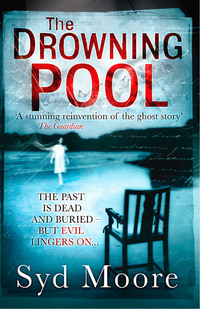

The Drowning Pool

Syd Moore

The Drowning Pool

Dedication

For my boys Sean and Riley. And for Liz, undoubtedly causing havoc in the heavens.

I am hugely indebted to Kate Bradley, without whom The Drowning Pool would have never seen the light of day. I would also like to add to the long list of people I owe thank yous: Keshini Naidoo and the incredible team at Avon; Father Kenneth Havey, for his advice on the Robert Eden extracts; Cherry Sandover, for her introduction; Ian Platts for his; Clair Johnston for her research into Sarah Moore; Simon Fowler for his excellent photography; Harriett Gilbert, Jonathan Myerson and my tutors on the Masters in Creative Writing at City University, and the esteemed writing group that developed from it; Steph Roche for her unstinting support and late night chats; my friends and family, especially my dad for ensuring I always strive to do better and my mum, for keeping the faith.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Extract from White’s Directory of Essex 1848

George Gifford, A Dialogue Concerning Witches and Witchcraftes 1593

Chapter One

The night it happened Rob, a friend of Sharon’s, was…

Chapter Two

That June was one of the hottest we’d had for…

Chapter Three

Looking back, all the signs were there. Human beings have…

Chapter Four

When I woke I was moody and morose. Though I…

Chapter Five

My computer screen flicked on. I fingered the scrap of…

Chapter Six

It’s difficult in retrospect to try and describe how I…

Chapter Seven

As it was, on the Thursday, nothing happened. I psyched…

Chapter Eight

The storm was on everyone’s lips that day. When I…

Chapter Nine

The conversation with Marie had been pretty sobering. Inside it…

Chapter Ten

I’d forgotten that this weekend was the annual Leigh folk…

Chapter Eleven

The Old Town was packed. Sunday was the less traditional…

Chapter Twelve

The holidays stretched before me like a lazy cat. Although…

Chapter Thirteen

The Records Office was an odd-looking modernist structure set in…

Chapter Fourteen

The other day I found the book I had been…

Chapter Fifteen

Sharon’s untimely collapse that night proved fortunate, at least for…

Chapter Sixteen

My head was beginning to ache as I put down…

Chapter Seventeen

I was woken at ten by a text from Martha.

Chapter Eighteen

I arrived in good time for my appointment, hoping to…

Chapter Nineteen

When I got home I was knackered but there was…

Chapter Twenty

The view over the town square was awe inspiring. Andrew…

Chapter Twenty-One

Tobias Fitch was propped up on his bed. The stroke…

Chapter Twenty-Two

We said our thank yous to Claudia and Laurens, refusing…

Chapter Twenty-Three

It was only later, when we sat back at the…

Chapter Twenty-Four

I suppose the first thing that alerted me to the…

Chapter Twenty-Five

Puzzles have never been my strong point. Even when I…

A Note to the Reader

Read On

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Extract from White’s Directory of Essex 1848

LEIGH, a small ancient town, port, and fishing station, with a custom house and coast-guard, is mostly situated at the foot of a woody acclivity, on the north shore of Hadleigh Bay, or Leigh Roads, opposite the east point of Canvey Island, in the estuary of the busy Thames, 4 miles West of Southend, 5 miles South West of Rochford, and 39 miles East of London. The houses extended along the beach are generally small, but there are several neat mansions, with sylvan pleasure grounds, on the acclivity, which rises to considerable height, and affords, from various stations, extensive prospects of the Thames, and the numerous vessels constantly flitting to and fro upon its expansive bosom. The trade consists chiefly in the shrimp, oyster, and winkle fishery … Besides great quantities of oysters in the season, nearly a thousand gallons of shrimps are sent weekly to London. The boundary stone, marking the extent of the jurisdiction of the Lord Mayor of London, as a conservator of the Thames, is about 1½ mile east of Leigh, on a stone bank, a little below high water mark, and it is annually visited in form by the Corporation. Lady Olivia Bernard Sparrow is lady of the manor of Leigh, or Lee, which was held by Ralph Peverall at the Domesday Survey, and afterwards by the Rochford, Bohon, Boteler, Bullen, Rich, and Bernard families. Three copious springs supply the inhabitants with pure water, and the parish contains 1271 inhabitants, and 2331 acres of land, including a long narrow island, called Leigh Marsh, between which and Canvey Island, are the oyster layings. A fair for pedlery etc., is held in the town on the second Tuesday in May.

The Church (St. Clement) is a large ancient structure, near the crown of the hill, and has a lofty ivy-mantled tower, containing five bells. It has a nave, aisles, and chancel, in the perpendicular style, and the latter is embellished with two painted windows, carved oak stalls etc., and contains several handsome monuments. The nave is neatly fitted up, and has a good organ, given by the present incumbent. The rectory … is in the patronage of the Bishop of London, and incumbency of the Rev. Robert Eden, who is also rural dean, and has erected a handsome Rectory House in the Elizabethan style. The tithes were commuted in 1847. The Wesleyans have a chapel here, and in the town is a large Free School, attended by about 170 children, and supported by Lady O.B. Sparrow, who established it about 16 years ago, for the gratuitous education of children of this parish and Hadleigh, in accordance with the principles of the Church of England.

George Gifford, A Dialogue Concerning Witches and Witchcraftes 1593

‘Truly we dwell in a bad countrey, I think even the worst in England … These witches, these evill favoured old witches doe trouble me … they lame men and kill their cattle, yea they destroy both men and children. They say there is scarce any towne or village in all this shire, but there is one or two witches at the least in it.’

Chapter One

The night it happened Rob, a friend of Sharon’s, was down by the railway tracks walking his dog. He said the lights and the shrieking freaked the terrier and started it barking. I don’t remember hearing it. But he heard us. ‘You were making enough noise,’ Rob said, ‘to wake the dead.’

Which is kind of funny as that was exactly what we were doing.

Though, to be honest, we were so hammered none of us noticed the mist or a slip of shadow darting between us. We just wanted to carry on boozing. I used to think if they ever made a film of my life, that’s what they’d call it. Though obviously now it’d have a very different title. Drag Me to Hell could be a contender.

Just shows you how much has changed.

Sitting here by the window, the chill kiss of autumn is on my cheek. Watching the dried lemon sunlight slanting across the room, summer feels like another world away. It’s pretty difficult to get my head round what happened. But that’s where this comes in: getting it out of my brain and onto paper, where it can be nicely controlled, explained and edited. To make sense of it before it dissipates and I forget it altogether. That’s what they told me would happen.

Yet the making sense of it irks me so. Can one actually make sense of the senseless? Certain things happened because of bad luck, plain and simple: wrong person, wrong time, wrong confidence, misplaced trust. Call it chaos theory, the butterfly effect, or my personal favourite the shit happens model. You can’t explain it because, from time to time, bad things happen just because they do.

I guess quite a lot of it comes under that heading.

But then there are those other experiences that can’t be categorized or rationalized either. Yes, shit happens but weird stuff does too. Good weird stuff. Coincidences or what Jung called synchronicities – two or more events seemingly unrelated that happen together in a meaningful manner. I know that happens. Doesn’t mean it’s easy to make sense of though. You’ll see what I mean.

‘You’ll forget’. That’s what they said. Makes me laugh. As if I’d ever forget this. Sure, there’s a massive part I want to blot out as quickly as possible. Believe me, I’ve got stuff up here that would scare the crap out of the general population. But there’s another part I want to keep. A part that’s so jaw-droppingly amazing that it blows your mind if you think it through.

Not that I can yet. Not being so close to it. I have to protect what’s left of my sanity (and many would say that was debatable before all this happened). So I’ll be getting through it bit by bit. Jotting it down. Before it goes.

I’m rambling.

Come on, Sarah. Get straight. Start at the beginning.

Put it all in. Who was there?

I think there were four of us:

First there’s Martha. She’s lovely. A highly skilled landscape gardener. Mum of two, partial to Spanish reds and the odd recreational drug. Big house, nice husband. Fairly content but misses the rave scene.

Then Corinne, who I met in the park – my Alfie was playing with her Ewan. We started chatting and that was the beginning of some serious binge drinking that commenced with the chilli vodka she’d brought back from Moscow, went on to red wine and never really stopped.

Corinne is some kind of hot-shot in local government. The Grace Kelly of our circle. She brings to parochial politics what the American movie star conferred on pug-faced Prince Rainier: glamour, darling. Corinne is blessed with unspeakably good taste in clothes, a sleek platinum bob, supermodel looks and the drinking capacity of a Millwall fan. Lucky cow. That evening she had managed to palm off her boys, Ewan and Jack, on her renegade husband and was well up for enjoying a rare moment of liberty. I think it was she who suggested the castle. She was desperate for a session.

So was the only childfree one of us, Ms Sharon Casey. She and Corinne had been friends for decades. Sharon did something that earned her a lot of dough in the city though I was never sure what. Corinne hinted it was to do with telecommunications but was hazy on the details. I think it involved deals, hospitality and a great deal of stress. That night Sharon had become newly single. I think she’d been dumped though she never said specifically; you could tell something was up. She was on a mission.

And that was it, I think. Oh, apart from me. My name is Sarah Grey, and that is a very important part of the puzzle.

It had started with a quiet drink in the local pub. Third round down and we were getting lairy. Sharon, drunk as a skunk when she turned up, waltzed past our table wearing a massive ‘birthday girl’ medallion. It wasn’t her birthday. Corinne reckoned the staff were giving our table some filthy looks, but for a while we just carried on. We were enjoying ourselves.

Back then, I got so much pleasure from the fuzzy softening that inebriation brought. We all did. It really bugged me when people started going off about it being a prop or insinuating you were running away from things. Of course we were. Life was hard. Being a mother was hard. Being a widow was harder. In the constant juggle of life, work and family, was it too much to ask for a couple of hours of solace and fun? That’s what the wine fairy was bringing that night and to be honest, none of us gave a toss about what the bar staff thought. It was a pub for God’s sake.

It was only when Sharon knocked into a couple of regulars and smashed a glass that we finally did the sensible thing – slurred out some abuse loudly, hit the toilets, grabbed aforesaid sloshed mate and left.

Outside the air felt balmy and there was a buzz on the Broadway. Groups of women were roaming the street in short dresses and sandals. A lot of the older guys were wearing light-coloured linens. A bunch of EMO kids hanging out by the library gardens had thrown off their black hoodies and were larking about on the benches. It was one of those early summer evenings that nobody wanted to end.

So we’re standing there and one of us, I can’t remember who (oh God, has it started?). It was probably Corinne, she’s the organized one. Yes, Corinne suggested we get some bottles from the offy and walk up to the castle. It’s not the kind of thing we would usually do, but like I said, there was something in the air. The sun hadn’t yet sunk beyond Hadleigh Downs so there was still enough natural light to navigate the footpath.

I made a slight detour to my house, which was on the way, and grabbed a blanket while the others bought wine and plastic cups. Within forty-five minutes we were sat on the bushy grass in the shadow of Hadleigh Castle. Well, I use the term ‘castle’ but that’s an exaggeration. It’s been around since the thirteenth century but it’s little more than a ruin: one and a half towers and an assortment of old stones.

As dusk ebbed into night I could just make out, to my left, the tiny white specks of boarded fishermen’s cottages that speckled the dark slopes of Leigh, from the jagged tooth tower of St Clements church at the crest of the hill down to the cockle sheds on the waterfront. Scores of miniature boats nestled in the cradle of the bay.

Around us the hawthorns of Hadleigh whispered in the breeze, like softly crashing waves.

Corinne suggested we build a fire. Her husband, Pat, is into that survival rubbish and she gets dragged out to wooded places in the rain. Pat thinks it’s character building for the boys but he can’t deal with them on his own, so he bribes Corinne to accompany them with vouchers for The Sanctuary. Consequently, she has deliciously smooth skin and a talent for coaxing fire out of the most stubborn wood fragments and twigs.

As the last of twilight disappeared she did herself proud, which was perfect timing because the moon was on the rise now and the air had chilled. There were no clouds and, away from the fug of orange streetlights, out there on the hunchbacked hill, the icy light of the summer constellations was clear and bright. Moon-shadows were everywhere.

The tide had come in around the marsh of Two Tree Island and the gentle ‘ting ting’ of moored boats drifted up to us from Benfleet Creek. Across the estuary the pinprick lights of North Kent villages blinked like hundreds of tiny nervous eyes.

I remember Sharon saying how much she loved the view. Apart from the industrial plant on Canvey Island. ‘That’s a bloody eyesore,’ she said.

Martha threw a fag butt into the fire and said, ‘I like it. It’s a contrast. Industry versus Romance.’

‘It’s ugly,’ Sharon answered. ‘This place is a Constable painting. Then you see that. It’s horrid.’

People always got this wrong. True, Constable captured the castle in oils. I saw a sketch of it at the Tate. But it wasn’t one of his romantic idylls. Painted after his wife’s death, he had picked out browns the colour of crumbling leaves, livid raven blacks, dismal ash greys. The castle, a skeletal ruin, was desolate and alone. And the sky was strange. If you looked at it closely you could see Constable’s brushstrokes were all over the place. The air was turbulent, full of dark storm clouds pregnant with terrible power.

Like something was in them. Waiting to come through.

I sensed that when I first saw the picture and I just know Constable felt it too.

Back then, in the 1820s, she would have been young and beautiful. She used to wander there often to escape the town. Maybe they met. Perhaps her story moved, horrified him?

So Sharon blah blahs about the rural prettiness being scarred and Martha’s on about nature versus industrialization, then I say something about how the biggest chimney, which has a ball of gas burning above it, reminds me of Mordor. The Eye of Sauron, to be precise. ‘I kind of like its otherworldliness,’ I said.

And Sharon went, ‘Ooh. Hark at you, Mrs Spooky.’ And everybody laughed. I don’t know why. I never do generally. ‘I don’t mean it frightens me.’ I knew I sounded like a petulant teen – the wine had fired my blood. ‘There’s plenty of other things round here that do.’

Sharon must have heard my indignant tone cos she got straight in and pacified me with platitudes. ‘Yeah. Yeah,’ she said. ‘I know. Not all the local history’s quaint.’ She shot a look at Corinne. ‘Isn’t this place meant to have something to do with some old Earl’s murder?’

We all looked at Corinne, who shrugged. Though not related, Sharon and Corinne’s families were inextricably intertwined in the way that happens when generations are content to live in the same place for a good length of time. Corinne came from a very old Leigh family so we automatically deferred to her on local matters.

‘Probably,’ she said. ‘I know a mysterious lead coffin was set down on Leigh beach around that time. Some locals had it that it was a murdered nobleman. My dad always said inside it was the body of Thomas, Duke of Gloucester, who had been killed by Richard II’s men in Calais. He was strangled with a sheet so violently that his head was severed. The coffin was whisked up to the castle. The next day it had vanished.’

‘How awfully sinister,’ said Martha, and took a long swig of her wine.

Sharon coughed on her fag and told everyone the St Clements steps creeped her out. This was the steep pathway that connected the Old Town on the seafront to the newer part of town higher up. ‘I always feel like I’m going to have a heart attack when I get to the top. And people have done: they used to try to bring the coffins up by a different route, which wasn’t at such a sharp angle. But then some posh bloke built a new house and closed that road off as he wanted a bigger garden.’

‘The Reverend Robert Eden actually,’ said Corinne. ‘And it wasn’t exactly a house. He built a new rectory as the old one was falling down. It houses the library now.’

‘Right,’ said Sharon, completely disinterested. ‘Anyway, everyone in the Old Town had to start using the steps to get the bodies to the church but it was so steep a few of the pallbearers started popping their clogs at their mates’ funerals. Imagine that! My neighbour swears blind Church Hill is haunted.’ She spoke the last words in a Vincent Price style and punctuated the sentence with a wicked cackle.

We all looked at Corinne again. This time she smiled. ‘Perhaps it is. For such a small place, the town has lots of stories. There was Princess Beatrice way back in the thirteenth century. Daughter of Henry III. Obviously she was meant to marry well. Henry had arranged for her to marry a Spanish count but she fell in love with a young man, Ralph de Binley, and ran away to Leigh to elope. Someone found out about it and they caught the couple on Strand Wharf. Ralph was sent to Colchester, accused of murder, but managed to escape back here where he was banished from England never to return. Some say, on clear nights, you can see Beatrice out on the wharf, waiting for her lover, pacing up and down, crying her eyes out.’

I didn’t want melancholy tales on a drinking night and was about to make some kind of glib comment to lighten the tone, but Sharon got in before me. She must have still been raw from being dumped.

‘Pass me the bucket. That’s not spooky. I thought we were doing scary.’

Corinne looked put out again so I grabbed the wine and refilled her. She fixed her grey eyes on me like a cat noticing a wounded pigeon for the first time. Her eyes widened and she paused theatrically, then said, ‘Aha, well if you want a scary story,’ her fingers made a kind of flourishing gesture in my direction, ‘look no further than our namesake here, Sarah Grey.’

I groaned and rolled my eyes. I shared my name with a local character and the pub named after her. There was lots of mileage in this one.

‘The other Sarah Grey,’ Corinne grinned and poked me in the ribs, ‘was a right old witch. Have you heard the tale, Sarah?’

Of course I had. I couldn’t move around the town without someone making a lewd comment about me doing favours for sailors.

But Sharon piped up that she didn’t know the whole story and Martha wanted the gory details, so Corinne drew us closer to the fire and asked if we were sitting comfortably.

‘Then I’ll begin,’ she whispered in a proper storyteller’s voice. ‘What we know is this – Sarah Grey was a nineteenth-century sea-witch who made her living from the pennies sailors threw her for a good wind. She would sit on the edge of Bell Wharf conjuring blessings for those that would pay. Until the captain of The Smack came along. Now he was a zealous man.’

‘What’s zealous?’ asked Sharon and hiccupped. Everyone ignored her.

‘A fervent Christian, he would have nothing to do with witchcraft so he forbade his crew to give her money.’ Corinne licked her lips and lowered her voice further. ‘It was a calm and sunny day when they set sail from the wharf.

‘But as they steered into the estuary, a strong wind came out of nowhere and lashed the boat. The sailors tried desperately to bring the sails down but the wind had entangled them and The Smack was tossed about the waves like a …’ she paused to find a simile.

‘Plastic duck?’ Sharon offered unhelpfully.

‘They didn’t have plastic back then,’ said Martha, opening another bottle of wine. ‘Like a cork perhaps?’

Corinne was irritated. We had broken her rhythm. ‘OK, OK. The Smack was tossed around like a cork.’

‘A cork’s quite small though,’ I said mildly. ‘And a ship’s quite big …’

‘Do you want to hear this or not?’ she snapped.

We muttered apologies and tried to focus.

Corinne cleared her throat and continued. ‘So they’re in this massive storm. One of the crew started shouting, “It’s the witch! It’s the witch!” Suddenly the captain picked up an axe and hit the mast. The sailors watched him thinking he had gone completely mad but when, on the third stroke the mast fell, the wind immediately dropped. When the boat eventually managed to limp home to Bell Wharf, do you know what they found? There, on the side, was the body of Sarah Grey, three axe wounds to her head.’

We made approving noises and raised our eyebrows.

‘That made me shiver,’ said Sharon.

‘Well,’ said Martha. ‘It is a bit cold. You know, Corinne, I’ve heard another ending. Deano’s cousin told me that, yes, the captain had forbidden his men to give her money, so Sarah Grey put a curse on them. The wind came up when they went out to sea and they couldn’t get the mast down but, then he says, every member of the crew but the captain perished. When the captain finally made it back to the shore he swore vengeance on Sarah Grey. The next day her headless body was found floating in Doom Pond, the ducking pond.’

I sniffed. ‘The ducking pond?’

‘Where they used to dunk scolds. Most old villages used to have one: if a woman argued or quarrelled with her husband or neighbours, she’d be strapped into the “ducking stool” and dunked in the water.’

A small piece of wood exploded in the fire, sending sparks over Martha. We all jumped.

Martha brushed them off her jeans and laughed. ‘Is that someone telling me I’m right or that I’m wrong?’

‘I suppose that’s quite likely to be true,’ Corinne said. ‘Who knows? It’s a shame about Doom Pond.’

A relative newcomer to the town I’d failed to notice the pond and asked her where it was.

Corinne’s voice became doleful. ‘Underneath those horrid mock-Tudor flats in Leigh Road.’