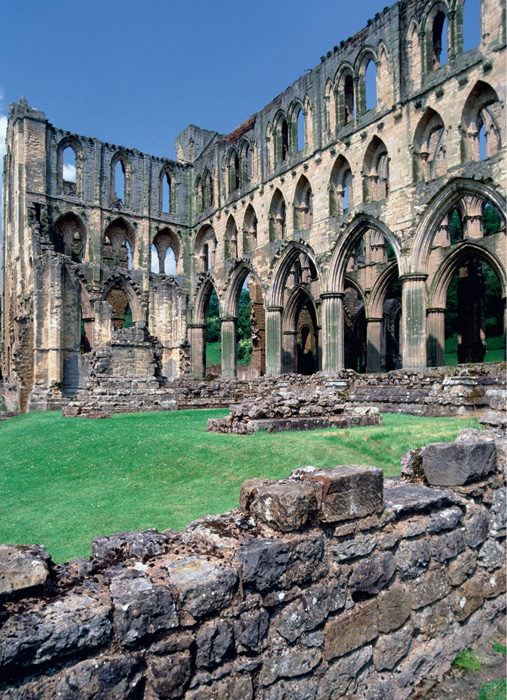

Rievaulx Abbey, Yorkshire was suppressed in 1538 and sold to the Earl of Rutland. A series of detailed accounts chronicle its partial demolition by the Earl over the following two years.

Trade was central to this. Being on an island, England had to use the seas in order to trade. It was not unique in being a seafaring nation, but, it was unique in that trade with countries other than Scotland had to be seaborne. If exports were bound for Calais, they might as well be bound for Bordeaux, too – or for that matter Bombay or Buenos Aires. In this way, once Britain had secured the freedom of the seas after its European wars it was in a position to build up a dominating global trading network.

So in terms of fundamentals, England, on a temperate and fertile island, with rich mineral resources, a powerful sense of national destiny and a strong maritime culture, was blessed with a number of advantages. These contributed in some measure to England being a populous country. Changes in its population have also had a fundamental impact on its history and architecture. In particular, relatively rapid population growth in the century before 1300, between the early 1500s and 1650, and then exponential growth after 1760 have had a wide range of important impacts, many of which have determined the narrative in this book.

A central feature of English social structure is the rights and privileges of the individual over the group or over the state. This leads to a particular view of property rights. Nowhere else in Western Europe could an owner dispose of his property with such freedom as in England; everywhere else the proportion that could be freely sold was limited by law and children had some claim over their parents’ property. In England, even with primogeniture, which became the rule from the 16th century, it was possible to sell at any time, effectively disinheriting the following generation. So English land and buildings were commodities that could be easily transferred, and all property was purchasable. Individualistic property ownership lies at the heart of the history of English building.

On four occasions in English history property transfer took place on a national scale. The first was the plunder of Anglo-Saxon estates by the Normans, in which the majority of English land changed hands; soon after there was another, less traumatic, transfer – the granting of substantial estates to the Church from the Crown and the aristocracy. By 1200 this had created the skeleton of the medieval landscape, comprising a series of great estates owned by Crown, aristocracy, bishops and abbots, a situation that remained until the 1530s, when Henry VIII triggered a third great shift. The Dissolution of the Monasteries saw a reversal of the process started during the early Middle Ages, secularising the ownership of both rural and urban estates. Despite the disruption of the Civil War and Commonwealth, which saw an assault on the lands of the Crown and bishops, the Dissolution set the scene for the whole of the period up to the First World War. After 1918 came a fourth transfer. The great estates of the aristocracy, now no longer economically beneficial for their owners, were largely, but not completely, dispersed, with ownership transferring to smaller operators and being sold for urban expansion.

In tandem with these major changes in land ownership were cyclical management decisions by landlords. From the Conquest to the First World War, landlords chose either to manage their lands themselves or to rent them out to tenants, depending on which was more profitable. So, for instance, between about 1184 and 1215 landlords took their lands in hand, but after the Black Death – between around 1380 and 1410 – lands were rented out to tenant farmers.

The ordinary English people who were involved on a micro level in these changes in land tenure were, from at least the 13th century, individualists. They were socially and geographically mobile, market-oriented and acquisitive.14 They exploited the opportunities presented by the redrawing of property ownership and in due course transformed the practice of agriculture, making England the most productive country in Europe per head.

How English Buildings Looked

Explaining how the look of English buildings changed lies at the heart of this book. But it opens up some big questions. Is changing architectural fashion down to individual whim or an expression of something deeper, a physical representation of contemporary society? Do, for instance, Georgian terraced houses, 15th-century parish churches and Victorian town halls in some way express the society in which they were produced? Is architectural innovation generated by craftsmen and designers or requested by kings, bishops, aristocrats or industrialists? Is the appearance of a building driven by its function or does a desire for it to look a certain way come first? Do engineering advances create new styles or do engineers devise ways of facilitating aesthetic effects? These questions will be addressed in the chapters that follow, but there are some general points that need to be made about how English buildings look.

Roman Catholicism was a globalising force, bringing remarkable stability across the whole of Europe from the 5th until the 16th century. There was a unity of ideas that engendered cultural conformity – and this applies to building, as to much else. English medieval building was in the mainstream of European Christian architecture, if distinctive and recognisable. The English monarchy played an important part in this, on a European scale. Starting, perhaps, with Alfred the Great’s building of Winchester Cathedral, through Edward the Confessor’s and Henry III’s Westminster Abbey, and culminating in Henry VII’s works of piety, the English monarchy was consistently among the greatest architectural patrons in medieval Christendom.

After the death of Henry VIII, who channelled much Church wealth into his own buildings, English royal building became overshadowed by the architectural efforts of courtiers and eclipsed by the buildings of foreign monarchs. It was only under George IV that the Crown started to build ambitiously again; and then it was the Crown, and not the monarch, for George’s work at Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace was paid for by parliament. Thus, after the Reformation, although architects who worked for the Crown are important in the story of English building, royal buildings themselves seldom are.

In the 16th century, better surviving documentation means that we can begin to understand what people actually thought about architecture. This has led many to see a fundamental change in people’s attitudes to building during the Tudor period. However, as this book will argue, John of Gaunt was probably no less interested, or informed, about building in the 1370s than was Henry, Prince of Wales, in the 1610s. Only we know more about Prince Henry’s interests as they have been written down. It is thus a fundamental premise of this book that people like to build and the rich, in particular, like to know about building, as it gives them pleasure and status. After all, only really rich people can build really big buildings.15 Some of the wealthy people significant in the story of English architecture are known as individuals; many are not. One of the important characteristics of English building is the consistently growing class of wealthy urban merchants, shopkeepers and professionals who demanded new types of building. Their rural counterparts were important, too, in certain periods driving innovation more urgently than the big landowners.

Burghley House, not some misunderstood attempt to imitate foreign buildings or styles but a native way of building.

Some patrons travelled and wanted to imitate what they saw abroad; some even sent their architects to learn new foreign techniques. This does not mean that English architecture is just a poor imitation of designs developed elsewhere, neither properly understood nor executed. The old view of Gothic architecture was that it was copied from France, but imperfectly, and that as classical architecture came to be admired the Elizabethans muddled it up and ‘got it wrong’. These views underestimate the insular traditions, as well as the inventiveness of English craftsmen and designers. New architectural languages were not simply copied – that was seldom, if ever, the intention. In reality, ideas, motifs and elements were absorbed and recast as new ways of building were being created.16

On a number of occasions new architectural languages were imported in a measured form that was then embellished and decorated. This reflects an underlying preference for ornamentation. The severity of Norman Winchester Cathedral (fig. 44), for instance, soon gives way to the exuberance of the nave at Durham Cathedral (fig. 51), something, perhaps, more florid and native, while the introduction of austere classical forms at Longleat House, Wiltshire (p. 212), turns into the encrustations of a house like Wollaton Hall, Nottinghamshire (fig. 195).

So there is a pendulum of taste swinging from austerity, simplicity and minimalism to ornament, colour and exuberance, and then back again. The Norman Conquest swept away the decorated buildings of the late Saxons, generating an architecture of military sobriety; but this gave way, in reaction, to the exuberant buildings of the 12th century. The way the English used Gothic from the 1170s was very austere, but this led to its elaboration and decoration from the 1250s. Simplicity of line and cleanness of form began to return in the 1340s, remaining the accepted language until the 1450s, when it became decorated and exuberant again. Towards the end of the reign of Henry VII and lasting until around 1530, simplicity and austerity returned before being overwhelmed by the theatre of Henry VIII’s court architecture. Then there was a short period of austere classical rigour from the 1550s to the 60s before a riot of Elizabethan and Jacobean decoration commenced. By the 1630s the mood swung back to minimalism, which remained to the Restoration until the richness and inventiveness of Wren, Hawksmoor and Vanbrugh become fashionable. Under the influence of Lord Burlington and his approved architects a more tempered and austere classical architecture then took over until the 1760s, when there was an explosion of decorative styles. The simplicity of the Grecian revival in the 1820s was transformed into the richness and colour of revived Renaissance styles in the 1830s. The purity of Gothic Revivalism in the 1840s then led to a riot of expressiveness of High Victorian Gothic in the 1860s, before a return to the simplification of forms of so-called ‘Queen Anne’ from the 1870s. This, in turn, gave way to a revival of interest in baroque forms, which itself stimulated a new breed of minimalist modern classicism.

Sudbury Hall, Derbyshire, built by George Vernon 1660–80. The staircase with remarkable carving and breathtaking plaster-work is at the exuberant end of English architectural taste.

Of course, moderation and excess are not opposites – they can coexist both within architecture and within the human spirit. They are different states of the same mind, not different states of mind. Yet their presence is certainly discernible to a greater or lesser extent through the building history of England. This observation is not a causal analysis nor an explanation of what happened. It is a description of a chain of events. The impulses that caused the pendulum to swing each time are complex and multi-causal – and different for each swing. The reasons that the geometric clarity of early Norman architecture was lost to Decoration are quite different from those that explain the transition from the minimalist classicism of the Restoration to the exuberance of Vanbrugh. Fashion, for that is what these changes are, can change quickly or slowly, but change it does.

‘The history of architecture is the history of the world.’17 It would be tempting to take this remark by the architect A. W. N. Pugin as a conclusion to this book. But what buildings of the past tell us is less important than the way they affect us now. We have today more of the physicality of the past around us than at any previous time. Depending on your point of view, our lives are either imprisoned by the buildings erected by our ancestors or ornamented by them. Thus, for me, it is a remark made by Sir Winston Churchill, in connection with the Houses of Parliament, that captures the significance of the story of English building: ‘We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us.’18

The fact that the constructions of our ancestors are inescapable is a profoundly levelling fact. More than anything else, the story told in this book gives the lie to the notion of progress. No mason alive today could create the high vaults over the Henry VII chapel at Westminster Abbey or the spire of Salisbury Cathedral, and no brick maker could fashion the terracotta of the Natural History Museum, London. The computer-driven precision of the contemporary glass-and-steel tower cannot be said to be an absolute advance over the brilliant eye–hand–mind coordination of the pre-modern age.

Indeed, the very notion of progress was alien to the people of England for the first 1,400 years covered by this book. Progress, as an accepted phenomenon, dates from the 18th century. For most of English history people thought in terms of trying to return to a previous, more virtuous, age. Architecture thus also gazed to the past rather than being on some forward trajectory that represented, at each step, an improvement on the previous one. The belief that progress is taking place, that it is inevitable and that it makes people happier and therefore should be pursued is not, I think, borne out by the evidence. There have been good times and bad; some of the bad times were terrible, and some of the good inspiring. Buildings, likewise, have waxed and waned. This book attempts to tell that story.

Splendid is this masonry – the fates destroyed it; the strong buildings crashed, the work of giants moulders away. The roofs have fallen, the towers are in ruins, the barred gate is broken.

The End of Rome

In 410, when the Roman army finally left Britain, neither England nor the English existed. The geographical area that is now England was part of the Roman province of Britannia and was occupied by British and Romano-British peoples. It took a long time for England to emerge from the ruins of Britannia. The first real king of England was Athelstan (924–39), who struck his coins with Rex totius Britanniae (King of all Britain). Athelstan inherited a rich, successful, populous kingdom ornamented with churches, cathedrals, monasteries and palaces. So, technically, the history of England’s architecture begins in around 900, but to understand how England looked then, and why, we need to start in 410.

This is easier said than done. The evidence is wafer thin – few buildings, a few more manuscripts and a volume of archaeological excavation carried out, not systematically, but where opportunities arose. The result is that the period 410 to 1000 is an incredibly controversial one, with heated debate among archaeologists and historians not only about why things happened, but what happened, and when.

One of the difficulties is that England was at least two and sometimes three different places before 1000. Indeed, Roman Britain itself had culturally been two places: the south and east, which were more Romanised, and the north-west and west, which were less heavily Romanised. Similar distinctions remained in Saxon England, with the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings making a bigger impact in the south and east than, for example, in Cornwall. The southern parts, particularly Kent, had closer ties with the continent, while Northumbria was more influenced by Ireland. As a result, it is very hard to generalise about England as a whole, but it will be necessary to make some generalisations if any sense is to be made of this complex period.

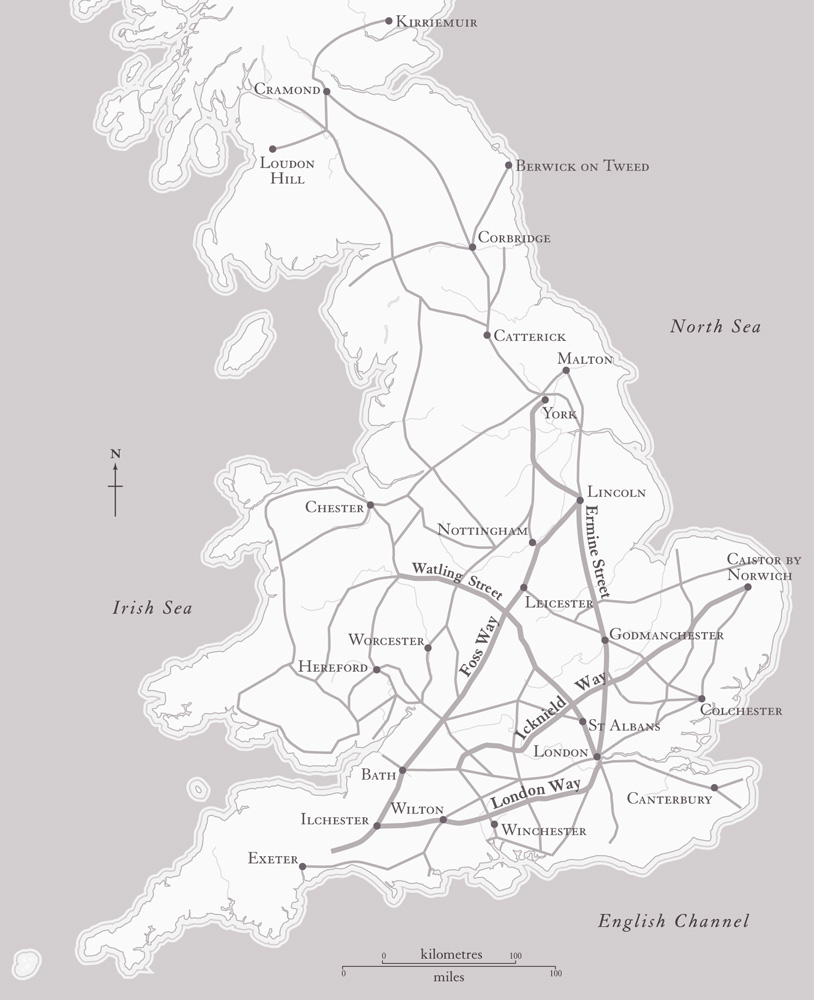

The Romans were in Britain for an extremely long time – if they had left in the year 2000 they would have arrived in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. During the centuries of their occupation they built a very great deal: there were over 60 towns, places of administration, justice, manufacture, trade and latterly church administration. Some were large, with populations of 15,000 or more, at least as large as medieval towns such as Norwich. In some areas the countryside was littered with villas and the coast with a messy series of forts. Hadrian’s Wall, with its forts and towns, protected the Empire’s northern border. Internal fortifications, too, were mighty. Many towns were walled, and the largest of these, like York, was built almost impregnably in stone (fig. 1).

Fig. 1 The Multangular Tower, York. The lower part of this fourteen-sided tower dates from the late 3rd or early 4th century and formed part of the Roman fortress of York. The upper stages were rebuilt and reused in the 13th century. Throughout the early Middle Ages large Roman structures such as this dominated many English towns.

In 410, in the face of complex problems across the empire and a decline in the importance of Britannia, the Emperor Honorius ordered the remaining units of the Roman army to leave Britain and told the Romano-British to fend for themselves. With the exit of the army came the collapse of Roman state control and its economy. The legions had been responsible for maintaining centralised government with coinage and taxation, laws and the physical infrastructure of roads and fortifications. Their removal exposed what was to become England to the destructive forces of the barbarian world.1

The first wave of settlers that came to East Anglia in the first half of the 5th century was from northern Germany. They were farmers attracted by the agricultural potential of England who had little direct experience of the Roman way of life – and even less interest in it. These peoples kept contact with their homelands, moving backwards and forwards, bringing and transferring fashions in everything from weapons to jewellery and, of course, buildings. The newcomers were not especially numerous but were highly successful at establishing themselves, by force, as the landlords of the native British population. So much so that by 600, although the genetic make-up of what is now England was still heavily British, people spoke Anglo-Saxon, worshipped Germanic gods and shared Germanic fashions. A hundred years later there was a sense of emerging Englishness, but not politically, for the land that became England was still divided into a number of small kingdoms, each with its own kings, customs and ambitions (fig. 2).

Many towns had already been in decline before the legions left, but after their departure the collapse was sudden and fundamental. We know that people continued to live in some of them after the Roman administration ended – in Colchester, Cirencester, Wroxeter, Carlisle, St Albans. But this was not a continuation of urban life, with civic, social and economic structures. It was life in towns, not town life. This is fundamentally different to what happened in Gaul; there, Roman cities formed the building blocks of Frankish rule. From these places taxes were levied, in them administration was centred, and to them secular and ecclesiastical rulers were attracted. So why were the British Roman towns abandoned?2

This fascination with Rome is a thread that runs through this book. There is a sense in which the history of English architecture until the late 18th century can be explained as a quest to re-create Roman buildings. King Alfred the Great at Winchester (p. 46), William the Conqueror at the White Tower (p. 69), Edward Seymour at Somerset House (p. 280) and Lord Burlington at Chiswick (p. 318) were all trying to achieve the same thing. And it was not just the 18th-century Grand Tourists who went to Rome in person; in Anglo-Saxon England kings, bishops, parish clergy and ordinary people all made the long and dangerous pilgrimage to Rome. In the Leonine City on the edge of Rome was the Schola Saxonum, a lodging house for English pilgrims supported by a tax raised by English kings. England was no provincial outpost; those who had the wealth to commission buildings were not ignorant of the great buildings of the ancients in Rome.6