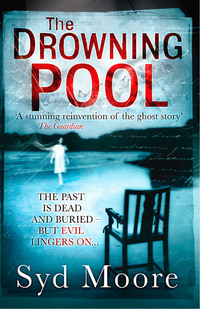

The Drowning Pool

I tried to calm myself by repeating his words – there was nothing to worry about – but already unwelcome images had begun to crowd my head: Alfie alone, Alfie crying, Alfie orphaned. My throat tightened.

‘Do you want me to take a look at this while you’re here?’ He was examining my amateur attempt at a bandage. ‘What have you done?’

My head was still reeling. ‘Oh,’ I said absently, as he came round the side of the desk and began unwinding the fabric, ‘a burn.’

I mustn’t die. Alfie could not lose two parents. To lose one was bad enough. It couldn’t happen.

Doctor Cook was looking at me. ‘… perfectly well,’ he was saying, finishing his sentence with a grin.

I got a grip and spoke. ‘I’m sorry?’

‘I said, whatever it was, it’s healed perfectly now.’ He released my hand.

I looked down: the skin was smooth and pink. There was no sign of the burn.

I picked up my bag and staggered out without saying goodbye.

Later, after Alfie had gone to bed, I phoned Corinne. She couldn’t come over, as it was her au pair’s night off, so we opened our own bottles of wine and sat in separate houses, chewing the fat.

She was a down-to-earth woman. She had to be. Her son Jack was precocious, astonishingly so. Learning his alphabet at three and reading Enid Blyton on his own by five. Now, at eight years old, he was studying GCSE text books.

At the other end of the scale Ewan was a hyperactive four-year-old. Pat worked in sales and was often away for several weeks at a time, while Corinne managed the house, the bulk of the childcare and a full-time senior job in local government. Help was supplied by a network of relations and a stream of au pairs that trudged in and then promptly out of her home when they discovered the bright lights of London, too close to Leigh to resist for long. The girls (Ilana, Tia, Cesca, Vilette, Sofia, Anna and most recently Giselle, in the twenty-six months since I’d moved here) seemed like they were on a constant rotation from Europe to Leigh to London then back to Europe. Corinne coped with it all, remaining optimistic in the face of constant chaos and disruption. She was a good friend to have around in times of crisis.

So, first I told her about the doctor. She was concerned and then, when she detected hysteria in my voice, incredibly reassuring.

‘That’s what Doctor Cook is like,’ she said. ‘Why do you think he’s got such a massive patient list? Because he’s really good. Leaves no stone unturned. It’s probably routine.’ I noticed her pronounced Essex twang was softened by the drawn-out vowel sounds she used when she was calming Ewan. It worked on me too.

‘Do you think so?’ My voice sounded high and girlish compared to hers.

‘Of course! Sarah, remember back when we were talking about your school’s maypole dance being cancelled?’

‘Yes?’ I couldn’t see where this was going.

‘And you were banging on about what a litigious society we live in and doing your nut about health and safety?’

‘Oh yes.’ The incident had got under my skin for some reason. It had been a tradition at the school for as long as the place had stood but this year, my manager, McWhittard, or McBastard as we oh so wittily called him behind his back, had been appointed manager for Health and Safety. I don’t know who had made that decision and hoped that they regretted it now as McBastard had embraced his additional responsibilities with the zeal of a new convert. So far this year, several events had succumbed to his stringent application of risk assessment; the maypole dance being the latest victim. McBastard insisted we would need to sink a concrete base into the sports field in order to conform to new European safety standards. He’d also confided in John that he didn’t approve of the ‘pagan connotations’. Gerry the caretaker had started running a book on McBastard’s next reforms. I’d got £20 riding on the Halloween party being cancelled but hoped secretly I wouldn’t win.

Corinne coughed and continued. ‘Well, imagine if your McBastard went to Doctor Cook and he didn’t spot what was wrong with him. Do you think he’d sue?’

I nodded so vigorously I almost dropped the phone. ‘Oh he’d sue all right, and screw the NHS for all he could get.’

‘Right. Well, that’s why the good doctor has to cover everything. He can’t leave himself open for people like that to take advantage. Not that someone like you would, of course. But he doesn’t know you, does he? He’s making sure he’s doing the right thing. I really don’t think you should worry about it and he did tell you not to. Just forget it.’

Reassured, I said, ‘Do you think so?’

‘Yes, I do.’

‘OK. I’ll try not to think about it then. But there is another thing I wanted to talk to you about.’ I swapped the phone into my left hand so that I could inspect the skin where the burn had been.

‘What’s that?’

There was an irritation behind Corinne’s drawl that made me hesitate.

‘I had this dream, last night …’

A distant wail started somewhere in the depths of her house.

‘Hang on.’ The phone muffled. ‘Gi-selle? Oh bugger. I forgot: she’s gone to the Billet. Fancies one of the fishermen.’

I smiled. A couple of previous au pairs had fallen for Londoners and moved up to be with them. The Crooked Billet was a popular pub in the Old Town. ‘At least he’s local.’

‘Yeah, I suppose.’ Corinne sounded as flustered as she ever got. ‘Look, it’s Ewan. I’ll have to call you back.’

I hung up and went to replenish my glass.

In the kitchen it was quiet. The CD had finished playing and whilst we’d been drinking and talking darkness had crept in through the open French doors. I sat down at the table and lit a scented candle.

Something cracked on the window. A sting of adrenalin shot through me.

I put down my glass and crept towards the window. Despite the heat, by the door there was a pool of cool air just outside. Something little and white gleamed on the decking. I picked it up.

A cockleshell.

For a moment I was confused, then remembering Alfie’s room was right above, I wondered if he’d left it on his windowsill. Or perhaps a seagull had dropped it.

I turned it over in my hand. Curious. It was wet.

Crack. Another sound came from behind me. This time in the living room, softer than before. I spun around and stared into the gloom. Nothing moved.

My heart was hammering.

I wished for Josh’s reassuring presence but knowing he wasn’t there I made an effort to bring myself under control. ‘Don’t be silly,’ I whispered aloud. ‘It’s an old house with its own creaks and groans.’

I forced myself to walk to the centre of the room where the noise had come from. A gasp escaped me as I saw, there on the carpet, another shadowy shape. This was larger and darker. A pine cone.

The sound of my mobile ringing made me jump. When I answered it, Corinne’s gravelly voice brought me back to my senses. ‘Sorry, Sarah. Another nightmare. He’s fine now.’ Then, hearing my breathy pants, ‘You all right, chick?’

It was right on the tip of my tongue to tell her about my dream but in that instant I knew what she would say, and somehow right then, Corinne’s dismissive but sensible advice was the last thing I wanted to hear. She’d done enough for one night and she had more than a handful in Ewan.

My voice was scratchy and dry but I managed a squeak. ‘Yes, sorry. Hayfever.’

‘Quite bad this year I’ve heard. Rachel’s had it awful and she’s even had these injection things that are meant to clear it up for years, poor thing …’ And she was off and into the night, chatting about our mutual friends, oblivious to my silence.

When we’d said goodbye I went around the house and locked up carefully. I crept to my room and turned on the television, the radio and both of my night lights.

As I sank under the duvet and closed my eyes against the light, I couldn’t shift the feeling that I was waiting for something.

It would take another seven nights for me to find out what that was.

Chapter Three

Looking back, all the signs were there. Human beings have a tendency to forget what they can’t explain: the misplaced key, left on the sideboard but found in the lock; the lost treasured trinket, carefully tracked and then suddenly gone; the darkening shadow in the hot glare of day. But they’re alarm bells.

Would it have all turned out differently if I had paid heed? I think not. The chain of events that would carry me across seas, to foreign shores and through time, had already been set in motion.

But I didn’t know that then.

In fact, as I contemplated the past week from the end of my summer garden, things seemed so obvious and straightforward. To my mind they were almost bordering on the mundane. But then I had cosseted myself in the flower-boat, one of my favourite places to be: a hammock strung between an apple tree and the fence post, beside an ancient pink rose bush. Alfie christened it the flower-boat as I’d fashioned it from a faded tarpaulin with a swirl of daffodils and gerbera printed upon it. In its saggy hug, when the sun sank and the jasmine that wound itself around the fence scented the air, it was impossible to feel anxious. I had even fixed a shelf into the lower branches of the apple tree so that we could reach toys, drinks and magazines as we gently rocked. The scent of floribunda and ripening apple fruit, the faint gurgle of traffic and life that wafted along on the breeze, couldn’t help but soothe the nerves.

It must have been Alfie who had left the shell and the cone about the house; there were only two people who lived here, after all – me and him. And I hadn’t done it. It is the kind of thing that kids do. My attention had been drawn to them as the house creaked that darkened Friday night. The seasonal heat had surely disorientated a winged insect, which had flown into the window, hence the cracking sound. The groan of a floorboard, contracting as it cooled in the night air, had alerted me to the cone.

The burn was more of a puzzle. But I’m scatty at the best of times and in the rush to get dressed, pop Alfie to nursery and scoop up my lesson plans, it was quite possible that I’d simply imagined the scar, a residual phantasm created by the dramatic dream.

I’d tell the neurologist.

I took my anti-depressant, minus 10mg.

All too soon the week’s mundanities had me.

I don’t like using the term ‘roller coaster of a ride’. Whenever I see it on the back of books it makes my bottom tighten. So without using crappy marketing-speak, let me tell you the week that followed was so frenzied it was easy to forget about the cockleshell and pine cone incident.

St John’s was busy. It was the last week of lessons and the students weren’t interested in their work. Not that they had much at that point in the academic year. I was half inclined to let them do as they pleased, but the college executive herded us in to the Grand Hall at 8.30 a.m. Monday morning and instructed us that this was no time to let standards slip. According to the management, this week was the perfect time to introduce students to next year’s curriculum.

McBastard suggested that if we wanted to relax a bit we could carry out summative assessments in the form of quizzes. ‘Party on, dude,’ said John, in a rare moment of rebellion. The management made him stay behind.

They were like that at St John’s.

I’d come out of the music business, which doesn’t have the reputation of a caring profession, and thought that perhaps teaching might be a less stressful, more wholesome career. Ha ha ha.

On the Tuesday I sneaked Twister in to my Textual Analysis lesson. The kids were enjoying it until McBastard caught us and hauled me into his office. If that sort of thing continued, he growled at the floor, I could end up on the Sex Offenders Register.

I laughed.

He fixed his strange brown eyes on me. Ambers and reds swirled within them like fiery lava.

‘This is serious,’ he said. ‘You should be careful.’

I frowned and shifted on the stool where I was sitting in front of his desk. ‘What do you mean?’

McBastard leant back and clasped his bony hands in a prayer-like fashion.

Malevolence glittered beyond his volcanic eyes, anger preparing to erupt.

‘You need to keep your job.’ He stayed motionless, hard, like a statue.

I wasn’t absolutely sure what he was trying to say and told him so.

Finally he spat out, ‘A woman in your position.’

It took me off guard.

‘Yes? What exactly is that?’ My eyebrows had raised and I’d assumed an expression of confusion.

Thin white lips pushed themselves into an arrangement that almost resembled a smile. ‘A single mother, after all.’

Reading my puzzlement he seemed about to say more but stopped. ‘You’d better toddle along to your class.’ Then he dismissed me by spinning his chair round and staring out of the window.

Gawping at the back of his head, I was shocked into silence, as his meaning dawned.

It was true, I needed to earn money and I couldn’t afford to lose my job. But I didn’t need reminding that whether I stayed in it or not was largely up to him. The shit had used this opportunity to warn me: fall in line or fuck off.

I quivered at my impotence in the face of such barefaced blackmail but with great self-control I thanked him and ‘toddled’ back to my students.

The following day McBastard stalked me like a wolf. Thankfully there wasn’t much I could screw up: end of year shows, graduation ceremonies, leaving lunches and then on Thursday, a trip to Wimbledon.

On Friday the school was shut to students and staff were subjected to what the management term a Development Day, but what we call Degenerate Day on account of the stupefaction factor – the programme comprised policy talks and lectures.

I took my place at the back of the staff room between John and Sue, who was pregnant and perpetually pissed off that she couldn’t smoke or drink.

‘Do we know how long this will be?’ I squeezed into the cramped makeshift seating.

John grimaced. ‘They confiscated my shoelaces on the way in.’

‘I can’t fucking believe it,’ said Sue, sucking on a biro. ‘There’s so much else I could be doing. Don’t they realize we have all this end of year admin to tie up?’

‘Oh, they realize all right,’ said John.

One of the management posse had positioned himself right in front of the coffee machine, cutting off our lifeline to the one thing that might keep us conscious. He clapped his hands to get our attention.

Not a good start.

His name was Harvey. Apparently he’d been doing this for three years now and had got a lot of positive feedback.

‘Inadequate,’ John whispered. ‘Needs to self-reinforce.’

Harvey launched into a ‘discussion’ of why students should be called customers. He got some audience interaction going with a show of hands – who was for it? McBastard. Who was against it? The plebs voted unanimously. Then he did this sickly smile and said: ‘Well, I’m afraid these days anyone with that way of thinking is completely out of sync with new models of educational theory. It may have been OK thirty years ago but now the terminology is inconsistent with new approaches to learning and changes in funding.’

Harvey continued to bellow: in order to survive in the new market place, every single one of us had to commit ourselves to ‘rethink, reset and reframe’. Just then a ball of paper arced over from the back and got Harvey right on the chin.

McBastard leapt to his feet. ‘Who did that? Come on now!’

Everyone looked at the floor.

Harvey ploughed on.

The room calmed down and we started settling in for a nap, when he repeated his point that we ‘needed to change or become history’.

This was the last straw for the History ‘facilitator’, a quiet guy called Edwin with hair like a toilet brush. He leapt to his feet and shrieked something sarcastic about that not being so terrible as we could learn from history, if ‘learn’ was still a permissible verb, given current educational thinking.

If he’d been more popular there might have been a revolt at this point, but Edwin was a bit of a dick so no one joined in.

Harvey looked embarrassed and back-pedalled to qualify ‘history’.

John bobbed his head in Edwin’s direction, mouthed ‘wanker’ and supplied a pertinent hand gesture.

‘Good point,’ I sighed. ‘I bet he’s added at least another five minutes on.’

He had.

Time slowed.

John fell asleep. Sue’s biro leaked over her chin and onto her polo neck.

I watched McBastard out of the corner of my eye.

For two hours and seven minutes he didn’t once take those fireball eyes off me.

After lunch things worsened. But at 4.30 there was a serious breach of health and safety when the entire staff (plebs) of the Humanities and Arts Department stampeded to the Red Lion.

There was no way I was missing out on a much needed dose of medicine. Luckily I’d got the bus into work this morning so didn’t have to worry about the car.

A quick call to Corinne resulted in Giselle agreeing to pick up Alfie and babysit. Thank God for the empathy of fellow mum friends. Adversity unites.

My pass for the night acquired, I joined the last of the stragglers beating a path to the local.

John was in fine form. The day had supplied him with plenty of ammunition. Especially Harvey’s utterly absurd suggestion that, to help us memorize what we learnt from the session, we could make up our own raps. A natural mime with a wicked sense of humour, his impression of Harvey’s twitches, stammers and idiosyncrasies was cruel, excruciating and magnificently funny.

A charismatic teacher with a background in media law, the students, I mean, customers, loved John. You could understand why when you saw him in this context, holding court; engrossed and animated. His curly brown hair tumbled down past his ears, lending him a naturally cheeky quality that was muted somewhat by serious blue eyes, a clean-shaven face and an insistence on wearing a suit. God knows why he accepted a fifth of what he could be earning, working harder than he would in a small law firm. I liked his intelligence and respected his mind. He’d almost become a good friend.

Later, as the conversation waterfalled into pockets of twos and threes, we found ourselves together.

‘You all right then, Ms Grey?’

I paused and took a slug from my glass. ‘D’you know what? It’s not been the greatest of weeks.’

‘It’s always like this,’ he said. ‘End of term. Shit to do. Shit to teach.’

It wasn’t work, I told him, and was about to relay my medical experience when I remembered that he was a colleague and much as I liked him, there was the possibility that, well-oiled and talkative, he might mention it to one of HR. That might kick-start a sequence of events that I couldn’t afford right now. Not with McBastard on the prowl.

‘What is it then?’ He looked concerned and I felt a bit daft looking at him with my mouth open, so I told him about the cockleshell instead.

‘Jesus,’ he said. ‘You sound like my sister. Marie’s nuts, obsessed with crystals and weirdies and things that go bump in the night. She’s on her own too. Out in California now. Do you know what I reckon?’ He slurred the last part of the question so I had to ask him to repeat it.

‘That,’ he wagged an unsteady finger at me, ‘women on their own tend to imagine stuff. I’m not being sexist here but when you’re living with someone, you talk to them, you know, you share stuff. You talk things through. You don’t let things run away with you. Do you know what I mean?’

As unwilling as I was to let the poke go unchallenged I did know exactly what he was getting at. Especially after that night. But I didn’t think it was a gender thing so instead I said, ‘Are you inferring that us independent ladies become hysterical without a rational male mind, Doctor Freud?’

‘Yes of course, dear,’ he said, and made a big thing of patting my hand. Then Nancy, one of the administrators, swung our way. ‘What are you two talking about?’ Her beady eyes strayed over John.

‘Nothing,’ we chimed together.

She looked at us sceptically but didn’t move. ‘Whatever.’ Her voice always sounded thin and discordant.

John started doing his impressions thing again and having heard it all once, I got up and staggered over to Sue. The subject there was giving up fags so when, inevitably, everyone got up to go for a smoke, I went too.

Outside Edwin was hailing a cab for Leigh, and realizing I was more wrecked than anticipated and that it was only half ten, I joined him. Twenty minutes later I’d paid Giselle and had seen her off in a cab of her own.

Alfie was snoring lightly so I jumped into the shower, ran the water lukewarm and lathered one of my favourite exotic gels over my sticky body. It felt good. In fact, I felt good. Considering the day I’d had, this was something of a miracle.

I closed my eyes and let my mind drift. My hands took the lather and soaped my breasts. I turned the hot tap up and killed the cold, soaked my hair in the shower spray and let the shampoo’s foam glide over my midriff and drip down my thighs.

The hot water ran out. I squealed as a prickly blast of cold hit my belly and reached out to turn it off, cursing the immersion heater. I stepped out of the cubicle and grabbed the nearest towel.

Wrapping it around my body, I felt the weight of the last week enveloping me. I dried myself then cleared the steam from the mirror to apply some face serum.

That’s when I saw it.

As I looked in the mirror I saw my face, but hovering over it there was another – the same shape, but with a firmer chin. Locks of hair blocked out my own wet brown wisps – hers was a darker shade and thicker. But it was the eyes that held me – vivid green, bright, almond shaped – that fixed onto mine. Compelling me to hold her gaze.

My mouth, reflected in the mirror, froze open in shock, and morphed into two thin pink closed lips.

The vision held, then blurred.

I blinked and it had gone.

The air was steaming up the mirror once more. I steadied my breath and rubbed the condensation away. My reflection stared back: pale, crumpled and very, very tired.

I was still tipsy. I had to get a grip; my imagination was running away with itself, playing tricks on me.

‘Pull yourself together,’ I instructed my reflection. ‘You just need a good night’s sleep.’ I took my own advice and pushed the fear to the very back of my mind.

Flinging on my pyjamas I shuffled out of the bathroom as quickly as my tired legs could manage, dragged my body to my fluffy bed and pulled my duvet tight around me.

It wouldn’t register consciously then, but just before I sank into oblivion, I saw a small cloud of my breath.

Despite the warmth outside, my bedroom was as cold as a crypt.

Chapter Four

When I woke I was moody and morose. Though I tried to perk myself up when I roused Alfie, I never really got rid of that shirty, melancholy the whole weekend. In fact it got worse.

I had a slight reprieve late Saturday morning (less of the melancholy, more of the shirtiness) when my sister, Lottie, and nephew, Thomas, turned up for a picnic at Leigh beach. Thomas was eight months older than Alfie and the boys got on very well together.

The sun was nearing its noon zenith when they arrived. My hangover had slowed me so I was still half dressed. Lottie made it clear that she wanted to spend no time inside. A true sun-worshipper, she insisted we packed a picnic lunch and got down to the beach as soon as possible. I tried not to sulk but my older sister’s assumed authority and unassailable competence always brought out the child in me. Lottie had always been more organized, more academic and wittier than anyone else. Leaving college with a first-class degree in English, and with an outstanding final term as an award-winning editor of the college mag, she dashed everyone’s expectations by turning her back on a promising career in journalism and established her own theatre company, which she ran for several years before a BBC head-hunter netted her. She gave up working for the BBC when she was pregnant with Thomas and now worked as a freelance consultant. In her spare time she was writing a trilogy of children’s books for a US publisher.