The Building of England: How the History of England Has Shaped Our Buildings

It was the location of bridges that determined the course of roads and stimulated their growth. During the 13th century there was a change from the idea of a road that simply went to the local market to the idea of a network serving the whole kingdom. This was stimulated by increasing trade, new ports and the economic activities of castles, cathedrals and monasteries. However, most importantly, towns could not grow without bridges and roads. Horse transport and a road and bridge network supported the rapid growth of towns such as London and Norwich that needed vast quantities of food, drink and firewood to survive. As a rough guide, a town of 3,000 people would need the produce of ten villages or over three square miles to support it, and all this had to be brought to town every day.17 Finally, the growth of an effective road network made it easier to transport building materials. The reliance on cheap but slow water transport decreased as faster horse-drawn wagons took over as the principal means of moving material round the countryside.18

Fig. 73 The medieval Exe Bridge, Exeter, Cornwall, built in 1200 through the efforts of Nicholas Gervaise, a wealthy merchant who was four times mayor of the city. Like many medieval bridges, it was endowed with property to provide an income for its upkeep.

Fig. 74 Thomas Hearne, view of Durham from the northeast c.1783. Elvet Bridge was rebuilt and extended in 1228 and incorporated St James’s and St Andrew’s Chapels, one at each end. In the background is the tower of the cathedral and, on a mound, the Castle Keep.

The Countryside

The Norman invaders came to exploit the English countryside. While they did not introduce a new system of social obligation on the population (Saxon lords had received all sorts of service from their dependants), the Conquest did result in the tightening and redefinition of the bonds of lordship. Norman landlords of the first generation were interested in labour obligations from their tenants, but later generations were more interested in cash from rents and fees, made possible by the fact that many tenants were generating a healthy cash surplus from agriculture by 1100. Villages were occupied by what we call peasants. The term is unfortunate as it gives the impression of poverty-stricken and down-trodden illiterates eking out a living from the soil. Villagers, who made up 80 per cent of the population, were in fact smallholders farming anything between 5 and 40 acres. Half held their land in villeinage; that is to say they owed their landlord payment, labour services and required permission to marry. The rest were freemen, who often had smaller landholdings. Villeins and freemen alike cooperated in the common-field system, where it existed (p. 54), but were also engaged in market activities: buying, selling and making money. By the 1180s the economic stability of the richer peasants started having an impact on the places in which they lived. This impact varied hugely across the country and even between adjacent villages. Dwellings were normally set in a banked or hedged toft of about a quarter acre within this (fig. 26). In some parts of the country – particularly the south-west – a single building or long house contained space at one end for people and at the other for animals. This arrangement was becoming less common by the 13th century; by then most tofts in the midlands and the south-east had a principal cottage grouped with a barn or granary and sometimes a byre. Richer peasants might also have a separate kitchen, a freestanding bake-house and even a dovecot or cart-house.

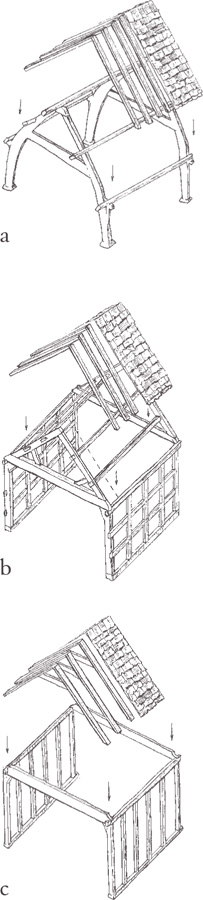

The crucial development in the period between about 1180 and 1320 was the introduction of various types of foundation, either for the full length of a building or just for its principal posts. The abandonment of earth-fast building (posts sunk in the ground) over most of England opened up the possibility for a variety of superstructures that in some parts of the country saw stone walls up to the eaves but more commonly saw a variety of timber structures resting on low or buried stone foundations. In the midlands, the west and north, most of these were crucks. A cruck is essentially an A-shaped truss made of large, slightly curving, timbers. A number of these could be erected on a timber base (or sole) plate and then be joined together at the top (ridge) and along their sloping side with beams called purlins (fig. 75a).

Fig. 75 As with all issues to do with medieval construction, techniques were highly regionalised and are resistant to easy categorisation. Yet a) cruck; b) box frame and c) post and truss construction are the most common categories found in the Middle Ages in England.

Alternatively, walls could be constructed with a box frame. Simple upright beams were jointed into a sole plate and capped by a top plate on which the roof trusses rested – this method was more common in the east and south (fig. 75c). A more sophisticated variation of this was the post-and-truss construction, essentially a timber-framed grid upon which the roof trusses rested, found in the west and south (fig. 75b). In all these cases the gaps were filled with wattle and daub – to make walls impervious to the elements – and the roof covered with thatch. Windows were small, glassless and furnished with shutters. Chimney stacks were rare, and fires would be lit in grates or boxes on the beaten-earth floors.

Most of these constructional systems resulted in framed units of about 15ft, making most houses either 30ft or 45ft by 15ft wide. So although peasant houses were dark and smoky, they were not smaller than workers’ housing in Victorian cities.19 They were also more private than might be imagined. Although the whole basis of village life was communal, especially where common-field systems predominated, the tofts – with their hedges and banks, which often rose to head height – and cottages with stout, locked doors, gave peasant families individuality and privacy. At Steventon, Berkshire, there are a number of cruck-built cottages of about 1270 to 1280 associated with a medieval causeway, but surviving peasant houses of this date are rare and most of our knowledge comes from archaeology.20

These cottages could not have been built by unskilled labour. It was necessary to employ a carpenter and have access to properly cut timber showing that by the 13th century there were thousands of carpenters working in villages as well as for the aristocracy, Crown and the Church. Nor did a house come cheap. It is likely that a straightforward cottage would have cost a peasant a year’s income, a sum that was probably borrowed and paid off like a modern mortgage.21

Fig. 76 The Psalter of which this is a page was commissioned by Geoffrey Luttrell, lord of the manor at Irnham in Lincolnshire in 1320–40. Uniquely, it shows scenes of everyday rural life, including this image of a typical 14th-century water mill. (from The Luttrell Psalter, c.1325–35, British Library. Shelfmark: Add. 42130, f.181)

Fig. 77 An early 14th century stone frieze from the infirmary hall at Rievaulx Abbey, Yorkshire. A contemporary windmill is shown with steps up to the door and a pivot for the whole building to move to catch the wind.

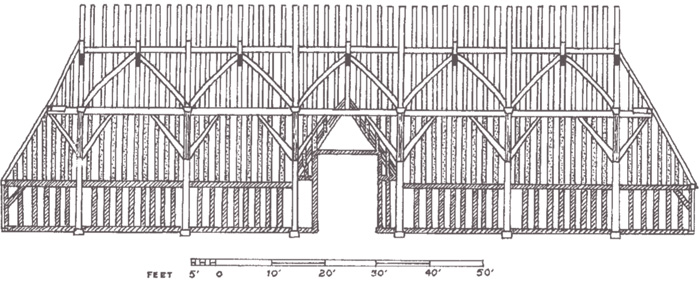

Fig. 78 Temple Cressing, Essex: a longitudinal section of the wheat barn of the 1290s. The barn is remarkably unaltered, and would have originally had wooden boarded walls.

The aristocracy gained about 60 per cent of their income from rents and fees but they were much more interested in agriculture than their continental counterparts; between 1184 and 1214 almost all took their demesne land into direct management. This they did with some success, refining crop rotation and exploiting existing sources of income more efficiently. One of the most important of these was milling, which, as we have seen, was very profitable. After 1100 landlords were busy building new mills and refurbishing old ones, doubling their number to perhaps 12,000 by 1300. In this there was one really important invention: the windmill. It is likely that the first one was built in East Anglia not long before 1185, but they took some time to perfect and construction only boomed in the east in the 1240s, followed by other parts of the country where fast-running water was scarce. A new windmill cost about £10 but they tended to have greater repair costs than watermills, which were cheaper to run though expensive to build. The water engineering alone could cost £15 or more. Watermills were of the type shown in the Luttrell Psalter (fig. 76); the mill building was like any normal timber-framed building and had a thatched roof. The windmill was much more specialised as it had to turn and face the wind. This meant that it had to pivot on a central mast, which had to be sturdy enough to resist the huge stresses of wind drag (fig. 77).22

Technological advances in milling were matched by advances in the quality and construction of other agricultural buildings. Barns were pre-eminent in the farmyard, crucial for the safe and dry storage of crops. At Temple Cressing, Essex, are two barns that were once part of the large estate of the Knights Templar. The earlier is the barley barn, erected in the 1230s; the wheat barn is later, built in the 1290s (figs 78 and 79). The wheat barn shows some significant technical improvements even though it was built only 60 years later than the barley barn. In timber building, structural capabilities are determined by the carpenter’s ability to make strong joints. In early timber structures these were simple lap joints (one timber resting on another), but the Cressing barns show that during the late 13th century these simple joints were largely superseded by mortise-and-tenons and stronger types of lap joint. Moreover, the timbers were squared and more regular, and the structure was much better integrated, with all the elements soundly jointed together. These advances made possible the construction of very large barns for 1,000-acre estates such as Temple Cressing.23

Fig. 79 Temple Cressing, Essex, The Wheat Barn, interior. Squared timbers made more regular and integrated structures by the end of the thirteenth century.

Towns

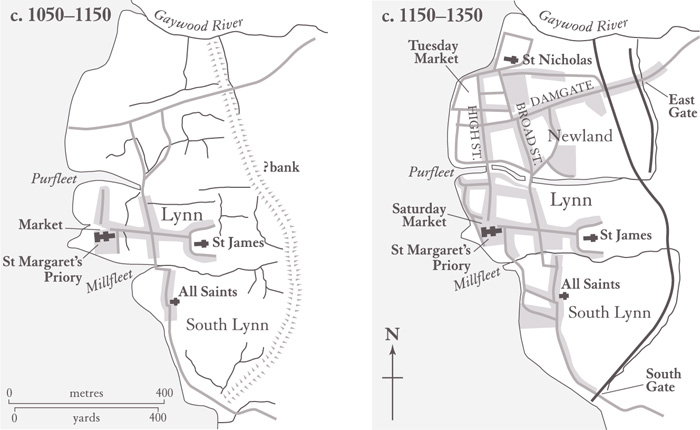

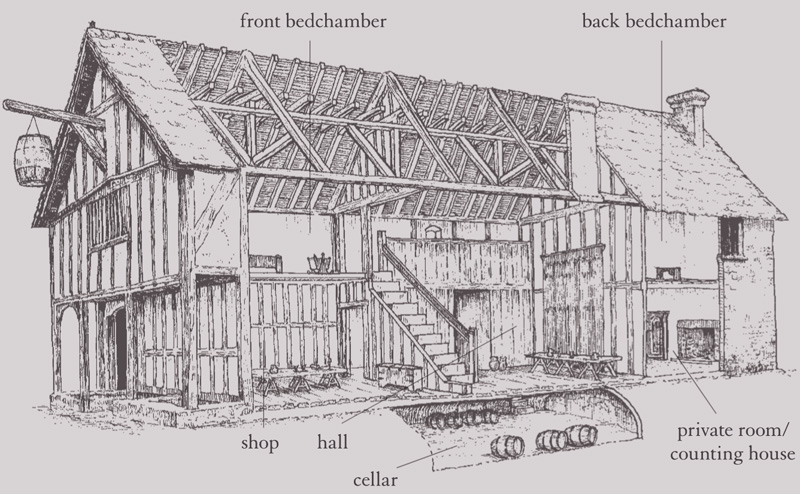

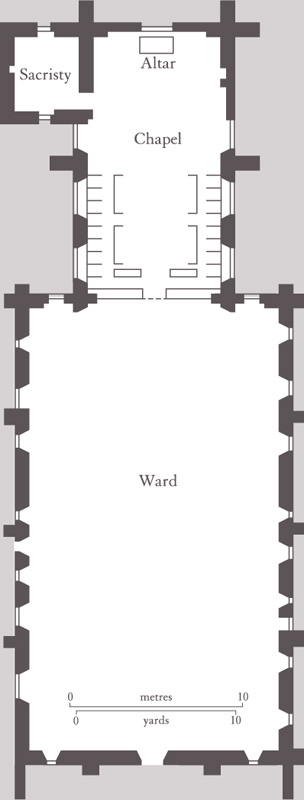

Between 1100 and 1300 the percentage of the English population that lived in towns doubled to 20 per cent. In 1086 there were about 100 boroughs, almost all founded by royal will. By 1300 there were more than 500, many founded by the Church and the aristocracy. Towns were profitable business; rents from the burgesses were good, but landlords could also profit from market tolls and the borough court. The example of King’s (originally Bishop’s) Lynn, Norfolk, demonstrates this nicely. In 1090 Herbert de Losinga, Bishop of Thetford, established a priory and market in the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Lynn. His intention was to capture a slice of the trade that would flow through the Wash and down the Great Ouse. The settlement was a success, and in about 1150 Bishop Turbe built an extension to the town, with a colossal new marketplace and a huge church. This was under the direct lordship of the bishop and was highly lucrative, so much so that the bishop bought back his rights over the original town and obtained a royal charter for the unified settlement in 1204 (fig. 80). A charter meant that the bishop could govern the town and collect taxes in exchange for a fixed fee paid to the Crown.24 The excavation of early medieval timber houses in Lynn, London and several other towns corroborates what the great barns at Cressing Temple tell us, which is that in the late 12th century timbers became squarer, cut by saw, mortise-and-tenon joints start to become common, frames were more stoutly constructed, with regularly spaced studding, and earth-fast posts were replaced by timber sole plates, often on foundations. This was all part of a process that led to fully self-supporting frames for domestic dwellings. The impetus for structural and technical advances, and the reasons for them, were not simple. On the one hand, they were driven by the need to solve intensely practical problems. For instance, the making of timber revetments that formed the London riverfront led to innovations in timber framing, their constructors having to battle against the intense forces of the tidal Thames. On the other hand, high-level patronage from bishops (as at Hereford), deans (as at Salisbury) or by the king himself (at Westminster) made stylistic and engineering demands that constantly pushed carpenters to the limit of their confidence. Technical improvement in the construction of timber town buildings was important as it changed the appearance of English towns. Earth-fast timber houses needed to be replaced or completely refurbished every 15 or 20 years as their foundations rotted. Timber-framed structures built on stone foundations lasted much longer – indeed, when well maintained, for centuries. Thus, owning a townhouse was now not merely the simple possession of a plot of land, it was a long-term investment. This meant that greater efforts were made in the building’s appearance and decoration, its maintenance, and its visual and spatial relationship with other buildings. Houses got taller, too. Timber framing meant that they could be built three storeys high; the first medieval domestic skyscrapers were constructed by the 1190s, and soon after their upper floors began to be jettied out (fig. 81).25

Fig. 80 King’s Lynn, Norfolk; maps showing the expansion of the town after 1150. As a consequence the town today, unusually, has two market places (Tuesday and Saturday)and two very large churches, the original parish church St Margaret’s and a chapel of ease St Nicholas serving the town extension.

Fig. 81 28 Cornmarket St, Oxford is a three-storied 15th century house with cellars. All floors were originally jettied but the ground floor has been under-built. There is a handsome corner post.

Fig. 82 Lady Row, York was a commercial development built in around 1316 in Holy Trinity Churchyard as an endowment for the chantry of the Blessed Virgin in the church. They are the earliest timber buildings in York and are a very early example of jettying.

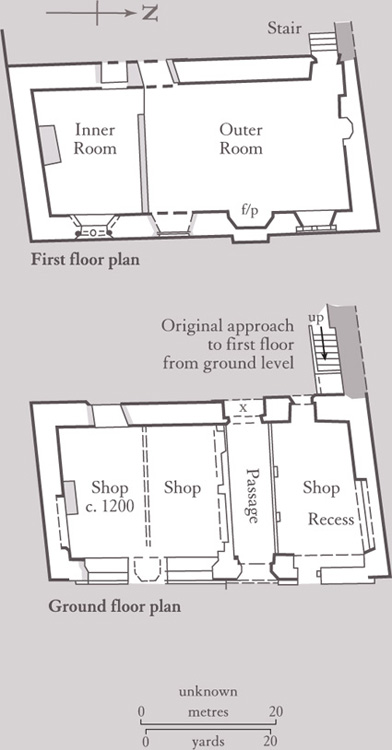

Many townhouses were also shops. Trade was, of course, central to the purpose of towns; by 1234 Canterbury had 200 shops and by 1300 Chester had 270. But, as today, London was England’s shopping Mecca. Its principal shopping street, Cheapside, was 450 yards long and 20 yards wide. The shops, 400 of them lined on either side, were occupied by goldsmiths, mercers, drapers, spicers, saddlers, girdlers, chandlers, wiredrawers, bucklemakers, pursemakers, buttonmakers and more. The shops themselves were very narrow, typically only 6ft to 7ft wide, and about 10ft to 12ft deep. Elsewhere in the city, where land was less valuable, shops were wider, their frontages measuring between 15ft and 20ft. The shops had a window opening and a narrow door, and window shutters were lifted during the day to reveal large, round-headed openings. Most shoppers would have been served standing in the street, rather like in an Arab souk today. Jetties overhead would have kept off the rain. Like a souk, too, the interiors were crammed with goods, and merchants’ houses elsewhere in the city would have acted as warehouses to supply them. Most shops were of timber, but some party walls and some larger shops were of stone.26

No early medieval shops survive today unaltered and so we have to study later examples to get an understanding of how retail premises originally looked. Lady Row, Goodramgate, York, is a row of shops dating from 1316 that have lost their original windows (fig. 82). Lady Row is not untypical of what we know of commercial developments of shops built by single landlords and then rented to shopkeepers. The upper rooms may have been separately let as housing, or traders may have lived above their showrooms. A rare survival from c.1350 is 169 Spon Street, Coventry, a different type of shop, probably built by a merchant with a showroom on the street and a substantial house with a hall for the family behind (fig. 83).27

Fig. 83 169 Spon Street, Coventry. Although restored in 1970, this shop is a rare survivor from the 1350s in a district of Coventry devoted to the cloth and leather trades. No medieval shop in England survives with its original ground floor openings intact.

But it was a different sort of building boom to the one stimulated by the Conquest. There were now proper quarries, better-skilled masons (and more of them), and few buildings were started anew. New monasteries were rare and, after the 1130s, no new dioceses were created until 1547 – only Salisbury Cathedral stands out as an entirely new structure. Most churches and castles were reconstructions, adaptations and extensions of existing buildings. Architectural leadership lay firmly with the cathedrals, whose golden age it was. These institutions were in cities, meaning that their influence in terms of architecture – as well as learning, ideas and education – was more profound than even the greatest of the rural monasteries. While most cathedrals were progressively rebuilt in new styles, many rural monastic churches remained Anglo-Norman.31