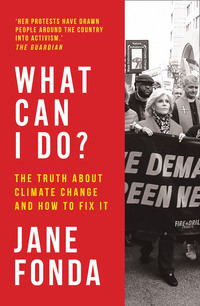

What Can I Do?

This is exactly the kind of brave leadership we need to see from our next president, and there are very smart policy experts putting together a first-ten-day plan for that president, laying out things he can do through executive order without waiting for Congress. This will be a huge, disruptive, superambitious undertaking, and yes, it will cost a whole lot of money. But the cost of inaction is huge. Over the last three years, the total cost of billion-dollar weather and climate events exceeded $450 billion! And the COVID-19 pandemic has shown us that government can find the necessary money in an emergency.

The same interests that hated the New Deal are the ones today telling us that the Green New Deal is bad, that Big Government is bad, and they’ve convinced a lot of people of this, the very people who are actually hurt because government is being shrunk and taken over by corporate interests.

The fact is, the policies proposed by the Green New Deal are in line with what the American people have done before … because there was no choice.

There is no choice now.

“In Philly over a hundred people have died in the last ten years during heat waves. They send us home from school, but most kids go back to homes without air-conditioning and neighborhoods that are 10 degrees hotter than in the suburbs,” she said.

Abigail described an oil refinery situated in a densely populated poor neighborhood where large numbers of children suffer from asthma. That refinery exploded in 2016, raining down debris on the homes of South Philly. Although no one was killed, the disaster released five thousand pounds of hydrofluoric acid into the air.

“In Philly people die because of fossil fuels, because we don’t have nurses in public schools, because they are poor. Young people are born poor, stay poor, and maybe die later from a heat wave or a fossil fuel explosion that they had no role in creating.

“My friends have a running under-the-green-new-deal joke: Every time we think of something so good it feels impossible, we make the joke. Under a Green New Deal, corporate bookstores are public libraries. Under a Green New Deal, we’re going to turn all these gas stations into parks. Under a Green New Deal, all the public schools have air-conditioning. It’s mostly a joke, but it’s also not.”

I found Abigail’s words heart wrenching.

Jasilyn Charger spoke next. She was one of the indigenous youths who had run two thousand miles from Standing Rock, North Dakota, to Washington, D.C., in 2016 to deliver a petition with more than 140,000 signatures to the Army Corps of Engineers asking them to stop building the Dakota Access Pipeline through their lands and waters. She, too, questioned why young people have to be on the front lines of the climate crisis instead of “living our lives as young people. It’s because we feel the fear in our hearts and souls that our future is threatened. But today, just to see that we’re supported by the young and the old, by the rich and the poor, standing united as one, on a field in front of the Capitol building brings so much strength to my heart.”

The next speaker, Charlie Jiang, a twenty-four-year-old climate campaigner at Greenpeace USA, had wanted to be a physicist to uncover the mysteries of the universe and had expected that he would lead a comfortable life.

Jasilyn Charger speaks.

“But in the face of a crisis where so many of my friends and family are suffering from pollution and fire, comfort is no longer an option for people like me because first and foremost, as global citizens, we have a duty to each other and I had to ask myself, how could I look at the stars as a physicist when so many people are suffering on this planet?”

Charlie said a new age of a Green New Deal was possible if millions of people come together, take to the streets, vote, and engage in civil disobedience.

“The next decade is going to be crucial, and the next year will be crucial. We’re going to need all hands on deck in 2020 to take bold actions so that we can elect leaders who will be champions for a Green New Deal and pass policies to end the era of fossil fuels.”

Charlie Jiang speaks.

I concluded the rally imploring people to vote. “Make sure that you’re registered to vote. Make sure that everyone you know is registered to vote. When the time comes to vote, reach out to people who may not be able to get to the polls and drive them to the polls. Every vote counts. And I’m not just talking about the president or the Senate or the House but state legislatures, governors, boards of supervisors, every one of the elected officials that you can vote for can make a difference. And before you vote for them, find out how they feel about the climate crisis. Make sure that they understand the urgency that’s involved because who we elect next November is going to be so important. And then you have to mobilize. Think about the original New Deal in the 1930s. Realize that what got Roosevelt to do what he did, that really brought this country out of despair in desperation, was because people were in the streets. They forced him to do it. Demonstrate. Organize. Vote.”

Our march from the rally to block the intersection between the Capitol and the Supreme Court was chaotic as reporters pressed in, shoving microphones in our faces. It seemed as if they were five-deep on all sides. Most were friendly, but there were also the “Jane, did you take a plane to get here? Don’t you think that’s hypocritical?” and “Hanoi Jane, why do you think you can speak about climate?” I refused to engage. My daughter, Vanessa Vadim, surprised me by taking the train down from her home in Vermont to be with me. One of my closest, longtime friends, the film producer and curator of the Tribeca Film Festival Paula Weinstein, had come, too. They were so buffeted about by the cameras pressing in from all sides, it was hard to keep moving ahead, in a line, chanting and holding the six-foot-long “Green New Deal” banner.

All of them, Vanessa, Paula, Sam, and the actor Katherine LaNasa along with twenty or so others, planned on engaging in the civil disobedience. I was supposed to receive the Stanley Kubrick Britannia Award for Excellence in Film that Friday, but I knew I couldn’t attend the ceremony because Fire Drill Fridays were my priority. As I was being led away by the police with my hands in ziplock cuffs, I was filmed shouting, “Thank you. I’m honored!”

A MODERATE’S VIEW OF CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE

Sam Waterston

“I came out of getting arrested a different person than I went in. Pieces of myself came together that were being held apart by dread of—if I faced it—how much bigger than me the climate problem was going to be and denial, the old delusion that if you stick your head in the sand, the problem will go away or, at least, not land on you. As I’ve said before, I’m not a radical. In a radical situation, though—and the climate emergency is a radical situation—radical action is the moderate thing to do. To even feel a little bit whole, we need to do something out of the ordinary about it. Getting arrested over any cause was completely new to me. So far in my lifetime, there have certainly been other issues that merited it, but the climate emergency is at the top of any list. Of course, we all need to be modest about what we as individuals can accomplish, but getting arrested might actually work! Everyone should try it. As always, Abraham Lincoln hit the nail on the head: ‘We must think anew, and act anew, and then we shall save our country.’ That’s what it feels like to get arrested over the climate emergency: thinking, and then acting, anew. I can’t recommend it highly enough.”

Apparently, the clip was enthusiastically received at the gala event. I hoped it would inspire more celebrities to join. Whether we like it or not, our society is very celebrity focused, and having a famous person publicly join a movement helps bring the press out and expand the reach of the message. The passion and life-changing commitment of the students moved and inspired me deeply. By bringing celebrities together with these youth leaders and climate activists, Fire Drill Fridays was helping to amplify the voices that needed to be heard.

This time, because there were more of us, instead of being held in the cells inside the police station, we were taken to a large, cold warehouse used for processing by the police for these types of occasions. I kept an eye on Sam, who was chatting with some of his fellow detainees and seemed in fine fettle. I knew Paula would be okay. As an anti–Vietnam War activist in the 1960s and 1970s, this was far from her first encounter with the Capitol Police.

I met interesting people during our three hours of detention: a manicurist from Delaware who had heard about Fire Drill Fridays on the radio and had come with her daughter, neither of whom had ever done anything like this before; a professor of rhetoric from a midwestern university who had a bit of Diane Keaton humor in her; and a Pakistani woman who works to protect Muslim refugees from ICE.

It was still daylight when we paid our $50, gave our thumbprints, and were released. There was a contingent of young climate strikers along with our jail support team waiting for us. I could see that Sam had been affected by the whole experience in a positive and deep way.

A few weeks later, Sam, the self-described moderate who had never engaged in civil disobedience or gotten arrested until our second Fire Drill Friday, had joined the students protesting their university’s fossil fuel investments during halftime at the Harvard-Yale game and gotten arrested on the field. He sent me a photo someone took of him in handcuffs looking up with a big grin. “Now look at what you’ve done!” And Sam came back to D.C. with his sister Ellen for the twelfth Fire Drill Friday and did it again.

Vanessa was off to visit some friends, so Paula and I joined Jerome at his weekly climate strike at the While House.

I could feel my voice starting to weaken, so I left the chanting to Jerome and was amazed at his vocal stamina and persistence. He stood there, shouting climate chants for at least thirty minutes while I engaged with people who stopped by for selfies and talked about the climate crisis until it was time for us seniors to call it.

It was the end of another week, another Fire Drill Friday under our belts. I could feel it was growing.*

What Can I Do?

The surge of public interest in a Green New Deal is so exciting! Finally, we’re talking about a response as ambitious as the science requires. The Green New Deal resolution, introduced by Senator Ed Markey and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, is just the start. There is much work ahead to fill in the details, build support, and then make it real. There are many ways to get involved.

With gridlock in the Senate and White House stalling meaningful federal action, we will likely see more progress on Green New Deal policies at the state and city levels. Many states and cities are working on Green New Deals tailored to their specific needs. The GND in Seattle—known for its terrible traffic—includes free public transit. California has a statewide GND act that proposes strong action on climate while increasing affordable housing and addressing homelessness, which is a crisis in the state.

Many local governments are advancing the GND, even if they don’t use that name. About twenty states and a hundred cities have plans to achieve 100 percent renewable electricity. So check out if there is a GND initiative—whether named GND or not—where you live. If not, gather friends or contact a local climate group to write to your city and state representatives to urge them to get going. Organize community dialogues to identify what is necessary to start a GND where you live.

The GND plan your city or state develops will be better, and support higher, if diverse stakeholders, including labor and environmental justice groups, are engaged from day one. The New Consensus has useful materials for building unanimity around a Green New Deal; see its website for the different components of a Green New Deal and build one that suits your community. The Sunrise Movement has loads of opportunities for young people to get involved locally and nationally, including a guide for starting a local group to work for a GND. Sunrise’s website lists the U.S. Senate and congressional co-sponsors of the GND resolution: Check if your representatives are there. If not, write and call them—and recruit friends, too—to rally support.

Many communities are building on the Green New Deal: Indigenous activists with the Red Nation have a Red Deal that incorporates Native leaders’ wisdom, ocean advocates are crafting a Blue New Deal to protect our oceans alongside a GND, and feminists have developed a set of feminist principles for a Green New Deal. Discuss incorporating these ideas—or others—into the GND campaign you join or start.

When you’re putting together a Green New Deal package for your community, don’t forget transitioning off fossil fuels! That means stopping the permitting of new fossil fuel operations, responsibly winding down existing operations, and ensuring those whose fossil-fuel-dependent jobs get eliminated find good work elsewhere. A GND that advances equity and security for all has the power to steer our country toward true prosperity as we address the climate emergency.

Of course, we’re not going to get a GND passed if we don’t elect climate leaders at all levels of government. Ask every candidate—for president, governor, mayor, city council, zoning board, planning commission—every single one—if they support a Green New Deal. Let them know that you support climate leaders on Election Day—and every day! Ensure that friends, neighbors, and co-workers are registered, and then let’s all get out the climate vote!

Ted Danson gets arrested.

CHAPTER FOUR

Oceans and Climate Change

The week leading up to our third Fire Drill Friday was probably, physically, the hardest week of all for me. On Saturday, I flew to California, where Lily Tomlin and I had contracted to do five speaking engagements in the Los Angeles area. On Thursday, I hosted the teach-in remotely via webcam and planned to take a red-eye back to D.C. so that I could arrive in time for the Friday rally. Red eyes and I don’t get along very well.

This Fire Drill Friday was especially emotional. You see, the first two focused on why I was doing them, what our demands and goals were, and what we saw as the solution. This week I was studying the effects of climate change on our planet, starting with oceans. My stomach was in knots.

I grew up in Brentwood, California. For my first decade of life, before the emergence of freeways and smog, I could see every day from our house in the hills a wide, shimmering expanse of ocean that inspired my little tomboy self. I spent summers at the Santa Monica beach learning to dive under waves and bodysurfing with my brother. I have snorkeled on the Great Barrier Reef while it was still fully vibrant and thriving. I’ll never forget my first plunge off the wing of a seaplane far out at sea where there were no other people except my son and daughter. The wild variety of colors and shapes so startled me I almost swallowed a mouthful of water. I’ve been scuba diving with my children over coral reefs in the Caribbean and with sea turtles and seals in the Galápagos Islands. I’ve fished the high seas with every important man in my life, starting with my father. I spent ten years with Captain America, Ted Turner, who sailed every ocean on earth and won the America’s Cup race. His respect and love for the ocean was contagious. The idea that my grandchildren won’t have coral reefs to snorkel over because of climate change breaks my heart. Learning how much damage we have already done to the ocean, and how that destruction is accelerating, made this Fire Drill Friday urgent and personal.

Although I have loved the ocean all my life, I found there was a lot that I did not know about it, and I was ready to learn from our Fire Drill Friday experts.

The Teach-In

John Hocevar, the oceans campaign director for Greenpeace, joined us for our teach-in, and what he told us was eye-opening.

“The ocean absorbs 93 percent of the heat we generate and roughly 40 percent of the carbon dioxide we produce,” he said. “In fact, oceans are our biggest allies in the fight against climate change. What will happen if we are not able to reverse the damage we’ve done to them? Our climate crisis will continue to accelerate.

“People have eaten roughly 90 percent of the world’s big fish, which means that it’s difficult for fishing companies and seafood businesses to turn a profit. So many of them have cut costs by not paying their workers a living wage. Some have stopped paying their workers at all.”

John told us that they are seeing human trafficking, forced labor, debt bondage, and slavery on fishing boats.

“Besides the human labor abuses and the issue of overfishing,” John went on, “there’s the problem of the bycatch, which includes accidentally, or sometimes not so accidentally, catching a million sharks and hundreds of thousands of sea turtles that die in fishing gear each year. An important organization advocating for oceans, Oceana, estimates that overfishing, bycatch collection, and the demand for shark fins for soup kill 100 million sharks a year.

John Hocevar speaks. Behind him is Ted Danson.

“Did you know that for three billion people about 20 percent of their essential protein comes from the ocean? Did you know that about half of the oxygen we breathe comes from the ocean? Actually, that oxygen is generated by microscopic plants known as phytoplankton. These vital plants are one of the first casualties of the way climate change is acidifying oceans.

“As we burn coal, oil, and natural gas, carbon dioxide goes up into the atmosphere and warms our planet, causing climate change. That’s global warming. But a lot of that carbon dioxide is absorbed directly into seawater, increasing the acidity of the water. That added acid makes it difficult for organisms like clams and oysters and coral reefs to form calcium skeletons.

“Possibly the most serious consequence of all,” John said, “is its effect on plankton and phytoplankton, the small creatures that comprise the bottom of the food chain, feeding everything from tiny fish to giant whales. Most plankton, including the oxygen-producing phytoplankton, can be damaged by the acidification of the ocean water. They’re already starting to be degraded, and some have disappeared.

“What’s going to happen when we lose whole classes of plankton?” John asked. “We don’t know. But our oceans are already producing less oxygen than they were just a few years ago. We’re conducting an uncontrolled experiment in the open oceans at a global scale, and it’s not okay.

“Offshore drilling is a big part of what’s driving climate change right now,” John continued. Offshore drilling degrades the environment, and oil spills and burning of oil extracted from the ocean are big factors in climate change. John described the direct effect one oil spill had on wildlife. “After the Deepwater Horizon explosion in the Gulf of Mexico, I was there on the Greenpeace ship Arctic Sunrise, working with scientists to determine the scope and impacts of the disaster. What I saw, the impacts on seabirds, upon dolphins, on really everything that swims and crawls in the Gulf of Mexico, gave me nightmares for weeks. And again, this is not okay. We can’t just let this keep happening.”

At the teach-in, we were also lucky to hear from Ted Danson, who has spent decades of his life fighting for the world’s oceans. It’s unusual for a major celebrity to be somewhat of an expert on something like oceans, but Ted Danson is, which is why I scheduled this particular Fire Drill Friday at a time when he was free to join.

“Basically, one-third of the world’s catch is being thrown overboard,” Ted said. He explained that seventeen years ago, in 2002, when he merged his American Oceans Campaign with Oceana, where he now serves on the board, they focused on the serious problem of overfishing and bycatch. “Fishing boats used to have to lift their nets over rocks, not to protect these fragile fish habitats, but because they didn’t want to tear the nets. But when their engines got more powerful, at least for the large trawlers, they had enough power to drag their huge nets on rollers along the bottom of the sea, destroying the seafloor habitats, turning it all into gravel pits. And, as John said, when they pull these enormous nets up, they are filled with all kinds of sea animals that they were not fishing for, which they throw overboard.

“Our message at Oceana became ‘Save the Oceans, Feed the World,’” Ted said. “We work with the fishing management systems in the twenty top coastal countries and get them to start fishing sustainably. The people who have investments in the huge trawlers fight us, but the locals understand that if you manage fisheries correctly, there’ll be more fish, more money, more jobs, more food. That’s been proven time and time again. And most of the fisheries and the nurseries are in that first two hundred miles of every country’s economic zone.”

John reminded us that though the coastal waters were important, to save the sea turtles, the whales, the seabirds, and the tuna, we had to take care of the high seas, too.

“These are all species that migrate across the world’s oceans. And right now, unfortunately, the high seas are poorly regulated, basically unprotected, and it’s the Wild West out there and there’s pirate fishing. We’re going to lose things in our coastal waters even if those are well managed.”

“Come on, John,” I pleaded, “give us some good news. I feel like putting my head under a pillow and crying.”

And he did. He told us that ocean advocates have had some real success stories recently and that in the summer of 2019 more than 190 nations came together through the United Nations to start negotiating a Global Ocean Treaty to establish ocean sanctuaries that will help preserve and grow ocean life. Sanctuaries are the most proven, cost-effective tool to rebuild depleted populations of fish, to protect biodiversity, and to increase the resilience of species and ecosystems so they have a better chance of surviving the impacts from climate change, plastic pollution, and ocean acidification.

“If we get this right,” he said, “and we have to get this right, this treaty is going to enable us to scale up ocean sanctuaries that actually will be able to fully protect 30 percent of the world’s oceans from extractive use for the first time. Right now, we have about 2 percent of the oceans fully protected and about 5 percent partially protected, but scientists say we really need to get to 30 percent or more by 2030.”

Ted shared some more good news about protecting fish stocks. Oceana has teamed up with Google and a satellite company called SkyTruth for an oceans surveillance program called Global Fishing Watch, partially funded by a generous donation from Leonardo DiCaprio. Every ship over three hundred gross tons traveling on international waters, ships that can be three hundred feet long and are capable of processing 350 tons of fish a day, has to have a device that lets a satellite know where it is and where it’s been. When a ship sails swiftly through a protected marine sanctuary, you know it’s going someplace else to fish. But if all of a sudden it slows down and zigzags, you know that the ship is probably fishing illegally. By notifying someone onshore when the ship docks, authorities can search it and hold the wrongdoers accountable. It’s tricky, though. Some of these ships get refueled on the high seas, where they off-load their often-illegal catch onto another boat. If a search of the ship onshore determines that it is not just fishing but engaging in human trafficking, drugs, and gun smuggling, activists can take this information to the ship’s insurance company and ask, “You know that ship that you insure? Here’s proof of all the illegal things taking place on board. Are you sure you want to insure that?” Without insurance, the ship cannot legally operate.