The Building of England: How the History of England Has Shaped Our Buildings

The earliest part to be rebuilt was itself replaced in 1255 by the Angel Choir, but St Hugh’s choir and eastern transepts remain. The first thing that strikes the visitor is the use of polished limestone in direct imitation of the work at Canterbury. The second thing is the form of the choir vault. The choir is still built with the thick walls, but the piers appear less massive than at Wells and the shafts from the vaults divide the elevation into bays. But the vaults do not reinforce the bay structure. For the first time there is a central rib running the length of the vault. Onto this, at seemingly random points, the transverse ribs join, creating a pattern that at first defies comprehension (fig. 62). This was not structural necessity, it was pure decoration. So at Lincoln ribs are used for the first time in an English way – as surface ornament. The nave vaults are slightly later and less idiosyncratic, but richer, denser, more complex and symmetrical. They succeed in making the vault as interesting and lively as the walls, bringing the whole together in a restless sea of ornament. The nave elevations below have extraordinary depth. This is not only achieved by passages in the clerestory and triforium but by the 27ft span of the arches, allowing a panorama of the aisle walls, which are deeply moulded with blind arcading. The effect is accentuated by the nave piers, each pair of which is subtly different.

The design of Lincoln, extraordinarily experimental and hungry for novelty, had a huge impact on the next two generations of English builders. In 1817 the Regency architect, Thomas Rickman, christened the style of Lincoln ‘Early English’, a term that nicely expresses the essential insularity of what was being built. The great churches described above, and the many others that followed them, were individualistic and original, taking French ideas and turning them into a decorative vocabulary unique to England. This concentration on elaboration and surface ornament was a development from the Anglo-Saxons through the late Anglo-Norman monuments into the first Gothic structures. There is a real sense in which, by 1220, a national style had been formed.9

Fig. 63 Castle Acre Priory, Norfolk the west front started in c.1130. Richly decorated with blind arcading; there were originally four tall windows in the middle, replaced by a single window in the 15th century.

Monasteries

The Norman Conquest did not lead to an immediate surge in the building of new monasteries. Patrons were too uncertain of their hold on England to invest in expensive new projects, preferring instead to donate English land to Norman monasteries. A small number of new monasteries were founded by the king and his richest followers. Of these perhaps the best preserved and most important is at Castle Acre, Norfolk. The small village of Castle Acre still retains the layout of an early Norman town. The house of its owners, the Warenne family, partly survives within the huge earthworks of the largely later castle, fragments of the town walls still stand, and just outside them within its own walled precinct lie the impressive remains of the priory. Land for the priory was given by William II de Warenne in 1090 but the church was only consecrated between 1146 and 1148, and the west front, the most famous and beautiful of all late Anglo-Norman façades, was not finished until the 1160s (fig. 63).

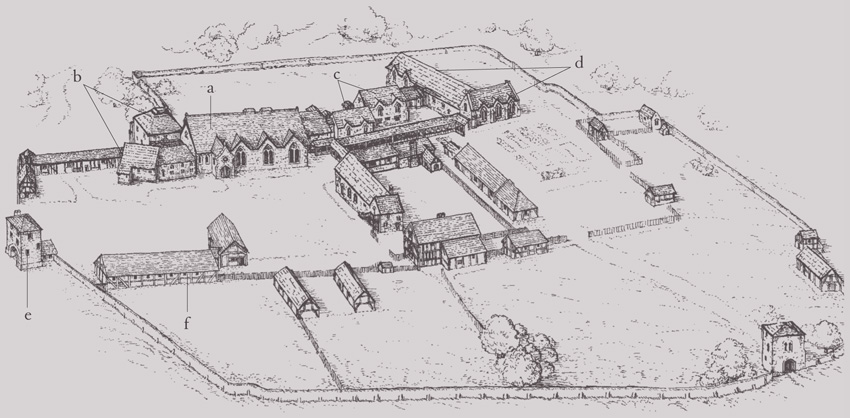

At its heart was the cloister, the great communal space of the priory. Here, between services, the monks could read, drawing books from a large cupboard on the east side. Regulated periods of Latin conversation were also permitted here, as were more mundane tasks such as hair cutting and washing clothes. Abutting the south transept was the chapter house, where the monks gathered each day to listen to the Rule of St Benedict being read and to attend to community business. This was the boardroom of a monastery and it was decorated to match its status. The walls at Castle Acre had interlaced blind arcading painted in bright colours.

The remainder of the east side of the cloister was occupied by a vast dormitory. This was raised up on a vaulted undercroft and at its south end had a remarkable two-storey latrine (or reredorter) with 24 seats. The monks slept fully clothed and descended by a stair to the church for the night-time offices. Below, in the day room, amidst the piers of the vaults, monks in winter could work and read. Detached from the dormitory, to the east was the infirmary, set aside for old or ill monks who received special care and rations.

The south side of the cloister contained the refectory, large enough to seat the whole community. This was a ground-floor room, which in secular buildings might be called a great hall. It had a dais for the prior and a pulpit from which lessons were read during meals. To its east was the warming house where, in deepest winter, a fire was lit on an open hearth in the middle of the room. To the west of the refectory was the kitchen; in the 12th century, monks cooked here in rotation. The vaulted ground floor west of the range next to the kitchen was used for storage of food and wine. Above was the priory guest house and a separate room for the prior. Next to this was the prior’s chapel.10

Castle Acre was a Cluniac priory following the rites and rituals of the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny in Burgundy. Other orders varied the layout of their buildings and the structure of their governance, but, broadly speaking, from the early 12th century most full-size monastic houses of whichever order were governed and laid out much as at Castle Acre.

From the 1130s large numbers of new monastic houses were founded in England, 120 in the reign of Stephen and, by the end of Henry II’s reign, a further 30 to 40. By Henry II’s death in 1154 there were around 500. Most of these were new orders and numerically the largest group within them were the canons.11 Unlike most monks, canons were ordained priests who spent some of their time outside the monastery working among local people. There were various groups of canons but the largest were the Augustinian (or Austin) Canons, who eventually had about 200 houses in England. Their buildings were usually modest – although they could be large – and often would share a parish church. Lilleshall Abbey, Shropshire, is still a parish church, but is fairly typical of one of the larger Augustinian priories, built in the 1190s and occupied by ten or eleven canons.

Fig. 64 Rievaulx Abbey, Yorkshire: the east end of the abbey church as rebuilt in 1220–50. The early commitment of the Cistercians to simplicity in life, liturgy and architecture had given way to an intense commitment to the beauty of holiness. The original altar stone can be seen in the centre of the presbytery; behind this was Airled’s shrine and behind this additional altars for the community.

Fig. 65 The Abbey church at Rievaulx, Yorkshire as built 1147–67 showing the liturgical divisions. The monk’s choir was effectively a church within a church.

The most architecturally ambitious order was, however, the Cistercians. Their abbey at Rievaulx is now the most important, interesting and evocative ruined monastery in England. It was founded by Walter Espec, a rich and powerful baron at the court of Henry I who gave 1,000 acres to the new Cistercian order to build a house two miles from his castle at Helmsley, Yorkshire. The first abbot, William, enlarged the community from 30 to 300 in a little over a decade, but its fame and success came through its third abbot, Aelred, probably England’s greatest medieval churchman, who doubled the size of the community to 650 (most of whom were lay brothers and servants).

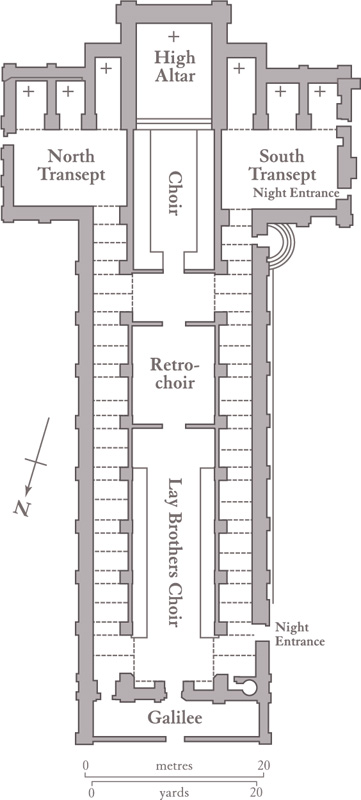

The abbey church lay at the heart of monastic life, the focus of the Opus Dei (the work of God), the eight daily services and the celebration of Mass. Early Cistercian churches were divided into three (fig. 64). The western part was reserved for the lay brothers, who were responsible for the heavy manual work of the abbey. They took simpler vows and attended fewer services. Then there was the retro-choir, divided from the lay brothers by a screen topped with a rood (crucifix); this was reserved for old and infirm monks unable to withstand punishing attendance in the choir day and night. At the east end and under the crossing was the monks’ choir, the hub of the church. The presbytery was in a stubby east end flanked by altars. This arrangement served Rievaulx well for a century, but between 1220 and 1250 a huge new east end was built in the Gothic style. Cistercian churches began extending their east ends from the 1180s and, as we have seen, this was happening in many cathedrals too (p. 96). The work was done with great richness and expense, and reflected the incredibly successful exploitation of the abbey’s estates by successive abbots. As at many cathedrals, Rievaulx’s new east end was built to contain a shrine for their very own saint, Aered (fig. 65). This shrine, which was covered in silver and gold, explains the magnificence of the new architectural work that otherwise might have seemed too lavish for an order devoted to simplicity. The new east end cannot only be explained as an expression of architectural hierarchy, for by the 1220s other factors were involved. There were now few, if any, lay brothers, and so the nave was sealed from the choir by a huge stone pulpitum (screen) and used mainly for processions. Second, despite resisting it at first, the Cistercians were now prepared to offer Masses for the souls of donors (votive Masses), and this meant that more private chapels were required. As about one in three monks was ordained, there were probably 35 priests able to celebrate Mass, for whom five chapels against the east wall would have been a welcome addition.12

Where the Rich and Powerful Lived

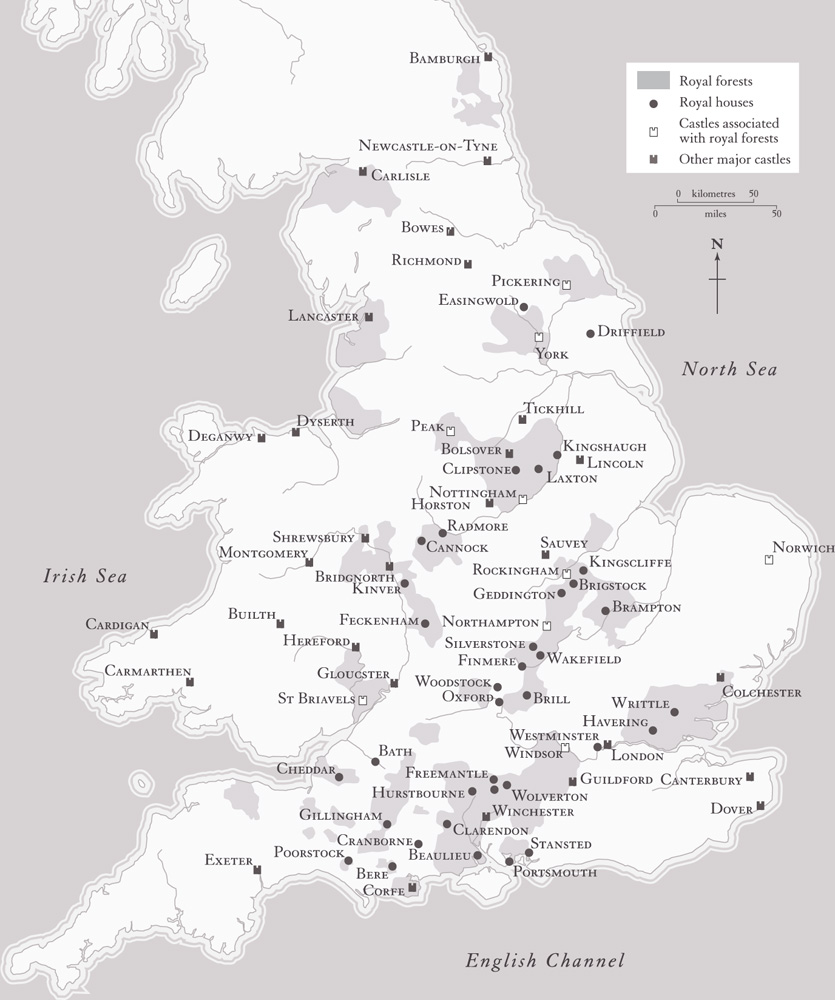

Up to the 17th century kings and their households were constantly on the move. Organising the royal itinerary was a precise task as monarchs spent particular times of the year in specific places, above all during the great religious feasts of Christmas, Easter and Whitsun. They would also want to appear at provincial residences to reinforce their judicial, administrative and military policies and, crucially, to hunt in the royal forests. Royal houses and castles formed the points around which the court gyrated (fig. 66). The king’s preference dictated where they went, what was repaired, built or extended, and when. In each county the sheriff was responsible for organising royal construction work. However, just as bishops and deans employed architects to oversee big projects, so the king had ingeniatores (engineers or designers) in his household. The first of these about whom we know anything was an Englishman called Ailnoth in the 1150s; under him were the master craftsmen, the masons, carpenters and others – all highly paid technical experts, not just workmen. Ailnoth was responsible for Westminster, the most important royal house in England up until 1512, although the precise layout of the palace is unclear before the reign of Henry III (p. 144). The provincial civil residences of the Crown fell into two groups: those large manors that we can legitimately call palaces, such as Clarendon, Wiltshire, and Woodstock, Oxfordshire; and smaller houses situated in royal forests that were used as hunting lodges, such as Writtle, Essex, and Kinver, Staffordshire. Clarendon was the largest and most important royal house in the west. It was excavated in the 1930s, and it is possible to walk through the fields and see substantial chunks of masonry still standing in front of spectacular views of Salisbury.

Fig. 68 Oakham Castle, Rutland; a very rare survival of a great hall of around 1190. It is built like a church with a central ‘nave’ and aisles, though without clerestory windows. The door was originally in the far right bay and the dormer windows are later additions.

Fig. 69 Dover Castle, Kent. Henry II’s Great Tower dominates the castle and is surrounded by a mighty curtain wall with 14 towers and two gates, one of which can be seen in this view. In the foreground are the 13th-century Norfolk Towers and the circular St John’s Tower, while in the background can be seen St Mary in Castro (fig. 34).

While the disrupted reign of King Stephen saw less permanent castle construction, in the reigns of Henry II, Richard I and John this was the largest single item of royal expenditure, consuming ten per cent of royal income. There was serious purpose behind this. First, it was necessary to modernise the forts of the south coast as a protection against invasion, but also as a springboard for continental expeditions and to protect communication routes to the continent. Then it was necessary to protect England’s internal borders against the Scots and the Welsh. Perhaps most important of all was the lavishing of money on strategic royal castles inland. These had been established as the administrative, judicial and financial nodes of the kingdom, and many had become favoured royal residences too. All performed another crucial task, of emphasising royal lordship over both great and humble.

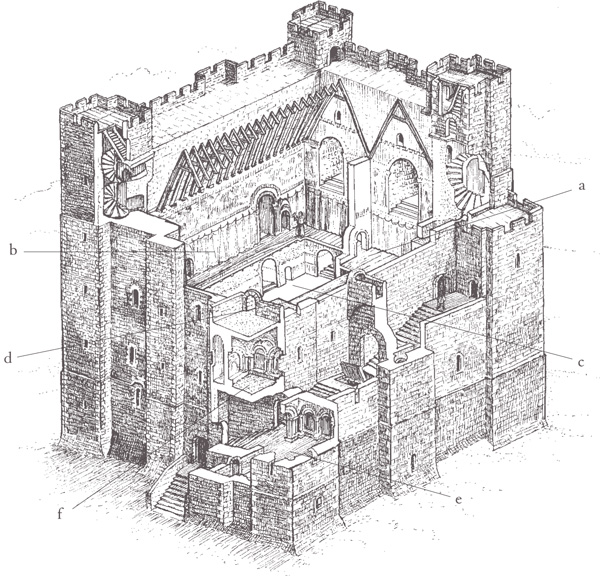

Few new castles were founded after 1130. As both prestige and warfare demanded buildings of stone, it was a period of rebuilding and reconstruction. For Henry II and his successors, the cultural and military value of a great tower was still unsurpassed and so, while many timber castles had their walls replaced in stone, the towers were in many cases a new addition. Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Orford, Peveril and Scarborough castles all acquired great towers, but the last, largest and most expensive was at Dover, where Henry II spent £7,000 between 1180 and 1190. To put this in some sort of context, the total receipts of the royal exchequer in 1130 were £24,500. Dover has a continuous history of fortification back into the Iron Age and perhaps beyond, but no securely dated remains exist before the reign of Henry II. Henry erected his great tower on the highest point of the site surrounded by an inner defensive wall, with 14 projecting rectangular towers and two gates protected by a defensive outwork or barbican. This inner wall was itself guarded by the Iron Age earthworks around it and a short section of wall to the north-east (fig. 69). The great tower was a colossus: nearly square, 83ft tall, with walls between 17ft and 21ft thick. Its silhouette was designed to be seen from France. Inside it does not disappoint. The great tower, like most post-Conquest castle towers, was approached by a fore-building with steps ascending to a second-floor entrance (fig. 70). Refinements in the Dover fore-building include a chapel on the stair, perhaps for giving thanks for a safe journey, a drawbridge, and a guard room by the entrance door. The main building was three storeys high. The ground floor was designed for kitchens and the two floors above contained two magnificent suites of rooms, one for the king on the second floor and another for guests below. Each had a hall and a chamber, and in the massive thickness of the walls were other subsidiary rooms, including garderobes. The king’s floor also had a lavish chapel for his private use. The rooms were architecturally unadorned. Colour and decoration were provided by murals and portable furnishings: hangings, furniture and plate.15 It is worth dwelling on the great tower at Dover as it was the last in the line of great towers built after the Conquest. Henry II constructed it at a time when military engineering had moved away from square and rectangular towers to cylindrical ones. But this was no ordinary castle; it was built in a deliberately retrospective style to emphasise royal gravitas and dynastic durability. It was also a gateway to England, a place where the king could receive important visitors, many of whom were on their way to the new shrine of St Thomas at Canterbury Cathedral. So while this was a military building, it was also a palace and guest house cast in the traditional language of dynastic triumphalism.

Fig. 70 Dover Castle, Kent; the Great Tower: a) king’s hall; b) king’s chamber; c) guest chamber; d) guest hall; e) forebuilding, including chapel; f) chapel.

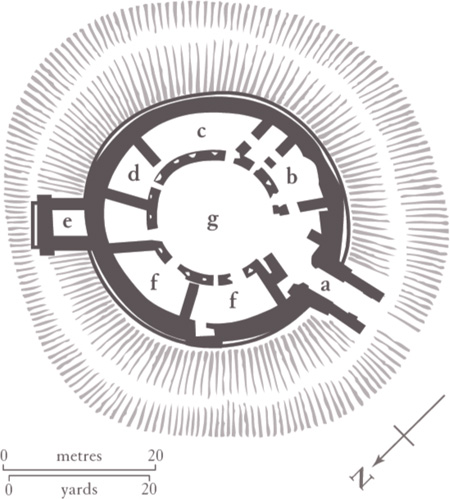

Dover was, of course, exceptional in both its scale and the thoroughness in which it was rebuilt. For many hundreds of other castles, rebuilding in stone took place piecemeal over a long period. In many instances timber palisades were replaced by stone walls, while the residential buildings inside remained of wood. This can be seen at Totnes, Devon, an example of a motte and bailey castle dominating an important trading settlement (fig. 71). It was founded, together with a priory, by Judhael of Brittany, a commander in the Conqueror’s south-west campaign. The timber palisades on top of the exceptionally large motte were rebuilt by his successors in around 1200. The arrangement of the domestic buildings inside cannot now be discerned, but at Restormel in Cornwall the whole plan can be read in a single visit. It is most impressive (fig. 72). The kitchen, hall, lord’s chambers and guest rooms are all arranged inside the perfectly circular outer walls, with only the gatehouse and the chapel projecting outside the circuit. In the 12th century castles were never ordinary residences. Holding a castle proved that the owner was in royal favour with delegated authority to govern and dispense justice. The crown’s ability to take and hold castles, to raise them and demolish them, to grant them out and to take them back was central to the exercise of power. Constructing a new castle required royal permission, and if the king were ever to need it he had the right to requisition it at will. From the 1150s to the 1210s the balance of castle power shifted markedly towards the Crown. At the end of the chaotic reign of Stephen there had been 225 baronial and 49 royal castles. By 1214 there were only 179 baronial castles and the number of royal castles had risen to 93; a shift in ratio from 5:1 to 2:1.

Fig. 71 Totnes Castle, Devon. The motte is what we see today, although there was a bailey with a great hall and other buildings in it. The circular curtain wall was topped with crenellations with arrow slits. Within the wall was at least one domestic building.

Fig. 72 Restormel Castle, Cornwall was topped by a ring of buildings 130ft across: a) gate tower; b) kitchen; c) hall above; d) chambers above; e) chapel above; f) store; g) courtyard.

Getting About

From the 12th century oxen began to replace horses for pulling ploughs and, soon, for pulling carts. Horses could be much faster than oxen but required better roads. By 1066 the Saxon kings had done much to improve the road system and build bridges (pp 25 and 40), but during the 13th century many hundreds of new bridges were built; indeed, of the rivers that were bridged before 1750 almost all had been crossed by 1250. This was certainly a transport revolution but also an engineering one. The technology to build stone bridges was developed by the architects of the great cathedrals, abbeys and castles. Before 1100 most bridges were of timber, such as the impressive bridge excavated over the river Trent in 1993, but during the following century techniques were developed for building foundations underwater, resulting in some impressive feats of engineering. An early surviving bridge, although now tragically marooned in a roundabout, is in Exeter (fig. 73). It was completed by about 1200 and originally had 17 spans of round-headed and pointed arches. The arches were built on wooden piles driven into the bed of the River Exe and protected by triangular cutwaters jutting into the stream. Exeter is typical of a lowland bridge; upland bridges had to withstand flash floods and fast-running waters, and thus had much higher and wider spans. The main arches of Elvet Bridge in Durham, which span over 30ft, were erected in 1228. The bridge, which originally had 14 arches, was commissioned by the bishop and built by his masons. It incorporated chapels at either end (fig. 74).16