The Building of England: How the History of England Has Shaped Our Buildings

Quarries were key to the building industry. Stone was not only extracted there, it was cut and carved. Blocks of ashlar, columns, bases and capitals were mass produced and shipped directly to the site, thereby avoiding the transport of stone that would end up as chippings at their destination. Working at a distance was, in principle, familiar, as the components of timber buildings were often cut remotely, transported and erected on site; but the precision needed for stonework was much greater. The dimension of each course of stone, for instance, had to accord with any decorative or structural elements in it. So ashlars had to be cut to different dimensions in the correct quantity. These details had to be carefully calculated and communicated to the quarry by means of written instructions and templates. The quarries therefore also became training schools, producing masons and carvers who could move to the great building sites, where they could learn to set stone and undertake some of the more exacting work that was done on the bench in masons’ lodges on site.30

In Normandy as much as in England the quality of masonry improved markedly in the hundred years after the Conquest; larger blocks, tighter joints, finer carving suggest more skilled design, increasing proficiency among masons and better tools. It enabled the shift from the austerity of Winchester to the exuberance of Durham. Yet architecture after 1066 was as experimental as the Saxon work that preceded it. From 1000, people increasingly became used to seeing and experiencing stone buildings, but this should not obscure the fact that even after 1066 timber remained the most important and common building material. Although most churches were now built in stone, the first generation of castles – and almost all domestic, agricultural and industrial buildings – remained of timber. Stone buildings, too, contained huge quantities of timber; the earliest timber roof to survive intact is at St Mary’s, Kempley, Gloucestershire. It dates from soon after 1120 and comprises fifteen trusses, with sole-plates projecting into the church that were probably carved with animal heads.31 Other fragments of early timberwork survive, including the unusual and handsome nine-bay balustrade of c.1180 at St Nicholas’s, Compton, Surrey, and a door of c.1050 in Westminster Abbey.32

The construction of the great Norman cathedrals was overseen by masons who we would today call architects. After 1066 their names are increasingly known: Blithere at Canterbury, Robert at St Albans and Hugh at Winchester. These men understood the principles of engineering, not through the written word, but through observation and trial and error. They drew plans, sections and templates either on parchment, wood or on large plaster panels. The earliest English architectural drawing to survive (of c.1200) is at Byland Abbey, Yorkshire, where incised drawings on a floor slab and a wall are full-size sections of the west front rose window.33 In addition to drawings, designers commissioned models and templates, either at reduced scale or sometimes full-size.

It has been said that by looking at buildings alone it would be impossible for a historian to guess that the Norman Conquest had taken place. In 1000 England’s architecture had already reached a turning point and the changes that came rapidly after 1066 had been in embryo since the 1050s at the latest. Yet without doubt the Conquest hugely accelerated architectural change. The building and craft industries quickly developed and diversified, and by 1130 almost everyone could experience stone architecture in their own locality. The great Saxon estates had been broken up and, as well as the great magnates, there was now a large class of middling landowners who aspired to build themselves homes and churches.

The severe unsullied monumentality of early Norman buildings as seen in the transepts of Winchester or the elevations of the White Tower lasted merely a generation; they soon gave way to something more florid and playful. Likewise the reforming aspirations of the Norman churchmen were diluted and what remained was an English compromise. As the first generation of Normans died out, England’s architecture was already looking very different to anything in their former homelands. Indeed, the men and their families were feeling different, too. They might not have been able to express it in 1130, but the Normans and their architecture were becoming English.

As the second generation of Normans felt more English, so the great cathedrals, abbeys, castles and houses then under construction became increasingly distinct from their counterparts in France.

The Normans and the English

Many thought the death of Henry I in 1135 a calamity. He was the Conqueror’s last surviving son and was outlived by only one legitimate child, Matilda. Matilda was his agreed successor but his nephew Stephen darted across the Channel and was crowned before he could be stopped. This led to a period of disorder and uncertainty, often called the Anarchy, which was only resolved by Stephen’s death and the accession of Matilda’s son, Henry II, in 1153.

Henry II had huge strength of character, boundless energy, and a determination to re-establish order and the rule of law. His court was cosmopolitan and, through his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, he presided over territories from Scotland to the Pyrenees. Henry was not a Norman king; he had Anglo-Saxon ancestry through his mother, and of his eight great-grandparents only William the Conqueror was Norman. But it was not only the monarchy that was no longer Norman. Families whose ancestors had arrived with the Conqueror had begun to see themselves as English; while the first generation of newcomers had usually been buried in Normandy, by the 1150s their children and grandchildren were buried in England.1

A sense of Englishness also becomes increasingly apparent in the work of a generation of historians writing between about 1120 and 1150. Henry of Huntingdon, for instance, set out to write the history of ‘this, the most celebrated of islands, formerly called Albion, later Britain, and now England’. His History of the English continued up to his own time and explained that the past victories of the Normans, including the Conquest of 1066, were now English history. This was in many respects true. The Norman ruling elite had married English women, adopted English laws and customs, assimilated native administrative structures, appropriated English history as their own and made pilgrimages to the shrines of Anglo-Saxon saints. In fact, although they didn’t speak English as their first language, the third generation of Normans were now Englishmen.2

Despite Henry II’s strength and success, he, no more than William the Conqueror, could control events after his death, and his sons Richard and John frittered away the territories and powers amassed by their father. Yet in many senses the reigns of Henry’s sons saw a further reinforcement of English identity: King Richard’s absence in 1191; the loss of Normandy in 1204; the interdict of 1208 (when the pope banned the administration of the sacraments in England) and the failed invasion of England by Prince Louis of France in 1216 – all these led to increasing insularity and even xenophobia.

This reinforcement was of great importance for the development of English architecture in the century or so after 1130. The growing wealth, self-confidence and identity of the English ruling class led to an energetic patronage of architecture. Magnates reorganised their estates, built themselves castles, and endowed churches and monasteries; bishops reconstructed their cathedrals and abbots built new abbeys. The style in which these buildings were constructed was ambitious, original and, with hindsight, English.3

Old Principles, New Fashions

The 1150s, 60s and 70s were a period of stylistic experimentation. New currents of design from France, mixed with native decorative and structural traditions, produced some of the most inventive and lively buildings ever constructed in England. Contemporaries recognised this but might have described what was happening in different terms to us. For them, architectural language was important as it expressed hierarchy. In the Middle Ages most high-status architecture was about the ritualised display of power: ceremony, ritual and liturgy were the driving forces behind the appearance of buildings. Their structure and decoration expressed social, economic and religious hierarchies, and so the architectural setting of an activity, whether it be dining or praying, had to match its importance – and the importance of the people who were doing it.4 This could be achieved through progressive intensity of decoration, the least important places being plain and the most important richly decorated, or through association, either with past activities or people, or with Christian Rome. Various parts of buildings – and whole buildings themselves – were thus always accorded a status through their architecture. So, for instance, as the most important of all medieval secular spaces was the great hall, this was singled out for special treatment. The magnificence of the carving around the doorway to Bishop Puiset’s Hall at Durham Castle, and the arcading in the room above (fig. 56), proclaim them to be of the highest importance. English great halls, unlike some of their continental contemporaries, were always roofed in timber rather than vaulted in stone, a sign of status and reflecting a tradition going back to Roman Britain.

In religious buildings presbyteries and shrines were the most important areas, and, even in the most humble parish churches, were given significance by their decoration. Antiquity conferred status, too. When the Lady Chapel at Glastonbury burnt in 1184 its replacement included Anglo-Norman (or earlier) stylistic elements to emphasise its importance and venerability. We have already seen that references to ancient Rome were a way of emphasising hierarchy (p. 69). When the east end of Canterbury Cathedral was rebuilt the great Purbeck piers were given Roman proportions, bases and capitals, echoing the early Christian basilicas of Rome (pp 94–5).5

Fig. 58 Byland Abbey, Yorkshire; reconstruction of the nave as first built. The stalls for the lay brothers were integrated into the lower part of the nave arcade. The prominent rose window, 26ft across, was an architectural elaboration that the earliest Cistercians would have disapproved of.

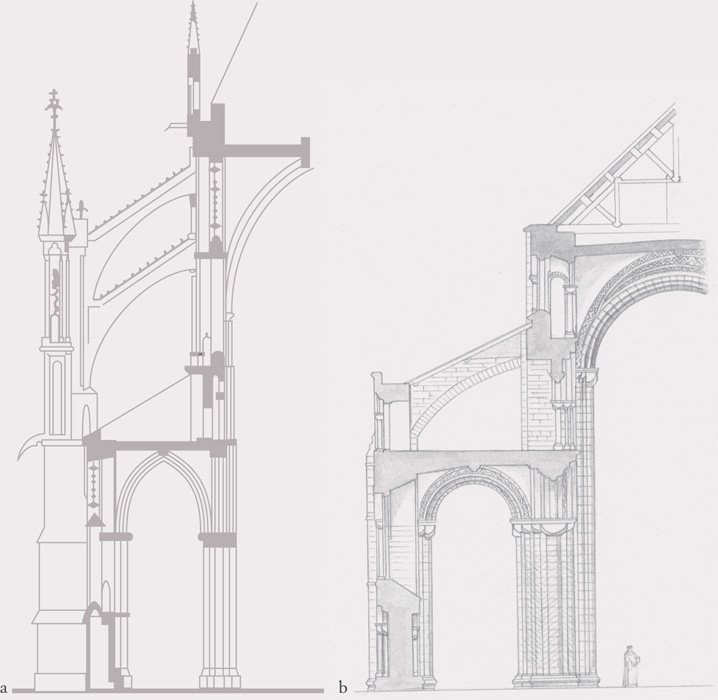

By 1170 work had started on Byland Abbey, the most ambitious Cistercian church of its age. This was no austere box. The walls were enlivened by three levels of pointed arches supporting a timber barrel vault; the west end was illuminated by a great rose or circular window. (fig. 58). But the architects of Byland were not using Gothic features as an alternative structural system like the French; they used them as an alternative form of decoration. This was the first manifestation of English Gothic, retaining the structural tradition of Anglo-Norman buildings but adopting the decorative vocabulary of Gothic architecture.

Fig. 59 Canterbury Cathedral, Kent, looking east; the choir of 1175–84. Its principal architectural characteristic is the height of the main arcade, more than half the height of the whole elevation; above are clusters of polished black Purbeck marble shafts used for the first time in England. These lead the eye up to the high vaults, in six parts, with decorated ribs that complement the beautifully carved capitals of the arcade far below. Beyond is the presbytery (fig. 60).

The adoption of Gothic detailing at Byland and then at York Minster was very influential in the north, but the repercussions of events at Canterbury between 1170 and 1175 were of much greater national impact. The most famous murder in English history took place on 29 December 1170 in Canterbury Cathedral; its victim was Archbishop Thomas Becket. Within days miracles were reported. The dead archbishop rapidly became a martyr and, within three years, a saint. This was a turning point in the history of Canterbury. Another took place eighteen months after Becket was canonised: the gutting of Archbishop Anselm’s early 12th-century choir by fire. This gave the Canterbury monks the opportunity to create a spectacular new setting for their saint and his relics. After consulting a number of architects, the monks chose a Frenchman, William, who came from the French city of Sens, the location of a new cathedral built in the Gothic style. As the monks wanted to ensure continuity with their much-loved building, he decided to retain the crypt and the lower, undamaged, parts of the choir and construct inside it a new east end.

So what was new about William of Sens’s choir (fig. 59)? Compared with the Anglo-Norman work of the nave the arcades were much taller, with gently pointed arches squeezing those of the gallery above. The vault springs from a low point and its ribs are decorated with dog-tooth motifs. The piers themselves were more slender and furnished with carved capitals. Polished limestone was used to enliven the elevations. William of Sens fell from his own scaffolding while supervising the construction of the highest vaults over the eastern crossing. He tried to carry on the work from his sick bed but had to return to France. His replacement was another William, known as ‘the Englishman’. He not only completed the repair of the fire damage but was commissioned to build an enlarged chapel to the east of it to replace the Trinity Chapel, the crypt of which contained the relics of St Thomas. This was to have two parts: the Trinity Chapel itself and beyond that a circular shrine called the Corona, where the severed crown of the martyr’s head was housed. The Englishman continued the main features of the choir through to the new chapel, which, being raised above a higher crypt, had shorter piers and much more satisfying proportions (fig. 60). The big windows were made possible by some of the earliest visible flying buttresses anywhere. The stained-glass scenes of the life of Christ and the miracles of St Thomas Becket are still largely intact, held in place by geometric iron frameworks (ferramenta). Their colours intensify the effect of the polished limestone columns, the use of which becomes progressively denser as the visitor moves eastwards. In the chapel the arcade piers are doubled-up and entirely made of Purbeck marble, while those nearest the shrine are of a hard pink-and-cream marble imported from abroad.

Fig. 60 Canterbury Cathedral, Kent. The presbytery was the culmination of the cathedral and the location of St Thomas’s shrine from 1220 until its destruction in 1538. The use of polished limestone made a huge impact on both pilgrims and masons from elsewhere. The survival of the original glass is nothing short of miraculous.

Fig. 61 Wells Cathedral, Somerset; the nave is now dominated by the scissor braces at the crossing added in the 14th century. Here the arcade and the clerestory are practically the same height and the triforium becomes a decorative band containing a denser rhythm of arches between the two. The effect of this was to abolish the rhythm of the bay structure and emphasise the great length of the cathedral, now, of course, interrupted by the scissor brace.

The experience of moving eastwards through Canterbury Cathedral towards the Corona is breathtaking. It is necessary to ascend steps over both Lanfranc’s and William the Englishman’s crypts to enter the extraordinary world of polished stone designed to evoke the heavenly Jerusalem in the Book of Revelation. A pilgrim would have felt as if he had been shrunk and placed inside an enamelled reliquary like the Becket casket in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Canterbury was to be influential, not so much through the details of its style or construction (although these were important), but for its lavishness. It was the mother church of England and set the standard for all that came after, particularly in its extravagant use of polished stones. Although Canterbury has more directly French features than any other English building of its age, its successors created a very different look, much more English and, in a sense, much more original. The rebuilding of Wells Cathedral was started soon after 1175 as a deliberate bid to replace Bath as the centre of the diocese of Somerset. It was sufficiently complete to be dedicated in 1239. Over a 60-year period it had at least three architects, all of whose genius must be recognised; for the building that they created was of huge originality and skill. It was the first building in England, if not in the whole of Europe, to be built with pointed arches throughout. But more important was the way the arches were handled. The overwhelming sensation gained by a visit to Wells is the horizontal effect of the nave created by three self-contained strata of arches (fig. 61). The lowest, the nave arcade, is supported by massive cross-shaped piers faced with 24 shafts bunched in groups of three. In Anglo-Norman cathedrals there was a substantial gallery above the nave arcades but at Wells there is the semblance of a triforium, which in French buildings is a much narrower passage in the thickness of the wall, fronted by an arcade. This arcade runs the entire length of the nave as a consistent band of decoration without vertical interruptions. Above is the clerestory, with the ribs of the vault supported on stubby shafts.8

Fig. 62 Lincoln Cathedral; the vault of St Hugh’s Choir of about 1200, the first instance anywhere of a rib that ran along the ridge of the vault. To this rib join ribs that have little structural necessity and do not define the bay structure – in other words, they are pure decoration.

Ideas from Canterbury and Wells fed into the greatest of early English Gothic churches: the cathedral at Lincoln. In 1185 a vault in the east end of the cathedral collapsed and the following year Henry II appointed Hugh of Avalon as the new bishop. These two events led to a rebuilding of the eastern parts, largely completed by the time of Hugh’s death in 1200. This probably finished the original plan; but work continued and by about 1250 the whole cathedral, save the Norman west front, had been rebuilt. Lincoln was rebuilt in its own image. This was a cathedral that proclaimed its place at the top of the hierarchy, together with Canterbury and York. As a result nobody stinted on money, scale or decorative effect. Lincoln set out to dazzle – and dazzle it does.