The Drowning Pool

We all went ‘Ah!’ and nodded.

I said that I had looked at a flat there.

‘What was it like?’ asked Sharon. ‘Never been inside one of them.’

I thought back. God, it had been horrible. Not the interior or the layout but the atmosphere. There was a sharp sense of misery lurking in the corners. It had hit me as soon as I’d walked through the door. But I was still raw then. I reckoned it was just the similarity to my flat back in London and the emotional wreckage that had surrounded me there. But I simply said, ‘It was too small. Smart enough, good finish.’

Anyway, Corinne was off again so we returned to her pretty face flickering in the firelight. ‘Before the flats there was a supermarket on the site. My friend’s mum used to work there. She said the shelves were wonky. You used to put the tins on one end and they’d slide down the other and onto the floor. Then one day she went to work and it had gone. The whole place had slid into the pond.’

Martha shifted her weight from the left buttock to the right. ‘So, is that why they call it Doom Pond?’

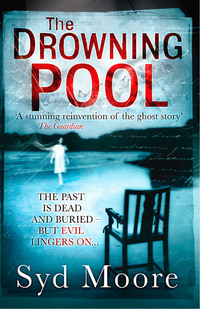

Corinne shook her head. ‘Nah. It used to be referred to locally as the Drowning Pool.’

A flurry of unseen wings took off somewhere in the darkness.

‘Really?’ Goose bumps appeared across the bare flesh of my arms. The name sent a shudder right through me. ‘Why the Drowning Pool? What else happened there, apart from dunking scolds? Blimey, did they actually drown people?’

Corinne shrugged. ‘I guess it must have had something to do with local witches.’

‘Local witches?’ The casual comment intrigued me. ‘You say that as if they were commonplace.’

Corinne’s eyes flitted across Martha and Sharon then back to me. ‘Sarah, this part of the country is riddled with folklore. I know you wouldn’t think it now but Essex was once known as “Witch County”. The village of Canewdon is meant to be the most haunted place in England. And there was the wise-man and sorcerer Cunning Murrell in Hadleigh.’

Sharon straightened herself. ‘So did he get done then? For being a witch?’

‘No,’ said Corinne. ‘He was actually quite well-respected by the community, although he obviously still had a fearsome reputation.’

Martha leant forward and threw a couple of twigs on the fire. ‘So witches got subjected to all sorts of ill treatment yet Mr Murrell’s skills were, er, more appreciated?’

Corinne opened her mouth to reply but Sharon was in there immediately. ‘Because, my dear Martha, he was in possession of a cock.’

I sniggered. Martha laughed and poked the fire. ‘You’re about right there.’

‘So,’ I said, steering the conversation back to the pond topic. ‘Why the “Drowning Pool”? You said because of the witches. What have they got to do with the pond?’

‘Oh right,’ Corinne nodded and took a sip of her wine. You could see she was enjoying the limelight. ‘They used to “swim” them there: the witches would get tied up, sometimes right thumb to left toe, other times they were bound to a chair, then they would be thrown in the pond. If they sank and drowned they were innocent, if they floated, they were a witch, and would be dragged off to the gallows to be hanged.’

Martha said, ‘Talk about a no-win situation. Poor women.’

I sent up a silent prayer of thanks that I hadn’t bought that flat.

‘So,’ said Corinne, anxious to go easy on the tragedy and high on spooky. ‘That’s why locals say it was haunted. By the restless souls of the witches and innocents drowned there.’

‘And Sarah Grey,’ said Sharon sadly.

I went, ‘Wooo.’

But nobody laughed this time.

Martha started talking about a ghost in the cemetery and we all crowded in. The stories picked up and whirled on and on into the midnight hour, with wine flowing, the girls howling and the fire roaring.

I now understand, as I’m writing it down, that what we were doing, without realizing it, was creating some kind of séance. We stirred things up, opening a rift. Things got channelled down.

But that’s all come with the benefit of hindsight. If only I’d had a clue at the time. Things were, of course, happening but nothing really registered until the girl on fire.

But I need a drink before I start that one.

Chapter Two

That June was one of the hottest we’d had for years, which, on the plus side, meant that Alfie and I were able to spend a good deal of time down in the Old Town, a cobbled strip of nostalgia severed from the rest of the town by the Shoebury to Fenchurch Street train line. We liked it down there, crabbing, paddling and building sandcastles on the beach. Although Alfie was too young to miss his father, back then Josh’s absence still stung like a fresh wound, so I tended to overcompensate with painstakingly organized ‘constructed play’ and serious quality time. But it was fun. Alfie was now four, a lovely boy with his dad’s well-humoured outlook and a steady stream of gobbledegook that made me smile even on bad days.

On the down side, the heat-frayed tempers amongst students and staff at the private school where I taught Music and Media Studies. A few miles into the hinterland, surrounded by acres of carefully landscaped gardens, St John’s had been one of the county’s few remaining stately homes. It was converted from a family residence into a hospital during the First World War. In 1947 it became a private secondary school. Since then its buildings had encroached onto the lawns in a steady but haphazard and entirely unsympathetic manner. The block in which I worked was a 1980s concrete square that, rather surprisingly, managed to churn out excellent academic results and was in the process of expanding over the chrysanthemum gardens with another inappropriate modern glass structure.

Despite the new build however, the recession was eating into the public consciousness and the economy’s jaws were contracting. As a consequence our day students were being pulled out left, right and centre.

My boss was Andrew McWhittard. A forty-year-old unmarried, bitter Scot with a malevolent mouth. Tall and lean with a smother of thick black hair, he caused quite a stir amongst the female support staff when he arrived to head up the team. The honeymoon lasted two weeks, by which point he had revealed himself to be an HR robot – built without a humour chip and programmed only to repeat St John’s corporate policy. Personally, I found him arrogant in the extreme. When we were first introduced he gave me this look like he couldn’t believe someone with my accent could possibly work in a private school.

You live and learn.

McWhittard was a bully at the best of times and of late had started reminding us that pupils meant jobs, and the loss of them did not bode well for our employment prospects. He loved the fear that generated amongst us, you could tell.

A couple of administrators had gone on maternity leave and had not been replaced. The unspoken suggestion was that we absorb the admin ourselves. I only taught three days a week but my paperwork increased substantially and what with the marking, exams, reports, open days and parents’ evenings, June is the cruellest month of all.

Plus I had this other thing; one of my eyelids had started to droop. It wasn’t immediately obvious to anyone else and, at first, even I assumed it was down to tiredness. But after a week without wine and five nights of unbroken sleep, it was still there, so I booked an appointment with the doctor. The receptionist told me the earliest they could see me was Friday morning before school so I took that slot.

So you see, I had a lot on my mind. Which is why it took me a while to tune into Alfie’s strange mutterings.

Like I said, he was a born chatterbox – even before he formed words he’d sit in the living room with his Action men, soldiers, firemen and teddies and act out stories, giving them different voices and roles. The ground floor of our 1930s villa was open plan with large French doors leading out onto the garden. The design meant I could potter around with the vacuum cleaner or do the washing up with one ear on the radio and the other on my son. Though recently Alfie had taken to setting his toys out in the garden instead of staying indoors.

It was the Monday before my visit to the doctor’s that it first occurred to me to question why. My initial thought was that Alfie wanted to enjoy the sunshine. But then that was such an adult custom: I remembered the bleaching hot summer Saturdays of my childhood, sat on the sofa with my sister, Charlotte, or Lottie as she preferred, watching children’s TV, oblivious to the gloom of the room. How many times had Mum flung back the curtains and berated us for staying in on such a beautiful day? How many times had we shrugged and carried on regardless?

All kids love playing outside but they don’t make the connection when the sunshine appears. It takes many more years to wise up to the fickle nature of our very British weather. You certainly don’t get it when you’re four.

So, I peeled off my Marigolds and went to stand by the French doors. Alfie was sitting on the grass by our old iron garden furniture. He had lined up his puppets to face the chairs, and was engrossed in ‘doing a show’. It was a few minutes before he became aware of my presence, then, when he did, I was formally instructed to take a seat and join the audience.

There were four chairs, two either side of the table. I fetched my mug of coffee and was about to sit on the chair to the left when he shouted, ‘No, no, no. Mummy, no!’

It’s not unusual for kids to fuss over little things, they all have their own idiosyncrasies, so I let Alfie grab my skirt and guide me to the farther chair.

‘Sorry, Alfie.’ I grinned and leant over to put my mug on the table, but he was up again.

‘No, Mummy. Not there!’ A little toss of his golden locks told me he was cross now. He frowned, took my free hand and led me to the other side of the table. ‘You sit there.’

‘You sure, sir?’ I said gravely.

‘Not that one,’ he said, indicating the chair which I had so rudely stretched across. ‘The burning girl is there.’

He rubbed his nose and went back to the puppets.

‘Sorry.’ I laughed, indulging him. I had wondered if he’d develop any imaginary friends and secretly had hoped that he would. Lottie once befriended an imaginary giant called Hoggy who ate cars and ended up emigrating to Australia. As a kid I was absolutely enthralled by her Hoggy stories. Later they proved hugely amusing to an array of boyfriends.

‘What’s her name?’ I asked Alfie. He was concentrating hard on pulling Mr Punch over his right hand and ignored me.

I reached over and tapped playfully on his head. ‘Hello? Hello? Is there anyone there?’

Alfie wriggled away.

‘What’s your friend’s name, Alfie?’

He turned his back on the irritation. ‘Dunno.’

I was getting nowhere so contented myself with observing him. He was funny and sweet and growing up so quickly. It was in these quiet moments that I missed Josh. The reminder that there was no one else to share my fond smile was painful.

Widowhood is a lonely place.

After a few more tries Alfie mastered the puppet and spun round. ‘That’s the way to do it!’ he squeaked in a pretty good imitation. Then, glancing at the empty chair, his face puffed out and his shoulders fell. He snatched the puppet off his hand and threw it on the floor. ‘Look what you done!’ Alfie jabbed his podgy index finger at the iron seat. ‘You made her go! Mummy!’

He looked so cute when he was angry, with his fluffy blond hair and dimples, it was all I could do not to sweep him up in my arms and kiss him all over his beautiful scowling face. Instead I stuck out my bottom lip and apologized profusely, promising a special chocolate ice cream by way of recompense. This seemed to do the trick and I thought no more of the incident till later on Thursday night.

I’d cleared away the remnants of our pizza and was finishing up the last glass of a mellow rioja when I turned my attention to coaxing Alfie upstairs. He was resisting going to bed, unable to see the sense in sleeping when the sun was still up. No amount of explaining could persuade him that it was, in fact, bedtime.

So far he’d tried all the usual techniques: the protestations (‘Not fair’), the distraction method (‘Do robots go to heaven?’), the bare-faced lying (‘But it’s my birthday’) and the outright imperative (‘Story first!’). But he was pale and tired so brute force was necessary.

He was by the French doors, and as I lifted him, he stuck out his hand and caught one of the handles. As I tried to step away he hung on to them, preventing me from going any further.

‘No, Mummy. Not yet. Girl’s sick. See.’ With his free hand he pointed into the garden. It was empty but for a spiral of mosquitoes above the rusting barbecue.

I was getting annoyed now – it had been a hard day at school. My neck hurt and I wanted to slip into the bath and soothe my aching muscles. ‘There’s no one there, honey. Come on, it really is time for bed.’

‘But the girl.’ His grip tightened. ‘The girl is on fire.’

There was something plaintive in his voice and when I looked into his face, two little creases stitched across his forehead. I prised his fingers off the handle one by one and opened the doors. ‘Look.’

In the garden a faint smell of wood smoke lingered and I wondered briefly if it had been the whiff of the neighbour’s barbecue that had sparked his fantasy. ‘There’s no one out here, Alf.’

He wasn’t convinced. ‘Will you call the fire brigade, Mummy?’

The penny dropped. All kids love fire engines and Alfie was no exception.

‘Oh yes, of course, darling. I’ll call them right after you’ve had your bath.’

He shook his head. ‘No, now.’

‘OK. I’ll call them now. Then will you come upstairs?’

He put his fingers on my chin and looked into my eyes. I poked my tongue out. He smiled. ‘Yes. But now.’

After a quick call to ‘Fireman Sam’ (no one) at the Leigh fire station, he submitted and within an hour was tucked up in bed and dozing peacefully, leaving me exhausted. In fact an intense weariness came over me as I looked in the mirror and stripped my face of make-up and suddenly it was all I could manage to crawl into bed with my book.

I remember it well. I remember everything about that evening – the dappled sunshine that caught the shadows of the eucalyptus in the front garden, the aroma of lavender oil on my pillow, the fresh linen smell of my sheets and the pale amber glow in the room.

It was the night that I had my first dream.

It opened in the usual way that dreams do, with familiar places and people: Alfie and me on the sand. Corinne, Ewan and Jack were there too. And John, a rare breed of colleague and friend. We were at a picnic or something. Then I was on Strand Wharf, just along from the beach, my feet caked in clay the colour of charcoal. There was a scream and a young girl ran from one of the fishermen’s cottages. She was making a strange noise, like the hungry cry of a seagull or the wail of a dying cat. When I looked at her again, flames were leaping up her pinafore. They licked onto her ringletted tresses and about her face. Filled with horror, I ran to her. I had a canvas bag in my hand, which I used to beat at the flames. But the fire wouldn’t go out. It got worse, blustering up against me, enveloping the girl. Searing pain crept over my fingers but her dreadful cries forced me on quicker.

Then abruptly I was awake, covered in sweat, panting in the lemon sunlight that seeped through the blinds.

It took me a few seconds to work out where I was. I could have sworn the smell of burnt flesh lingered in my nostrils.

The nightmare had unsettled me but you didn’t have to be a genius to work out what had inspired it.

I sank back into my pillow and steadied my breathing.

The clock showed that it was early morning, but the nightmare had been vivid and I realized that it would soon be time to get up. I wouldn’t be able to go back to sleep anyway. Having missed my bath the previous night, I ran a tub full of water, laced it with lavender salts and gratefully sank in.

Fifteen minutes into the soak, as I reached for the soap, something caught my attention on the fleshy mound of skin beneath my right thumb and above my wrist: a crescent-shaped welt.

My fingertips traced it lightly. It was raw. A burn.

I paused, disorientated. I couldn’t remember hurting myself. But then again I had polished off that bottle of red. Bad Sarah.

Relinquishing the warmth of the water, I stepped out of the tub and rummaged under the sink for some antiseptic ointment.

A squirt of Savlon softened the pain.

Alfie toddled into the bathroom and had a wee as I was bandaging it.

‘Watcha done?’ He had an acute interest in injuries.

‘Mummy hurt her hand last night.’

He closed the toilet seat with a loud crack. ‘How?’

‘I think I burnt it while I was cooking the pizzas.’

Alfie stuck the tips of his fingers under the cold tap. ‘Like the girl in the garden.’

That stopped me in my tracks. Something bitter in the pit of my stomach uncoiled. ‘Now listen, Alf, I want you to stop talking about that. It’s not very nice, you know.’ I shivered.

He looked at me with wide eyes. ‘But …’

I held up a finger. ‘No buts. Now come on. Let’s go and have a nice big breakfast. Then I’ve got to get you to nursery early – I’ve got to go to see the doctor today.’

Alfie reached out and stroked my bandage. ‘About your burn?’

‘No,’ I hesitated. ‘Yes, about Mummy’s burn.’

‘Poor Mummy,’ he said, and kissed me. He could be such a darling at times.

Doctor Cook’s surgery, situated in the right wing of his grand Georgian home, lacked the cleanliness of most GP’s but his reputation was one of kindness and benevolence. Plus he’d come with Corinne’s recommendation, having been her family’s doctor since time began. So I’d picked him over the more contemporary surgery up the road.

The family from which the doctor was descended was one of the oldest in Leigh, well-respected and valued, often spoken of in hushed tones: back in the day when the place was significant enough to have its own mayor quite a few of the family passed through that role apparently elevating their reputation and wealth. The family seat itself was now something of a tourist spot, shrouded by lines of cedar trees and set back in sprawling but well-kept gardens. Locals were able to enter it and marvel at the baroque interiors and lush furnishings but only as patients.

In fact, Doctor Cook was a bit of a local celebrity – not only an excellent GP and an active and well-respected councillor whose name featured frequently in many of the local papers. There was also a tinge of gossip linked to his past: an absent wife or some domestic scandal. I couldn’t remember which and was very curious to meet him. Thus far my experience had been limited to his junior partner, as the senior doctor was booked up for weeks in advance, so I was somewhat surprised to be ushered into the head honcho’s consulting room.

Cook turned out to be older than I had imagined, in his late sixties. He had an old-school bedside manner and a taste for natty bow ties. However, he exuded gentleness and I was glad I’d got him for the appointment. I had assumed I’d be in and out like a shot with some reassuring platitudes about the thirty-something ageing process and instructions to come back if the droopy lid got worse. But Doctor Cook was thorough. After an extensive inspection of both eyes and ears, he had me up on the couch, examining my arms and legs and listening to my chest.

After I’d got dressed and sat down in the leather chair by his desk, he asked, ‘So Ms Grey, have you noticed any changes in your character lately?’

It totally threw me.

‘I, um, well …’ Blood rushed to my face. ‘Not really. I’m a bit stressed at work, but …’

The doctor took off his spectacles and relaxed into his chair. ‘And what is that, my dear?’ His voice was rich and low with a hint of a hard upper-class accent.

‘I teach. At St John’s.’

Under bushy grey eyebrows his eyes glittered, very blue and piercing. I had the strangest feeling that he was looking right into me. ‘And that’s,’ he paused to find the right word, ‘manageable?’

‘Well, yes. My boss is a bit of a nightmare but, you know, that’s education for you.’

‘Is it?’ he said, rhetorically, and picked up my bulging brown wad of medical notes. ‘I see here that you’ve been on anti-depressants for a while.’

I gulped hard as if I’d been caught out. ‘That’s right. I lost my husband about three years ago.’ Two years, ten months and four days, to be precise.

Usually I held back on details like this. It had a peculiar effect on people, often stopping conversations. Women floundered, not knowing whether to ask for more details, worried that they may upset me or appear morbid. Men coloured, the more predator-like practically licked their lips and stepped closer. A few people physically recoiled when I told them, as if my status was contagious. Once, the thought of telling them that Josh had run off did cross my mind. But that was such a disservice to his memory I could never get the words out.

‘You’re a widow?’

‘Yes.’ I held his gaze.

‘I’m sorry to hear that. Children?’

An image of Alfie toddling into his nursery flew into my mind. ‘One, a boy. He’s four.’

‘Mm.’ Doctor Cook appeared to mull it over. He nodded. ‘Difficult. Are you coping?’

I kept my voice steady. ‘I have family locally who help out a great deal and good friends. Sorry, Doctor, but is this relevant?’

He pushed his chair back and faced me. ‘Well, my dear. In a way. I’d like you to consider coming off the tablets. Do you think you could?’ His eyebrows twitched into his forehead.

This was a surprising turn of events.

My feet hadn’t touched the ground since Josh’s accident. Then there had been so much to organize with the move back to Essex, finding a house in Leigh, starting the teaching job, sorting out a nursery. I’d started taking the pills when my body had been on autopilot and my head became frazzled with grief. Things were calmer now, it was true.

‘I don’t know. Why?’

‘Well, it might help us get a clearer picture.’

I cleared my throat. ‘A clearer picture of what?’

Cook leant towards me and assumed a kindly smile as he spoke. ‘I’d like to refer you to a neurologist. It’s nothing to worry about.’

I laughed, shocked. ‘In my book a neurologist is something to worry about.’

‘Yes, I quite see. Well, you’re on two tablets a day. Stop taking the 10mg. I think the 20mg tablet alone will work just as well.’ He tapped his desk. ‘It’s probably nothing, but I’m not sure that your eyelid has drooped as you’ve suggested.’

A small rush of heat spread over my palms. ‘Really? What is it?’

‘I’m not too sure, and that’s why I’d like to refer you. You have a weakness in your left side and I’m wondering if, perhaps, it’s your left eye that has swollen rather than the right lid that has drooped. I’d like to check, that’s all.’

‘Check? What would you be looking for?’

Cook looked away to his computer and jabbed at a couple of keys. ‘It could be that there is something behind the eyeball that is pressing against it and pushing it out. I don’t know.’

A wave of sweat broke out above my top lip. ‘A tumour?’ I blenched.

He continued to talk to his computer screen. ‘Let’s not leap to conclusions. This is why we have specialists and dotty old GPs like me aren’t allowed to make such diagnoses.’ He pushed his chair back and swung it to face me. ‘But it would be helpful if you came off the tablets so that we might be able to monitor your progress, as it were, chemical free. Reduce your dose by 10mg please.’

Suddenly I wanted to get out of there as quickly as possible.

I got to my feet shakily and held out my hand. ‘Thank you, Doctor. I shall. I guess I’ll be hearing from you.’