The Building of England: How the History of England Has Shaped Our Buildings

How the Saxons Built

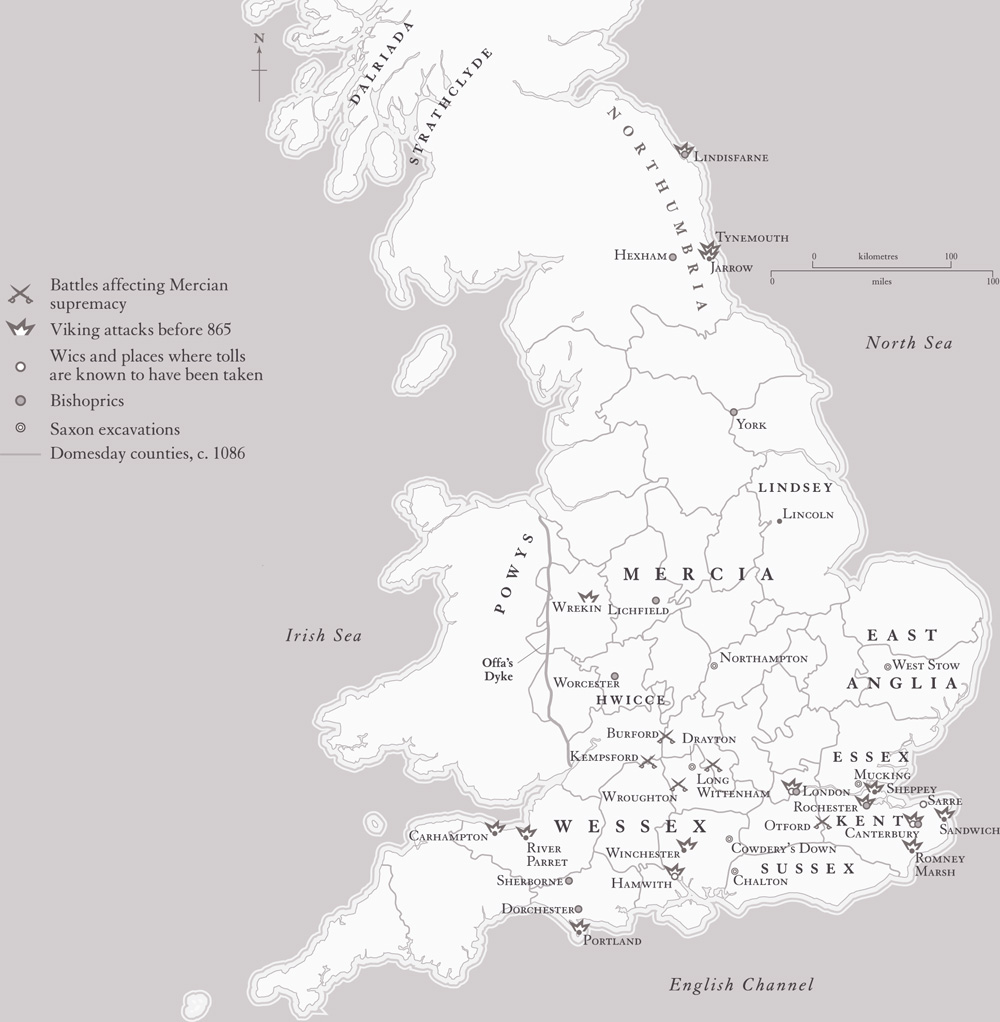

The early Anglo-Saxon world, unlike ours, was not primarily a built one. Special places were normally natural ones: rivers, hills, woods. Indeed, their language had words for circles and curves, but expressing straight lines and right angles was difficult. The natural world therefore played a large role in building. Most churches, for instance, were not aligned by compass point to the east, but were laid out by sighting the sun at sunrise and sunset either on saints’ feast days, Easter, or on the spring or autumn equinoxes.7

Almost all secular buildings were built of timber; indeed, the Anglo-Saxon verb ‘to build’ is timbrian, and buildings were getimbro. Timber was not seen as a lower-status material than stone, nor was the skill to use it effectively lesser than that of the mason. Indeed, even in the early Saxon period, the achievements of leading English carpenters were considerable. That English building between the Romans and the Vikings was almost entirely of timber demonstrates that efficient woodland management must have continued after 410, albeit at a local level. This involved cyclically harvesting the underwood (coppicing) but allowing the oaks to grow in longer rotations (between twenty and seventy years). Coppicing provided fuel as well as all the non-structural building timber, including poles for scaffolding. Oaks were selected by carpenters, felled, their branches and bark removed, and then squared up and used for the structure of buildings. Oak was worked green (without being seasoned), the structure tightening up as the timber dried out. The most important woodworking tool was the axe used for cutting and smoothing, but hammers, adzes, boring-bits, chisels, gouges, planes and saws have been excavated from Anglo-Saxon sites. Nails were not used and fastening was by simple joints with timber pegs. The highest-status buildings might also include iron straps, hinges and catches, as ironworking and smithing continued after the Romans left.

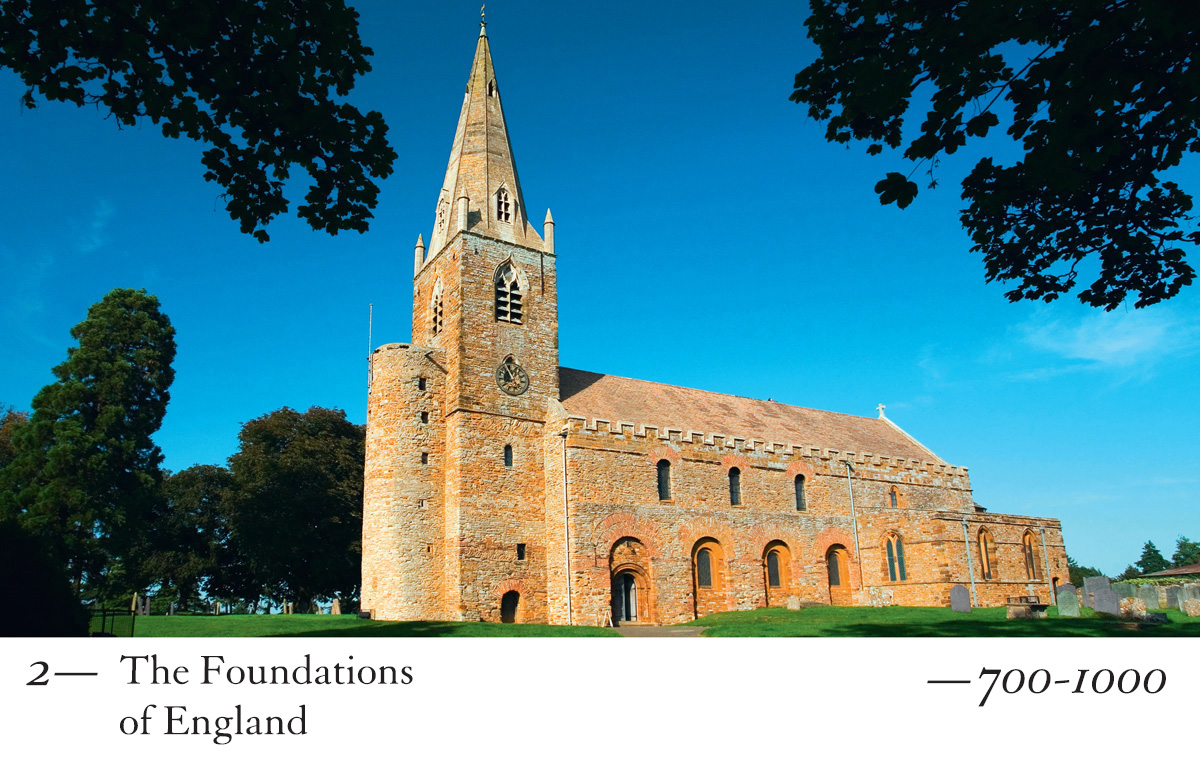

Fig. 3 St Peter’s, Wearmouth, County Durham. The lowest stage of the tower was built in around 680 and was originally a single-storeyed porch; it was heightened c.700 and then again in the later Middle Ages. The remarkable porch, which never had doors, is flanked by cylindrical stone drums probably turned on a lathe like timber balusters. The Saxon nave lies behind the tower; the aisle to the left is 13th century.

Coppicing produced the wattles necessary for certain types of wall construction. Wattling involves a row of upright stakes, the spaces between which are filled by interweaving flexible branches, often rods of hazel, which are then covered with daub, either mud, clay or, in more sophisticated buildings, lime plaster. Roofs were not covered with slate, tile or stone, as was often the case in Roman times, but only with thatch or shingles. The best thatch was made of reed, but most often it was straw or even hay attached with string or hazel rods. Shingles were small, geometric slithers of oak pegged or nailed to the roof structure, more durable than thatch and less prone to catch fire.8

Stone building implied infrastructure and organisation. Quarrying, transport and construction require the mobilisation of significant expertise and labour. All this disappeared after 410, and by 600 there can have been few masons left in England. Masonry was re-introduced by Christian missionaries and relied entirely on robbing Roman buildings for a supply of cut stone. It was not only the expertise that was lacking to restart quarrying, but the motivation; the ruins of Rome were a plentiful quarry and most Saxon stone buildings were built close to or among the ruins of Roman sites.9 Where stone was used in a decorative fashion by the Saxons it was often carved as wood. The right-hand jamb of the archway at the base of the tower at St Peter’s, Wearmouth, County Durham, of c.680 is a perfect example of the woodcarvers’ art translated into stone (fig. 3).

Fundamental to the reintroduction of masonry building was the rediscovery of mortar; without this, stones could only be laid dry on top of each other at a very low height. Excavations at Wearmouth have revealed the earliest example of a post-Roman mortar mixer, a pit for mixing lime mortar with large, rotating paddles. The expertise for constructing this came from Gaul and required limestone to be burnt in a kiln before being mixed with water to form lime mortar.10

Where People Lived

In the years after the collapse of Roman rule power did not reside in fixed places – capitals, if you like; it resided with individuals moving from place to place. Leaders principally expressed their status through portable wealth, through personal adornment, through individual prowess and the ability to provide their entourage with great feasts. Places were occupied for short periods so that rulers could receive food-rents from surrounding farmers, feast with their households and move on. Yet the rulers who emerged in England wanted, as much as their Roman predecessors, to create monumental expressions of their power. In the Saxon poem Beowulf the heroic struggle between Beowulf and the monster Grendel is set in a spectacular timber banqueting hall, with doors bound with ironwork, and a carved and gilded roof strengthened by iron braces. Quite a number of these halls have now been identified, either by aerial archaeology or by excavation.11

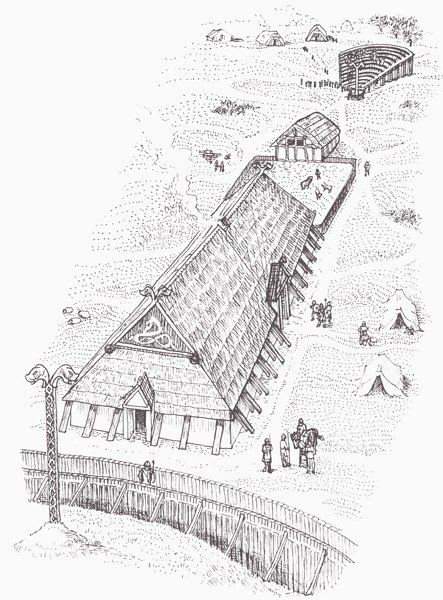

Fig. 4 A reconstruction of the royal hall at Yeavering, Northumberland, based on excavations in the 1950s and 60s. Started by King Edwin in the 620s, this great hall and accompanying structures, including a grandstand looking like a Roman theatre, would have been used by the king when he visited the region to feast on food rents owed to him by his subjects.

The only one that can certainly be identified as being royal was the complex of the Northumbrian King Edwin at Yeavering, Northumberland, started in the 620s.12 There the excavators found a number of halls built in succession after a series of fires. The important point is the size and sophistication of these structures. The hall christened A2, for instance, was 82ft long and 36ft wide, had an entrance in the centre of each long wall, and two internal cross-walls making separate rooms at either end. The main hall was aisled and so was interrupted by supporting posts. The walls were made of planks sunk into a trench, then plastered inside and out. It is very likely that these were painted, and that beams and posts were elaborately carved (fig. 4). This was a building that required craftsmanship, engineering and organised labour, and it is likely that it was built in a tradition that was uninterrupted since the Romans. Roman villas had great halls or barns that are archaeologically almost indistinguishable from Saxon halls such as the one at Yeavering. In fact it is possible that some large Roman timber halls might have remained in use well into the period covered by this chapter. However, although the techniques necessary for their construction were probably essentially Romano-British, their decoration might have owed more to the traditions of their Anglo-Saxon owners.13

It was not only kings who built great halls. With royal grants of land, leading nobles also built places as estate centres and for feasting. It is likely that the remains found at Cowdery’s Down, Hampshire, are just such an aristocratic settlement dating from the 6th century. Fine timber halls, palisaded enclosures and more humble timber houses were found in a tight-knit plan, demonstrating that the building technology available to kings was also used by the richest landlords. Here, again, the halls and houses owed much to Romano-British building traditions, suggesting continuity of structural techniques.

The places that these individuals chose to make their base, whether as living kings or as corpses, were often ones that had been significant in the Iron Age or earlier. This is the start of a phenomenon that is very strong in England’s architectural history, the desire of the powerful to emphasise their legitimacy through references to the past. The locations of both the royal palace at Yeavering and the royal mausoleum at Sutton Hoo were influenced by pre-existing prehistoric settlements and barrows.14

This continuity of place seems to have affected lower-status settlements, too. Through the extraordinary upheavals and changes of the period Britain’s population had remained fairly static. From the late Roman period to about 700 most people continued to farm the same landscapes that they had farmed from the late Iron Age, in a similar manner, and living in similar buildings.

Fig. 5 A reconstructed 6th-century house at West Stow, Suffolk, based on archaeological excavation. The village contained five such halls strung out along the ridge of the hill, forming the spine of the settlement. A fire would be lit in a hearth in the middle of the single internal room.

Early Anglo-Saxon settlements were not villages in the sense that we would understand today. They were places occupied over a long period by perhaps ten families at most; built structures, all of which were of timber, would be replaced many times. These settlements were very loose, unfenced and unstructured, without streets or apparent geometry. At West Stow, in Suffolk, just such a settlement of the 5th and 6th centuries was excavated in the 1960s. Its inhabitants lived and worked in houses of a type prosaically described by archaeologists as Sunken-Featured Buildings. These were made by digging a rectangular pit over which a timber floor was suspended. Walls were made of planks sunk into the ground, and uprights at each end supported a ridge pole (or poles) that supported a thatch roof. These buildings were ubiquitous in English settlements from the 5th to the 8th centuries and were an Anglo-Saxon import, direct copies of a type of structure found all over northern Europe. In addition to the Sunken-Featured Buildings at West Stow there were larger, sturdier halls, probably for communal use (fig. 5). These bore less resemblance to their continental equivalents and are much more similar to Romano-British houses dating back to the later 1st or 2nd centuries.15

The Church before the Vikings

Although, when Pope Gregory sent St Augustine and his missionaries to England in 596, he was sending them to a place he regarded as at ‘the end of the world’, it was to one that had a Roman heritage. He instructed that bishops be seated in the Roman towns of Canterbury and London; perhaps he thought England was still the urbanised, centralised Roman society that it had once been. It was not. But despite this, Augustine did in fact found a see based on Canterbury, where he built England’s first cathedral, possibly on the site of an earlier Roman church. Outside the Roman town he also built a monastery, later to be given his name.

Further cathedrals were to be founded at Rochester and London and, in the 620s, at York. A cathedral is a church that contains the cathedra, or throne, of a bishop; this is, in fact, the only difference between a cathedral and any other sort of large church. In their dioceses bishops were responsible for ordaining priests, consecrating new churches, dealing with clergy discipline, and administering land and finances. As such they were crucial in the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons.

After several faltering starts England had become Christian again by the 680s, and in 664 the Synod of Whitby had settled that the English Church should be modelled on that of Rome rather than the Irish Church. Within a century England was populated by several hundred minsters, that is to say churches with a residential religious establishment, and was divided into seventeen dioceses. Not enough survives of any early Saxon cathedral to say much about it, but several minsters do, and from these we can paint a picture of the first Saxon churches.

Remarkably St Martin’s, the very first church of St Augustine and his fellows, survives in Canterbury, incorporating the brick remains of a Roman tomb (fig. 6). This ancient church, possibly first used as a mortuary chapel, though mauled and altered by time, is a powerful and evocative place to visit and is typical of the first places of Christian worship in Saxon England, built in close proximity to prominent Roman sites and constructed out of re-used Roman materials.16

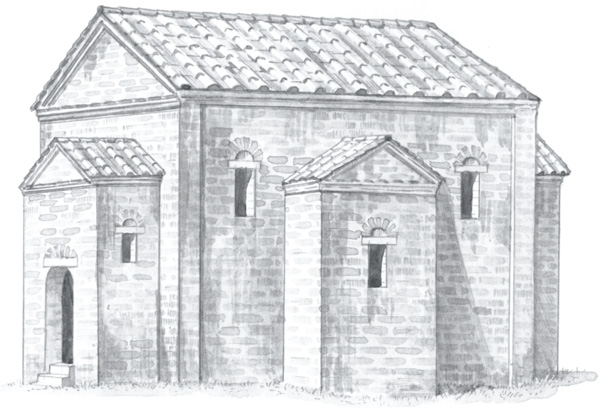

Fig. 6 St Martin’s, Canterbury, Kent. A reconstruction of the church of Bertha, Christian queen of King Ethelbert; St Augustine first worshipped here in the 590s. The walls of the present nave are partly Roman and may have originally been part of a tomb chamber. Though significantly altered, St Martin’s remains the oldest standing church in England.

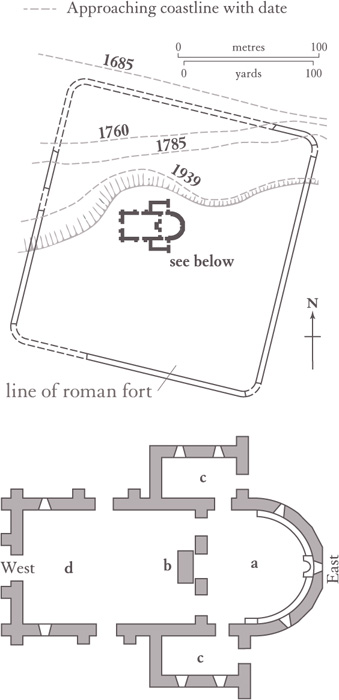

Fig. 7 St Mary’s, Reculver, Kent, of 669 from an excavation in 1927. The church was built in the middle of the Roman fort out of reclaimed materials. a) apse with bench and throne; b) altar framed by central arch; c) porticus; d) nave.

St Mary’s, Reculver, Kent, now precariously perched on the edge of a cliff, is a more complete example (fig. 7). In 669 King Egbert of Kent founded this minster in the centre of the old Roman fort. Most of the fort has now fallen into the sea and the church is abandoned, but it has been excavated. In plan it has a stubby, rectangular nave with an apsidal (semicircular) chancel lying behind a screen of two columns. On the north and south there are subsidiary rooms, known as porticuses. The apse, which contained a semicircular bench with a separate seat or throne in the middle, was an area set aside for the clergy, who celebrated communion facing their congregation in the nave. It is doubtful that St Mary’s could have been erected by Saxon craftsmen, whose architectural tradition, as we have seen, was entirely in timber. The strong likelihood is that St Augustine brought masons with him from Italy who designed and constructed these early Christian churches; a likelihood that is strengthened by their stylistic similarity to the churches of Ravenna in northern Italy and the Alps.17

Roman missionaries from Kent took the gospel to Northumbria, where, after the Synod of Whitby, more minsters were founded. The twin foundation of Wearmouth (today Monkwearmouth, 674) and Jarrow (681) is by far the most important of these. Like St Mary’s, Reculver, these churches were not designed by native hands. Their founder, Benedict Biscop, who had travelled Europe for sixteen years absorbing the latest ideas for the organisation and construction of monasteries, enlisted Frankish stonemasons and glaziers to construct his monastery in Roman fashion. They took their carts and their measuring rods to the Roman forts on Hadrian’s Wall and returned with both building materials and construction techniques for the new minsters. Both were thus, in terms of fabric and technique, built in the Roman manner, and their dedications – to St Peter and St Paul, the patron saints of the Roman Church – confirmed that life there was to be based on Rome, too.

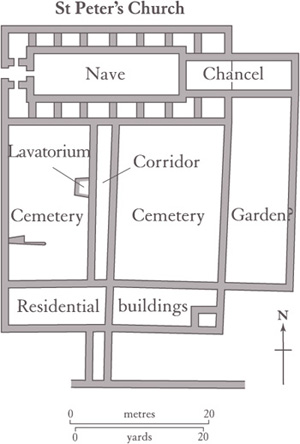

Fig. 8 The Monastery of St Peter’s, Wearmouth. Plan based on excavations showing the layout of the latest phase of the Saxon monastery. The church, with its skirting of porticuses, was linked by a corridor crossing the cemetery to the living quarters.

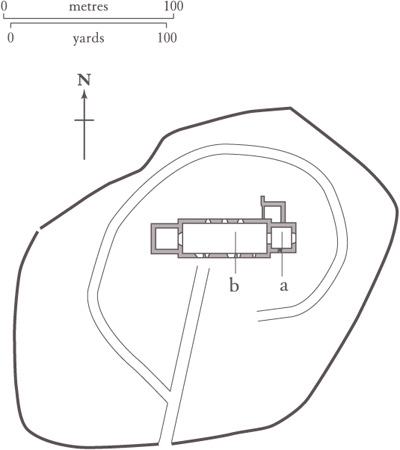

Figs 9 and 10 St John the Evangelist, Escomb, County Durham; the most perfect Anglo-Saxon church in England. Massive Roman stones were used in its construction, including what is probably a re-set Roman arch in the chancel. Fragments of stained glass have been found and the windows have grooves for shutters. A patch of cobbled flooring in the nave is probably Saxon. The plan shows its original layout as revealed in excavation in 1968. The walled circular churchyard was a very early addition. a) chancel; b) nave.

Wearmouth and Jarrow have been extensively investigated, and enough remains to demonstrate that the layout of Benedict’s buildings was influenced by what he had seen in Gaul and elsewhere. In plan both sites were based on continental monastic models. The churches were long, narrow (their length three times their width) buildings with a western porch. Either side of the nave were lower porticuses or galleries, giving the buildings a basilican appearance (that is to say, a taller nave with lower aisles).

The church at Wearmouth had a narrow, 100ft-long, roofed gallery with glazed windows linking it with the domestic structures (fig. 8).

This feature, a precursor of the monastic cloister, presumably used for reading, writing and exercise, is a feature Benedict could have seen on his travels. Yet despite all this novelty the church, and particularly the domestic buildings, refectory and dormitory, were very similar to large, secular, timber structures elsewhere in Saxon England. At the royal site of Yeavering, for instance, a timber church was excavated that was virtually identical in plan and size to the Wearmouth and Jarrow churches.18

Fig. 11 St Andrew’s, Greensted-juxta-Ongar, Essex. In Norway numbers of timber churches survive, but this is the sole early medieval survivor from thousands of such churches in England. While the walls are of the late 11th century, the brick sill on which they sit is of 1848 and the dormers and brick chancel are Tudor. The tower is later too.

Although conceived in a timber-built tradition, these Northumbrian churches were among the first to be built in stone since the disappearance of the Roman legions two hundred years earlier. This is important, as stone building was associated by early Saxon Christians with Roman Christianity. When King Nechtan of the Picts accepted the Roman Easter he asked the Northumbrians for advice, not only on liturgical issues, but in building churches in masonry ‘after the Roman fashion’.19

A visit to the church of St John at Escomb, County Durham, still conveys a sense of what the churches at Wearmouth and Jarrow must have been like inside (figs 9–10). This is the best-preserved stone church of the early Saxon period in England, but its chiselled stone walls cannot do justice to what we know of the original interiors. Walls were plastered and painted white, carving was picked out in bright primary colours, the walls were hung with icons and the windows filled with stained glass.

Wearmouth and Jarrow are the only early Saxon monasteries about which anything is known architecturally. We do know, however, that as well as the monasteries of Northumberland and Kent there were many others in the Midlands, the Thames valley and the west. But before about 950 only the largest were of stone; most were still built of timber by people working in local building traditions.

At Greensted-juxta-Ongar, Essex, there is a remarkable survival: St Andrew’s is the single surviving Anglo-Saxon timber church in England (fig. 11). Thanks to dendrochronology it is now known that most of its surviving timbers date between 1063 and 1100. Yet this building was constructed in the same way as hundreds of other much earlier examples, somenow revealed through archaeology. The walls were built of split oak logs with their rounded face on the outside and fixed together with concealed timber tongues. These are jointed into timber roof and base (sole) plates, making a rigid wall.20

As the Roman legions left the shores of Britain they took with them the know-how and infrastructure necessary to build in stone. For the next two hundred years rich and poor, strong and weak, pagan and Christian lived, worked and worshipped in timber buildings. Some of these were in a long tradition of native building stretching back to the Iron Age; others were introduced by Anglo-Saxon settlers; most were an eclectic blend of Romano-British and Germanic engineering and aesthetics. At the high end these were buildings of considerable sophistication and magnificence; at the lower end buildings of extreme functionality. It was the coming of Christianity that reconnected England with the stone-building traditions of Rome. As a result, English architecture acquired a distinct and vibrant character – a blend of native, timber-based building and stone-built Roman styles. This is what the Viking raiders of the 790s found when they started their systematic plunder of the kingdom of Northumbria. These attacks, and their political and economic effects, set English architecture in important new directions.

Fig. 13 Offa’s Dyke, Clun, Shropshire, a massive piece of military engineering begun soon after 757. It stretched from sea to sea, and for 200 years kept the marauding Welsh out of Mercian England.