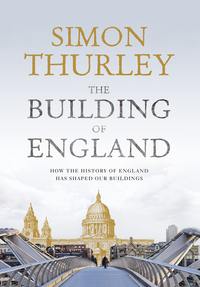

Fig. 26 Wharram Percy, Yorkshire. Layout of the 10th–11th-century settlement showing the main street with peasants’ plots running back to the four big common fields behind. The two manors, church, mill and village green are all shown. Before the 10th century almost everyone lived in scattered settlements of no more than a score of people. But between the 10th and 12th centuries in the central arable areas of England peasant farmers abandoned their farmsteads and hamlets and moved to create villages. These normally had a church, a main street, and between 12 and 60 houses. Outside this central village belt, in the east, the south-east, the north-west and the far south-west, people lived in various types of hamlets or single farmsteads. The now-deserted village at Wharram Percy, Yorkshire, was laid out in the 10th century by its landlords (fig. 26). The peasants lived in houses set on either side of a main street, at one end of which was a timber church and at the other was the village green with a common animal pound. Two manor houses sat hugger-mugger with the houses of their tenants. Each peasant family had a rectangular embanked enclosure or toft. The tofts normally contained a single peasant house. These houses were divided into two: the larger half with a hearth for the family and, on the other side of a cross passage, a byre for their livestock. The buildings were not materially different from earlier Saxon peasant structures.23

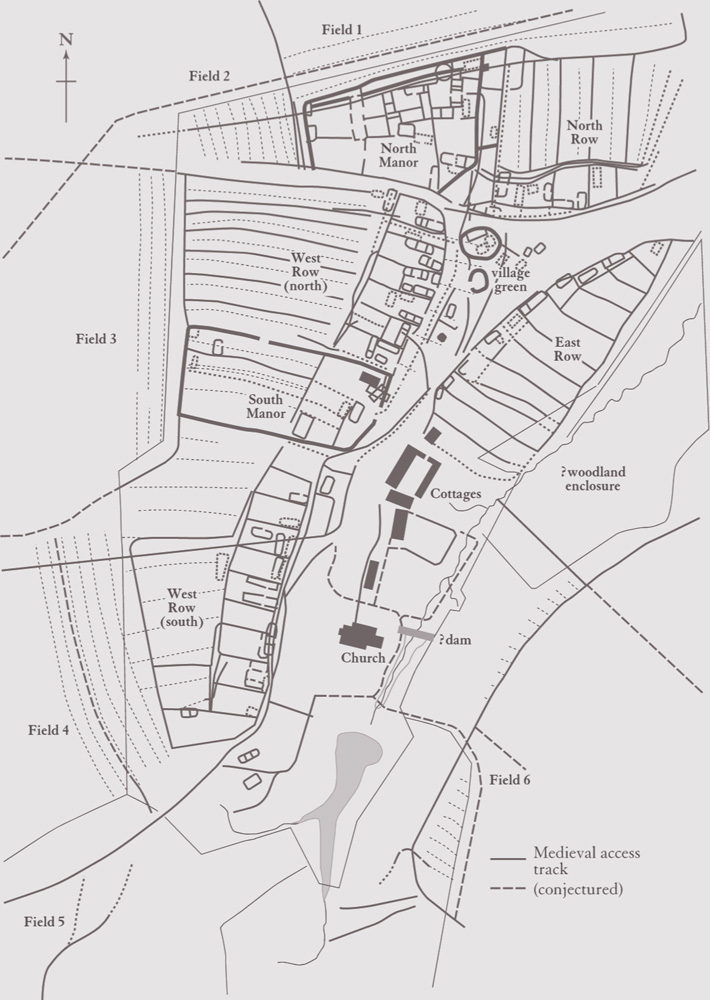

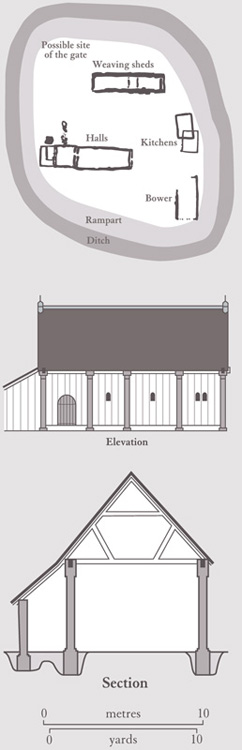

Goltho, Lincolnshire, known to the Saxons as Bullington, where a substantial fortified lordly residence has been excavated with a hall, kitchen and bower (private retreat) as well as weaving sheds where wool from the lord’s estates would be turned into cloth. Below, reconstructed section and elevation of the hall at Goltho built

c.1000–1080. There is no single national factor that led to the formation of villages such as Wharram Percy in this period. For many villages the causes were different, even unique, yet there were strong, common centripetal forces. As the density of rural settlement increased and the intensity of farming became greater, the countryside became crowded and complicated to work in landholdings that were shared by a number of family members. At the same time landlords created a kernel around which to group by building themselves large houses and founding churches. At root these changes express a changed attitude to property and land ownership that saw a delineation on the ground – by banks, fences and hedges – to demonstrate who owned what.24 The village belonged to landlords, and they would divide their land in two: the land worked by peasants, in exchange for cash rents and for labour, and the land farmed by the landlord himself – the demesne. At the centre of this stood the landlord’s manor, which originally meant simply a house but later came to mean all the rights and property owned by the lord. Agricultural production in central England was eventually regulated by rules that seem to have developed concurrently with villages. Every household had its own landholding equally dispersed across the village in one or other of the large ‘common’ fields made up of strips of land (furlongs). Each year one of the two or three common fields would be left fallow and on this would be grazed sheep. The following year the fallow field, enriched by manure from livestock, would be turned over for sowing and one of the others used for grazing the sheep. The principle behind this was twofold: first, when the land was being cropped, it was in sole ownership, but when it lay fallow it was in common use. Second, to achieve common grazing the sheep had to be held communally in a single flock, although they were individually owned. Thus the system relied on close communal cooperation and mutual trust in order to obtain maximum economic benefit. The trust extended to landlords, too, as the demesne lands also benefited from communal flocks.25 This system was very successful and contributed to a doubling of England’s population to 2.3 million between the time of Alfred and the Domesday survey of 1086. Agriculture yielded a surplus to feed the 10 per cent who now lived in towns, and peasants could pay cash rents to their lords. But, crucially, from the 8th century the common fields system was based on the folding of sheep. The development of breeds with fleeces better than those of the French or the Flemish created England’s staple export – wool. Wool was to make England the richest country in Europe, with a strong and stable silver currency.26 Much of this wealth flowed into the hands of the landlords, who invested it in building houses and churches for themselves. At Goltho, Lincolnshire, a Saxon lord’s residence has been excavated between the church and the village. Goltho was occupied from about 900 until the middle of the 12th century. The excavators found, beneath a Norman castle, a whole series of Saxon buildings belonging to the landlords of Goltho, who knew the place as ‘Bullington’. In the late Saxon period there was a great communal hall with a separate residential lodging house next door, a kitchen and several domestic buildings. The whole was surrounded by a deep ditch and a rampart topped with a timber palisade (fig. 27). The use of earthworks and timber palisading was increasingly adopted after 1000. The prehistoric mound at Silbury constructed in the third millennium BC was used in the 1010s and 20s as a fortified residence. Indeed it is possible that many so-called mottes, traditionally dated to the years following 1066, might in fact have been used as fortified residences by Saxon lords.27

Portchester, Hampshire. The Roman coastal fort here had probably never been completely abandoned and some parts within the Roman walls had been ploughed and used for crops. During the 10th century a substantial house was built, partly of stone, the residence of a thegn – a man of knightly rank. A few residences were built of stone, as at Portchester Castle, Hampshire. Here, perhaps from the 980s, a lordly residence was constructed within the Roman walls, which stand to this day. A large timber-aisled hall and three smaller timber buildings, a well and a latrine building were arranged around a courtyard with a freestanding stone tower in the corner (fig. 28). Here, as at Goltho, the hall would have been for communal feasting and entertainment, and the smaller halls for the lord and his lady’s more intimate use. In the construction of their great halls these fortified residences both used the same structural techniques that had been common since Roman times.28 But, looking forward, these residences were part of a very important shift from the Saxon concept of communally defended places, such as King Alfred’s burghs, to private fortified dwellings. The great residences did not stand alone. They lay at the centre of agricultural estates and were accompanied by farm buildings, the most important of which was the watermill. This was a significant source of revenue, as tenants were obliged to use their lord’s mill and pay a charge for the privilege. By 1086 there were 6,082 mills in England, many of which dated back to the 7th century. The technology was Roman, and it is likely that after 410 watermilling did not die out. The principle was simple: fast-flowing water powered a waterwheel that turned a mill stone on top of another stone. Corn was poured into a hole in the top stone and came out at the sides as meal. The waterwheel could either lie horizontally in the stream or, much more efficiently, be sited vertically. A large and ambitious mill, probably connected to a late 7th-century royal manor house, was excavated at Old Windsor in the 1950s. It had three enormous waterwheels set in a ditch (or leet) 20ft wide and 12ft deep. The leet was cut from a bend in the Thames three-quarters of a mile away. Many much smaller places, such as Wharram Percy (fig. 26), would have had less ambitious mills erected by landlords and used by the whole community.29

The Rise of Local Churches

For many Saxon landowners who were planning a village, building a manor house and founding a church would be inextricably entwined as these were all part of an economic, social and religious enterprise. Before the 10th century minsters had dominated the religious landscape, but by the 940s secular lords, with their coffers swelled by profits from their lands, increasingly began to commission their own churches. Many parish churches today have their origins as estate churches of an Anglo-Saxon landlord, which is why many parishes have boundaries that are the same as those of Saxon estates. The remarkably well-preserved church of St Peter, Barton-upon-Humber, Lincolnshire, is one such building. Built originally as an estate church next to a lordly fortified enclosure, it comprised a central tower flanked by a chancel in the east and a baptistery to the west (fig. 31). The chancel and baptistery were two-storeyed, and the tower had three storeys. This was not just a place of worship; it was a symbol of the lord’s status, a place for his heir to be baptised.

Fig. 29 All Saints’, Earls Barton, Northamptonshire. Like St Peter’s, Barton-upon-Humber, the tower of All Saints’ is set with a pattern of long thin stones used by the masons both structurally and decoratively as if they were timber beams. As at St Peter’s, the rest of the church is of a later date.

All Saints’, Earls Barton, Northamptonshire (fig. 29), is another example of a magnificent church conceived and built by a Saxon noble. What is now a parish church originally had its nave on the ground floor of the tower and a small chancel to its east. The floors above the nave are referred to as a belfry; the term today is solely associated with bells but in Middle English it meant something like ‘place of security’. This was perhaps where relics, vestments and plate presented to the church by its patron were stored.

Late Saxon stone-built church towers were not only status symbols and strong rooms for their patrons but were also linked to the evolving church liturgy. In the development of parish funeral rites the use of bells became increasingly important. Bells were rung as the body left the church as well as when it reached the graveside, drawing God’s attention to the prayers of the faithful and sending the deceased’s soul forth to heaven.30 Some belfries, such as the one at St Peter’s, Barton, were topped with timber spires. None of these survives today, but at St Mary’s, Sompting, Sussex, the late Saxon spire was rebuilt in the 14th century to the same pattern (fig. 30). Typically, such spires were supported by a central mast resting on a horizontal beam on the tower top; they were almost all shingled and had a characteristic shape known as a Rhenish helm. This type of pinnacle, and the central mast construction, link the design of these spires to those of Carolingian Europe.31

Fig. 30 St Mary’s, Sompting, Sussex. Although this church has a 14th-century spire, it captures the appearance of late Saxon examples. Like both St Peter’s, Barton (which would have had such a spire) and All Saints’, Earls Barton, stone is used on rubble walls like timber.

It is not known how many local churches were built by Saxon lords before the Conquest, but the majority of churches around which the parish system formed were in existence by around 1120. In total they numbered about 6,000 to 7,000 buildings. This was a major change to people’s way of life and to the appearance of the countryside. Previously, people had travelled perhaps as far as ten miles to one of approximately 800 minster churches to worship. Now, for most, there was a church in their village or town.

Building Techniques and Materials

As this chapter has demonstrated, building in England begins to diversify and become more complex from the reign of Alfred the Great. This was a process that was driven by richer, better-informed and more powerful patrons. According to King Alfred’s contemporary biographer, the king ‘did not cease … to instruct … all his craftsmen’, and King Eadred (946–955) specially went to Abingdon Abbey ‘to plan the structure of the buildings for himself. With his own hand he measured all the foundations of the monastery exactly where he decided to raise the walls.’ A manuscript from about the 1030s shows Anglo-Saxon craftsmen at work on a complex building (fig. 32), with a spectrum of craftsmen and skills.

Fig. 31 St Peter’s, Barton-upon-Humber. The tower and baptistery to its left date from just before 1000. The nave and porch to the right are late 13th-century. The Saxon tower was heightened in the later 11th century; before this date the tower was probably crowned by a timber spire very similar to that at Sompting (fig. 30).

The most important phenomenon must have been the rise of the anonymous (to us) master builder or architect. The Anglo-Saxons used the Latin term architectus, not to describe an architect in the modern sense but to describe people with creative responsibility for a structure. Early buildings such as Wearmouth and Jarrow (pp 34–5) could be erected with minimum skill and engineering, but as buildings became more sophisticated masons, carvers and quarry owners became crucial and the designers had a much more onerous task. It would have been impossible to build great churches such as Winchester Cathedral, or even smaller ones such as St Mary’s, Sompting, without drawings and small-scale timber models. Drawings might have been on parchment, but equally they might have been etched into large areas of plaster floor expressly laid for the purpose. In the 9th century masonry components began to be cut at the quarry, and so templates must have been made and passed to and fro. Late Saxon builders were still heavily reliant on salvaged Roman stone. St Peter’s, Barton-upon-Humber (fig. 31), is typical in that its stone dressings were constructed using blocks of millstone grit possibly taken from the nearby Roman site at Winteringham or from further afield in York. The crypt at Hexham Abbey, Northumberland, contains carved Roman ashlars with inscriptions, and the nearby tower at St Andrew’s, Corbridge, contains a reset Roman arch. In towns the ruins of Rome were upstanding and visible, and at Winchester, for instance, provided most of the materials necessary to construct the cathedral. In the late Saxon period it is likely that there were well-organised salvage contractors, perhaps acting under royal licence, deconstructing Roman ruins and selling on the materials for reuse.

Whilst masons were not numerous in early Saxon England, by 900 there must have been hundreds of craftsmen working in stone. The most skilled were re-cutting large Roman ashlars into window heads, balusters and quoins. Most, however, were little more than labourers. Given the relatively small number of stone buildings in Saxon England and the proximity of most to Roman ruins, the quarrying industry remained underdeveloped. Most Saxon quarries were merely shallow diggings producing huge quantities of rough rubble – the most common stone-walling material. Rubble walls could be built with a small number of technicians and a large number of unskilled labourers; such walls also relied on the skills of joiners rather than masons. Rubble was mixed with mortar and shovelled into timber shuttering; a third of the mix was mortar and this had to dry before another layer of rubble mix could be added on top. Sometimes levelling courses were put between layers of rubble, and these were often of Roman brick or tile, or perhaps herringbone masonry. Corners were now and then strengthened and straightened by stone quoins, this being known as long-and-short work. A church tower such as St Katherine’s, Little Bardfield, Essex, was entirely built of rubble in diminishing stages. Here not even the window openings had stone dressings.32

Most rubble walls were originally plastered inside and out, concealing the original construction method. This provided a canvas for surface decoration as seen at towers such as All Saints’, Earls Barton, or St Peter’s, Barton-upon-Humber (figs 29 and 31). This decoration, whilst imitating Roman arcades and pilasters, was easily applied and constructed using the principles of joinery. Even the baluster window openings at All Saints’ were conceived in the language of wood turning rather than masons’ work.33 Thus the role of carpenters in construction was crucial. They built the shuttering for wall construction and scaffolding as the building rose, in addition to the roofs (many of which were covered in timber shingles), doors, windows, balconies, staircases and other internal fittings. Moreover, the decoration of these structures was imagined in the mind of a carpenter not a mason. Finally, it is vital to acknowledge the increasingly important role of the smith in construction. Smiths were highly valued, largely through their role of arming men in a military society. Yet buildings increasingly demanded both decorative ironwork and more functional bars, cramps and hinges.

Fig. 32 God witnessing the building of the tower of Babel; a manuscript from St Augustine’s Monastery, Canterbury, Kent from the second quarter of the 11th century. This is a rare glimpse of Saxon workmen with their tools erecting a complex building (from The Old English Illustrated Hexateuch, c.1125–50, British Library. Shelfmark: Cotton Claudius B. IV, f. 19).

The Viking raids shook English society and stimulated the growth of the state. First the Mercians, then the West Saxons, mobilised labour and materials to reshape society and the very landscape of England. The country was divided into 32 shires, at least 20 of which took their names from burghs, which became centres of royal power and administration. Beneath these were smaller administrative units: hundreds in the south and west, and wapentakes in the north and east, the focus for justice and tax collection. The only exception was the north, which was only brought into the system after the Norman Conquest.

As the administrative matrix of England was created from above, so parishes formed from below. Instead of holding all the land themselves, kings granted it to their followers, who became the first generation of estate-owning English squires. These men built themselves fortified houses and founded churches and, across much of lowland England, this stimulated the move from dispersed settlements to villages. People’s religious focus and loyalty also moved from the minsters to new parishes in both town and country. The sense of identity these changes created is of huge importance; by 1000 it was not only England that existed but also a sense of Englishness among its inhabitants. These were big changes and they were accompanied by important architectural developments. Alongside a timber-building tradition that was part Roman and part Saxon, a vigorous stone tradition developed. In this, before the 1040s, English buildings were eclectic combinations of strong insular traditions, themselves established through a mix of Romano-British and Saxon forms – with influences from Carolingian Europe – producing an architecture that was wholly English.34

There was, however, a strong underlying continuity. Although life had become more complex both economically and socially, rich and poor still lived in single-cell dwellings. Peasants, either in villages or in isolated houses or hamlets, lived in a single room in which they would cook, eat and sleep. Although their social and economic superiors had separate structures for communal entertainment, worship and cooking, they also lived in a single room, albeit constructed more robustly and decorated in the current fashion. This fact continued to be the foundation of everyday life for some centuries to come.

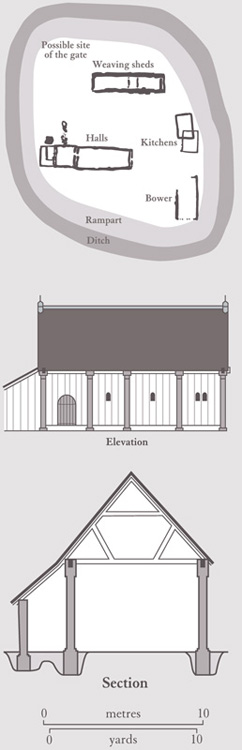

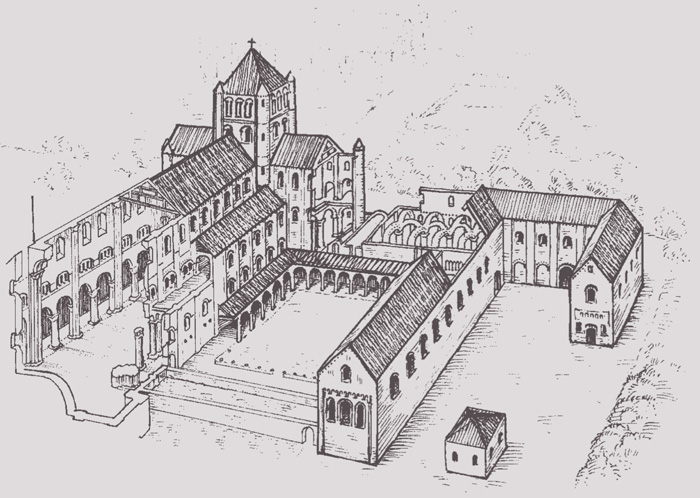

As the first generation of Normans died out, England’s architecture was already looking very different to anything in their former homelands ... they might not have been able to express it in 1130, but the Normans and their architecture were becoming English. Although King Alfred’s dynasty succeeded in forging a single English state, it could not eliminate the threat from foreign predators. As a result, the kingdom was overthrown in the 1010s by the Danes, and from 1019 England became part of a Scandinavian empire ruled by King Cnut and his sons for 26 years. The house of Wessex was only restored in 1042 with the accession of Edward the Confessor. By this date England, as a unified kingdom, was one of the best-developed monarchies in Europe and probably the richest. It had a strong currency and efficient taxation, effective administration, laws and judicial system, more than 100 towns, and was home to some of the largest and most sophisticated buildings in northern Europe. The conquest of the English state by the Danish kings prefigured the Norman Conquest by half a century. That William of Normandy’s success lived on where Cnut’s conquest was short-lived was a result of the stability, strength and close proximity of the Norman homeland. Yet for a quarter of a century the cultural orientation of England bent towards Scandinavia, opening the way for architectural and decorative influences. It is sometimes possible to detect these in sculpture and the decorative arts, but harder in architecture. It is likely, though, that the distinctive round towers of parish churches in Norfolk and Suffolk can be connected with missionaries coming from Saxony after the Danish invasions, but this is an isolated example, and the enduring architectural impact of the second Viking era was limited.1 Edward the Confessor The same cannot be said for the reign of Edward the Confessor, who commissioned one of the most influential buildings in English architectural history. Edward’s outlook was cosmopolitan. His mother was the daughter of the Count of Normandy and Edward had been brought up in the Norman court for 25 years. Out of a plethora of claimants for the English throne Edward was eventually crowned in 1043 and ruled, with some success, for 23 years. It was soon after his accession that he decided to build a new palace and abbey at Westminster. This was a break with tradition for, as a son of Wessex, Edward had been crowned at Winchester Cathedral, the burial place of his ancestors and his Danish predecessors. By the 1040s, however, London was the most important and populous city in England. It occupied a key defensive position, had the largest mint, was the biggest port, and contributed more in tax than anywhere else. Moreover, its citizens had taken a role in the acclamation of kings, choosing Edmund Ironside in 1016 and Edward himself in 1042. Edward was a realist and he saw that London, not Winchester, was now the key to the kingdom. His new palace and abbey, both built – presumably for security – outside the city, created a powerful royal enclave next to England’s commercial and political capital. The thoroughness and scale of the enterprise were startling. The existing minster was entirely demolished, new quarries were opened up at Reigate and craftsmen were assembled from all over England. Building was underway before 1050, but whilst the east end was ready to receive the Confessor’s body in 1065 the whole abbey was not completed until about 1080. The abbey church was enormous, about 322ft long, larger than anything built in England since the Romans, and larger than any church in northern Europe at the time. This reflected Edward’s wealth and his desire to establish, in London, a royal dynastic centre to rival if not surpass Winchester.2 Fig. 33 Conjectural reconstruction of Edward the Confessor’s Westminster Abbey showing in cut-a-way the nave arcades. This was a new way of building in England transforming the three-dimensional experience of internal space. The Confessor’s Westminster Abbey sent English architecture in a wholly new direction. The abbey had no direct precedent in England or Normandy, although, across the Channel, the Norman abbey of Jumièges was being constructed in a similar style almost simultaneously. Both the English and the Normans were in fact imitating a way of building invented in Burgundy, and developed there and in the Loire valley in the 1030s and 40s. The essential change was from interiors that relied for their effect on large areas of painted wall surface to spaces that were modelled in three dimensions, with arches, horizontal mouldings (string courses), semicircular shafts, stone vaults and ornamental mouldings. These ideas essentially came from Roman buildings, especially the large and prominent remains of amphitheatres with their tiers of arches and columns.3

Fig. 34 St Mary in Castro, Dover Castle, Kent. Standing next to the Roman lighthouse that dates from the early 2nd century is a Saxon church, itself substantially built of re-used Roman materials. It was once linked to the lighthouse which was probably used as its bell tower. Its location at the centre of an important fortified burgh together with high-level patronage meant that it was one of the most substantial churches of its age.