The Building of England: How the History of England Has Shaped Our Buildings

The Mercian Kingdom

In the 8th century the kingdom of Mercia was dominated by two very powerful and successful kings who controlled most of England south of the River Humber. Ethelbald (716–57) and Offa (757–96) were the first kings able to organise huge labour forces to solve surveying, engineering and construction problems on a national scale. Ethelbald was probably responsible for starting a concerted programme of bridge and road building to improve communications. No Anglo-Saxon bridge now survives – most were probably of timber – but before 1000 a network of bridges carried roads on both local and national routes.3

Offa is of particular importance as an international figure who corresponded with Charlemagne and was a friend of Pope Hadrian. He is also significant as the builder of Britain’s largest monument: the 150-mile-long Offa’s Dyke (fig. 13). The dyke was probably constructed to keep Welsh raiders out of Mercia and had 6ft-deep ditches with a 25ft bank behind; the rampart was topped by timber palisading and, in places, stone walls. Offa was able to mobilise labour for this and for the fortification of towns, marking a major change in the way England’s landscape was moulded by the power of the state. Offa’s achievements in church building were no less impressive, if only fragments of his churches now survive. Much to the chagrin of Canterbury, Offa used his influence with the Pope to found a new archiepiscopal see at Lichfield. Nothing of Offa’s cathedral remains except for a fragment of a contemporary shrine chest associated with the cult of St Chad (fig. 14). This carving, one of the most beautiful and moving to survive from Saxon England, reveals Mercian carvers following Carolingian fashions, reviving the sculptural style of the early Christian Church.4

Fig. 14 The corner of a tomb chest of c.800, probably from the shrine of St Chad, who died in 672. This fragment, found in 2003, shows that Mercian sculptors and architects, like their continental counterparts, were reviving late Roman styles.

Fig. 15 St Wystan’s, Repton, Derbyshire. The mausoleum of King Wiglaf of c.830. This compact but richly articulated space contained recesses to take the tombs of the Mercian royal family.

An even more potent expression of Mercian interest in early Roman Christianity is their royal mausoleum at Repton, Derbyshire. The crypt here was first built as a freestanding burial chamber for the kings of Mercia. King Wiglaf, before his death in 839, transformed the chamber from a plain rectangular cellar into a spectacular mausoleum by incorporating it into the chancel of the church and building an internal vault supported by four twisted stone columns based on the most prestigious late Roman Christian monument in Rome: the tomb of St Peter. This daring allusion gave voice to the power of Mercian kings in the language of Carolingian Europe (fig. 15).

More substantial evidence of the Mercian revival of Rome is the church of All Saints’, Brixworth, England’s most exciting and impressive standing Anglo-Saxon building (fig. 16). The church is big, about 160ft in length, but is now shorn of its ‘porticuses’, five on each side, which originally flanked the open hall of the nave, rather like aisles in later churches, but subdivided into individual chambers. East of the nave was a separate space, a choir, enclosed by an apsidal sanctuary beneath which was a crypt encircled by an enclosed passageway.5 The nave arcades are truly massive, their voussoirs made of reused Roman brick; whoever commissioned and designed this church was deliberately and successfully recreating a sense of Roman monumentality, and might have known contemporary Carolingian buildings.6

How many such churches existed in Mercia or elsewhere before the Vikings is quite unclear, but it is unlikely that Brixworth, and the major minster excavated at Cirencester, Gloucestershire, were the only two. These structures put architecture in England in the 8th and 9th centuries in the same bracket as some of the most avant-garde structures in Europe.

Fig. 16 All Saints’, Brixworth, Northamptonshire. This powerful church (the largest surviving Anglo-Saxon church in England) would have been even more massive before the demolition of its porticuses. The blocked-up ground floor arches along the nave would have originally led into these, just as at St Peter’s, Wearmouth (as shown in fig. 8). The tower with its semi-circular staircase projection is probably 10th century.

The Anglo-Saxon Church

The importance of churches to Anglo-Saxon society cannot be overestimated. Whilst kings were mobile, their buildings only occasionally utilised, and their economic effects dispersed, churches were rooted to a single location and thus became centres of economic activity and often, in due course, the kernel of towns. Minster churches also needed land to support them, and Church land, unlike the land owned by aristocrats, was not transferable between generations but held in perpetuity. The amassing of land by the Church contributed to a shift in focus from movable wealth, a feature of Germanic societies, to the idea of permanent land holding, as in Roman times. Land transactions were thus increasingly recorded and legalised, and the landscape divided and packaged.

In addition to landed endowments, often provided by royal or aristocratic patrons, relics, pilgrimages and miracles were the trinity that underpinned the building economy and design of the medieval church. For Saxons, relics had supernatural power. They were placed inside altars, carried into battle, used for solemnising oaths; without them no church was able to function. The more famous the relic, the greater the chance of attracting pilgrims who would make gifts of money at the shrines they visited. But pilgrimage was not only a pious act; it was a visual education for the clergy, builders and the laity. It was the cause of mobility and design exchange, of competition and of rising architectural expectation.7 Even modest numbers of pilgrims set architectural problems for church designers. People needed to be able to come close to relics in an orderly and controlled way that enabled suitable donations to be made, and satisfaction with the experience to spread by word of mouth.

One of the most conspicuous innovations connected with pilgrimage was the crypt, a small underground chamber, normally under the high altar, designed to contain relics. It was the crypt at St Peter’s, Rome, that established this feature as an aspiration for any late Saxon church. Brixworth (fig. 16) originally contained a ring crypt that allowed pilgrims to move round the apse, venerating relics, and the mausoleum at Repton was appropriated as a shrine to St Wystan, a royal prince murdered in 849. For this, a new access was cut, providing a proper circulation for pilgrims (fig. 15). Visitors to Repton and the surviving Anglo-Saxon crypts at St Andrew’s, Hexham, and at Ripon Cathedral can still explore the mysterious and gloomy subterranean circulation designed to lubricate the flow of pilgrims.

If the need to provide access to relics above and below ground was a fundamental factor in the design of the Anglo-Saxon church, so was the Saxon view of the Eucharist. Whilst Christ was obviously the focus for worship, it was the consecrated bread – the host – itself, as a sort of super-relic, that was venerated. Inside chapels the host could be placed on an altar alongside other relics, forming an easily multiplied supernatural focus. Because the moment of consecration was less important than the veneration of the host, Saxon churches were not as focused as later medieval churches on a single altar at the east end. Rather they comprised an assemblage of compartments on several floors, each with its own ritual focus. The most common and flexible of these subdivisions was the porticus, which served as side chapel, tomb chamber, sacristy or viewing chamber. The most important and impressive was the westwork,8 an enlargement of the west end of a church to provide a location for relics or shrines, a western choir, or occasionally a high-status viewing place (p. 46). These secondary spaces became progressively more important with a rise in the doctrine of purgatory and the appropriation of individual chapels by the rich for prayers to be said on their behalf. They also appealed to aristocratic aesthetic sense, which tended to the more ornamental, decorative and intricate than the big and bold.9

Before the 670s Christians did not expect to be buried in or near churches but were buried, like pagans, in cemeteries. By the late 7th century, however, the Church had wrested control of burial rites from friends and neighbours, and started to bury the dead close to Church buildings. Burial within churches themselves remained controversial and was made available only to individuals of the highest status. By 850, however, Christian cemeteries were serving large numbers of ordinary people, taking in land that was increasingly walled or fenced and populated by grave markers.

Monasteries

The Viking raids were devastating for early English monasticism. Whilst some monasteries survived, and some semblance of communal life might have remained, England’s former glittering monastic tradition, with its learning, music and patronage of art, was effectively wiped out by the Vikings. The decisive moment in the re-foundation of English monasticism came in 939 when King Edmund (939–946) set up Dunstan as Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey. This was a decisive move because Dunstan’s monastery, in line with those in the Carolingian empire, was founded according to the rule of St Benedict and Glastonbury went on to influence the foundation of thirty more Benedictine monasteries in southern England in as many years. At first each of these houses interpreted the rule as it wished, and it was not until King Edgar’s monastic reform that a consistent version of the rule of St Benedict was imposed on all the largest and richest minsters by the Regularis Concordia of 973.

Fig. 17 St Mary’s, Deerhurst, Gloucestershire; view of the interior looking west. On the ground floor is the Saxon door leading into the tower. Originally above this was a timber gallery – the blocked door that gave access to it can be seen. The corbels in the corners would have supported the gallery. The two pointed windows above looked into the church from a large room in the tower on the other side.

The Concordia put English monasticism on a level with contemporary continental practice. There were, however, some important specifically English provisions. As a concession to English weather, during the winter monks were allowed to have a fire in a warming room and permitted to work inside rather than in the cloister. More overtly political and nationalistic was the fact that the king and queen were to be recognised as patrons and guardians of monasteries, and that they should be prayed for at each of the daily offices bar one.10

In the hundred years after the Regularis Concordia kings and aristocrats lavished gifts of land on the monasteries, so much so that by 1066 nearly a sixth of the income of England was held by monasteries in lands and rents. This not only made them a hugely significant economic force but created vast wealth for architectural display. So little remains of any of the thirty or so monasteries reformed in the 10th century that it is hard to generalise about them, but it does seem likely that most of the components of later medieval monasteries were already in place, such as the cloister, refectory, dormitory and warming house. The abbey churches, however, were very different from those that remain today.

Fig. 18 St Andrew’s, Nether Wallop, Hampshire. The paintings over the chancel arch are the best preserved Saxon murals in England. They show angels censing a lost figure of Christ. Such paintings would have been commissioned by wealthy patrons, in this case possibly the powerful Godwin family who held land in the area.

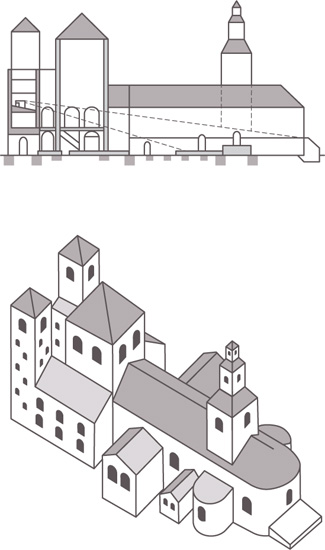

Fig. 19 Winchester Cathedral, the layout of the Old Minster as recovered by excavation lies next to the later cathedral. Right, isometric diagram and cross section of the Old Minster at Winchester c.993–4, as reconstructed by the Winchester research unit based on excavations. The massive western towers – the westwork – probably contained the royal chapel or pew from which a view of the high altar was possible.

A single example of a Mercian minster church, begun in around 804 and re-ordered in around 970, survives at St Mary’s, Deerhurst, Gloucestershire (fig. 17). This precious survival, before it was converted to a parish church, was a complex, multi-focused monastic church on a series of levels. At the west end was a four-storied porch containing three upper rooms, the room on the first floor housing a chapel with a deep gallery overlooking the nave. The taller and more impressive room above had two elegant windows giving clear views of the church interior; there was another balcony here, but this one was on the exterior of the west porch, allowing, perhaps, the display of relics to people outside the church. The porticuses to the north and south of the choir were two-storied, their first-floor rooms containing doors leading to an eastern gallery over the choir; the chancel was a polygonal apse also with a room above, with a balcony looking into the church.

St Mary’s not only provides the best place to understand the complexity and ingenuity of Anglo-Saxon liturgical space, it also allows us to come closer to an appreciation of the way church interiors originally appeared. The interior of a church like St Mary’s was richly painted, not only with figurative murals, but with carving and mouldings painted and decorated with organic patterns.

Whilst the surviving figure-work at Deerhurst is very faded, at St Andrew’s, Nether Wallop, Hampshire, the lower part of an impressive mural of Christ in majesty survives from about 1000 (fig. 18). This decoration is painted in styles familiar to us from Anglo-Saxon manuscript illumination and decorative art. Whilst painting occasionally survives, very few Anglo-Saxon textiles do, but it is clear that prestigious monasteries and cathedrals, as well as richly endowed minsters and smaller foundations, were hung with textiles, often on the walls. These would have been a backdrop for rich metalwork in gold, silver and wrought iron. Aethelwig, Abbot of Evesham, adorned his church with ‘a great many embellishments – chasubles, copes, precious textiles, a large cross and an altar most beautifully worked in gold and silver’. The overall effect of a great Saxon church interior would have been overwhelming. Anglo-Saxon taste was for richness, intricacy, detail and ornament, all of which added to the complexity and disorienting effect of liturgical space: balconies, side chapels, crypts, winding staircases, all painted and hung with textiles, dimly lit by lamps or windows filled with coloured glass, created a sense of mystery that it is impossible to gain from the whitewashed shells that remain.11

The residential parts of minsters have all vanished, but, from what we know, they were, like royal buildings, centred on great halls. It is likely that the stone hall, 120ft long, excavated in Northampton and dating from around 860, was part of a minster complex. This is where an abbot would have administered his estates, dispensed justice and entertained.12

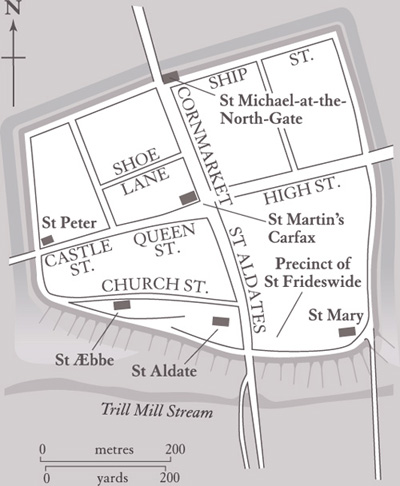

Bishops and Kings

Early English dioceses were based on Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and, as power and territory ebbed and flowed between them, they were reorganised many times. The Viking incursions provided an opportunity to redraw the diocesan map, and after the 10th century dioceses more or less coincided with the new administrative shires of England (fig. 12). But there was no particular conformity of diocesan organisation; cathedrals were organised in different ways and many, uniquely for England, were also monasteries where the bishop lived his life in a monastic order.

Thanks to painstaking excavation, more is known about Winchester than any other Saxon cathedral. It was arguably the finest building standing in England at the Conquest. By 1066, however, Winchester had already had a cathedral for 418 years; this was the Old Minster, with a cruciform (cross-shaped) plan and a square end. Over the ensuing centuries the cathedral was enlarged and adapted so that by 1000, as well as the nave and high altar, it comprised four towers, three crypts, three apses, at least 24 smaller chapels and a baptistery (fig. 19). Despite strong English characteristics, the Old Minster was, by the time of the Normans, a church with a recognisably Carolingian plan. Most prominent was the westwork – the enormous, tower-like structure erected at the west end of the cathedral in the 970s. Westworks developed in Carolingian churches in the 9th century and went on to form a component of many great churches in France and Germany built from the 10th to the 12th centuries. At Winchester the huge west towers performed a dual purpose, providing a focus for liturgy and an occasional grandstand for the kings of Wessex to view events in the main church below. Winchester, built next to the royal palace of Wessex and functioning as a dynastic church, might have been exceptional. More typical, perhaps, was the westwork of which fragments, surprisingly, survive at Sherborne Abbey in Dorset. The see of Sherborne was founded in 705 but came to prominence in the 9th century, when two of Alfred the Great’s brothers were buried there. Bishop Aelfwold rebuilt and extended the cathedral between 1045 and 1058 in a form heavily influenced by developments in the Carolingian empire (fig. 20). The upper chamber in the west tower contained an apse in which the bishop’s throne was positioned, opposite him; at the east end was a three-light window looking down into the main body of the church and before this stood the altar. This arrangement allowed Mass to be celebrated in public view in the upper chamber and distinguished members of the congregation to watch from chambers on either side.13