The Building of England: How the History of England Has Shaped Our Buildings

So the interior of Westminster Abbey was conceived as a spatial whole rather than an agglomeration of small compartments as in Saxon churches (fig. 33). Its walls, which in an earlier Saxon church would have been a solid mass of masonry acting as a vast canvas for painting, now became an organised system of superimposed arches raised in tiers one above the other. The basic principle of the design was that each arch should be visibly supported by a column (or half-column) and a capital. This produced a clustering of vertical shafts round the piers that visually broke up the hard forms of the structure. The arches themselves no longer had simple square sections but displayed a range of shapes created by the addition of extra rolls and mouldings.

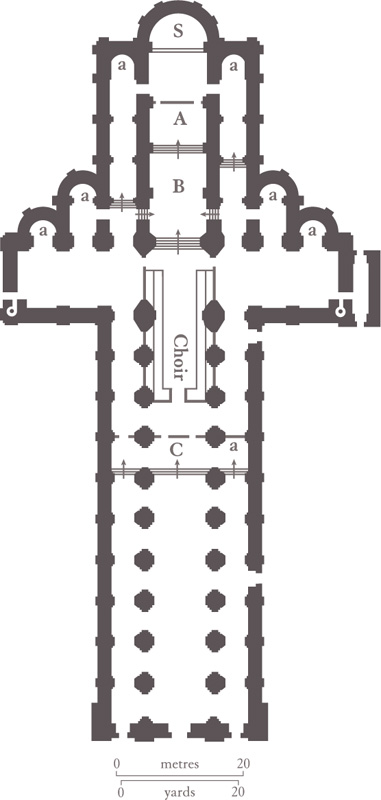

Equally, the plan of the church and abbey buildings at Westminster became the model for the layout of a monastery well into the Middle Ages (p. 98, figs 109, 175). The cross-shaped – or cruciform – church had a large eastern apse and smaller subsidiary apses on the short arms. There was a tower at the crossing and smaller towers containing stair turrets. The conventual buildings (the abbey’s domestic structures) were to the south, with the cloister in the corner between the south transept and the nave, and a chapter house with an apsidal end on the east side. There was a dormitory on the east side and a refectory on the south. Who conceived this new building for Edward will never be known, although the identity of the three most important figures is recorded: two had English names; the third appears, perhaps, to be German. In architecture stylistic change is normally more than a whim of the designer. In the case of Westminster Abbey, Church reform was an important factor (pp 73, 76); the new monastery, in common with its sister buildings in mainland Europe, was to be a model for reformed Benedictine monasticism. Edward’s political and dynastic ambitions have already been mentioned, as has his wealth, but we should never discount the sheer fascination and enjoyment of building things in a new way – and late Saxon Westminster was new and shocking to anyone who saw it.4

Fig. 35 Holy Trinity, Great Paxton, Cambridgeshire, the nave arcade; a mid-eleventh century example of compound piers with bulbous cushion capitals.

In the 1050s local churches began to display similar architectural forms to Westminster and a much stronger spatial unity. At St Mary’s, Stow-in-Lindsey, Lincolnshire, the transepts and crossing of a large minster church of c.1055 still dominate the small village. It is one of the first generation of buildings in which the Anglo-Saxon porticus had transformed itself into a fully fledged transept. The crossing tower at Stow would probably have been made of timber, but at St Mary in Castro, Dover, the masonry crossing tower survives (fig. 34), albeit much restored. A third church, Holy Trinity, Great Paxton, Cambridgeshire, not only has transepts and a crossing, but its nave has aisles with an arcade of compound piers (fig. 35). This small group of churches might once have been part of a larger family experimenting with new forms and spatial concepts, but it is likely that these architectural adventures were confined to the highest level of patronage; Great Paxton and Dover might have had been commissioned by the king, while Stow was founded by Earl Leofric and his wife Godgifu (Lady Godiva).

Patrons lower down the social scale, however, were also very active. After 1000 thousands of local churches, originally constructed in timber, were rebuilt in stone. This fashion was started by the rich landowners of commercially developed East Anglia, but soon spread to the nucleated villages of the Midlands and then eventually to western England. This was an important moment in English architectural history. On the one hand, it shows that there were now builders who could produce a sort of standard, ready-to-order stone church; on the other, it meant that more and more ordinary people started to experience complex and elaborate stone architecture on a daily basis. There was a liturgical change, too. Most of the earlier timber churches were single spaces, but the separate chancels in the new stone churches meant that the priest was separated from his congregation. This created a different relationship between congregation and priest, who now had an elevated status. Meanwhile, the nave became a communal space in which people congregated to celebrate and to mourn. From the late 10th century local churches had their own burial grounds and from around 1050 permanent fonts.5 It will never be possible properly to judge the architecture of late Saxon England, as the vast majority of it was swept away after 1066. Yet what survives suggests that after 1000 a new aesthetic began to gain ground: a greater spatial harmony and a new architectural vocabulary. Much of this was promoted by a tiny super-rich elite, the structure of which was England’s political Achilles heel: Saxon England was systemically weak, unable to settle the key question of succession. That weakness was exploited by Duke William of Normandy in 1066. Conquest The Norman Conquest looms large over English history, casting a shadow that obscures much of what came before and colouring what came after. It sounds obvious to say it, but in the year 1000 no one had heard of the Norman Conquest. In fact no one had heard of the Normans as such; to the English the people of Normandy were French. England and Normandy faced each other across the Channel, sharing a common cultural inheritance, both greatly influenced by Scandinavia. England was richer and bigger, and was experimenting with exactly the same types of architectural novelty as the Normans. I have already suggested that the term ‘Romanesque’ is not very helpful in trying to characterise Anglo-Saxon architecture (p. 39), so this book does not use it. The same applies to what was built after 1066, which is normally categorised as Romanesque and commonly called Norman. Sadly, this too is simplistic and confusing, suggesting as it does that the buildings erected in England after 1066 were somehow in a style that was brought over by the Normans. They were not. What is normally called Norman architecture was developed in England after 1066, drawing on native traditions and absorbing influences and ideas from across Europe, so it can more properly be called Anglo-Norman or Anglo-French. It was an inventive, eclectic, exotic and cosmopolitan style born of a unique coincidence of political, religious, social, cultural and economic events. English architecture for a period of fifty years was among the most original and influential in Europe.6

Fig. 40 Freestanding bell tower at St Mary’s, Pembridge, Herefordshire. This late 14th-century tower is supported internally by eight mighty oak posts forming a square. They are braced diagonally and horizontally up to the pyramidal roof. Though this is a much later example, the footprints of such massive timber constructions have been excavated and dated to the 11th and 12th centuries.

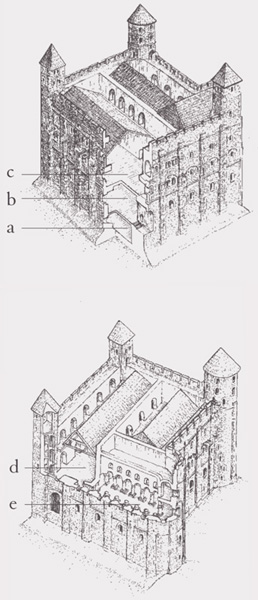

Two buildings started by William, however, were – the White Tower, London, and its sister in Colchester. These colossal structures were palaces for the duke-made-king. They contained a suite of reception rooms and a large chapel in an overwhelming stone-built tower. Such towers had been built for rulers before in the Loire valley and, indeed, in Normandy itself, but not quite on this scale or to this level of sophistication. In fact, scale was integral to their purpose; the parapets of the White Tower were raised far above its roof line to create a more domineering silhouette (fig. 37). The population of London, as the largest and most important city, and that of Colchester, guarding the east flank of England from troublesome Scandinavia, would be in no doubt that their new king was a mighty and determined master. Yet these were sophisticated residences, too. They had fireplaces with chimneys, garderobes (latrines) and simple, bold architectural settings for thrones, tables and chairs. Furnished with rich textiles, brightly painted wooden furniture and sparkling with candlelit gold plate, these palatial towers were intended to be a pleasure to live in as well as a mighty image of royal power. The White Tower ranks as one of the most important buildings in English architectural history. Its direct influence was to be felt in the design of castles for more than a century and its effects on London continued for more than half a millennium.12

Great Churches: The First Phase

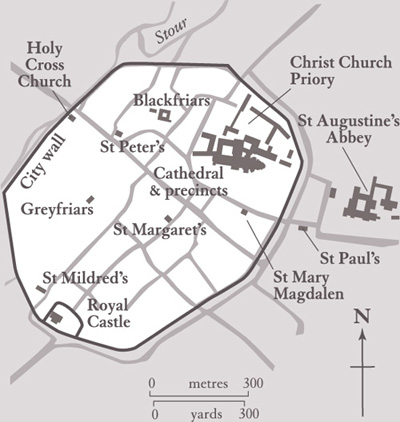

In England and Normandy of the 11th century there was no hard distinction between Church and state. While the pope kept an eye on doctrine, lay rulers effectively governed their national Churches. Both William and Edward the Confessor were interested in Church welfare and reform, and welcomed a series of reforming decrees starting in 1049 that slowly transformed canon law and liturgy in Western Europe. William had promoted reform in Normandy from about 1050 through his chief religious advisor, the Italian abbot Lanfranc, one of the greatest intellectuals of his day, and when William sailed from Normandy in 1066 he did so under the banner of the pope. Once in England, William used his power of appointment and patronage ruthlessly. He appointed Lanfranc as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1070 and, in a series of councils between 1072 and 1076, the structure, governance and morals of the English Church were reformed.13 This was as much a political as a moral crusade; with William’s support Lanfranc reorganised the boundaries of Saxon dioceses, moving cathedrals from the countryside to towns and ensuring that the diocese became, like the county, a unit of government control. So the Saxon cathedral at Dorchester-on-Thames moved to Lincoln, Selsey to Chichester and Elmham to Norwich, via Thetford. By the reign of Henry I there were 17 dioceses, with boundaries that remained nearly unchanged until the Reformation (fig. 41).

Fig. 41 English dioceses in 1100; several, such as Lincoln and York, were huge compared to their modern size.

Within a period of less than 50 years each of these dioceses was to have an entirely new cathedral, perhaps the largest and most ambitious programme in English architectural history. It is easy to imagine that this meant the invention of a new type and shape of church, but there was no simple change from ‘Saxon’ cathedrals to ‘Norman’ ones. The sixteen cathedrals built between around 1070 and 1130 were not identikit structures; each mixed stylistic and liturgical influences in its own way according to the preferences of its bishop, the resources available and local traditions. This had probably not been Lanfranc’s intention. He had hoped to abolish Anglo-Saxon forms and traditions, and bring the liturgical and architectural life of English cathedrals into line with the most advanced thinking on the continent. In this, Canterbury was to be the model. Lanfranc’s Canterbury Cathedral was the most derivative of all the great churches built after the Conquest. Lanfranc had been the abbot of St Etienne at Caen and had overseen the reconstruction of the abbey church there; his cathedral at Canterbury was closely modelled on his old church, right down to the precise dimensions of the transepts and nave. But this was not just an architectural importation. The archbishop set down the liturgical practices he wanted performed in his new country: the Decreta Lanfranci was to replace the Saxon Regularis Concordia (pp 44–5) as the liturgical rule book for the English Church. In composing this, Lanfranc, who had trained as a lawyer and taught logical disputation (dialectic), turned away from the showy, flowery customs of the Saxons and set out a more austere, simpler and more disciplined liturgy. Lanfranc did not have the authority to impose this on everyone, but soon at least 15 monastic houses followed his rules.

Other than a few fragments, Lanfranc’s cathedral at Canterbury has been completely rebuilt, but remarkably the liturgical arrangements implemented by him can still be appreciated by visiting the abbey church at St Albans, Hertfordshire, which was started in 1077 (fig. 42). Here there are three liturgical foci: the high altar at the east end; a choir altar for lay people facing the nave; and a huge crucifix (or rood) over the pulpitum (the screen that divided the choir from the nave). At St Albans, as at Lanfranc’s Canterbury, relics remained hugely important and, just as in Saxon churches, the organisation of large numbers of pilgrims had a major impact on the design. The most important relics were either in a crypt below the east end where pilgrims would not interfere with the daily round of monastic services, or, as at St Albans, east of the high altar in a screened enclosure. This definitively divided the church into the part for the monks (the screened-off choir) and the parts for the laity (the nave for services, the shrine at the east end for pilgrims).14

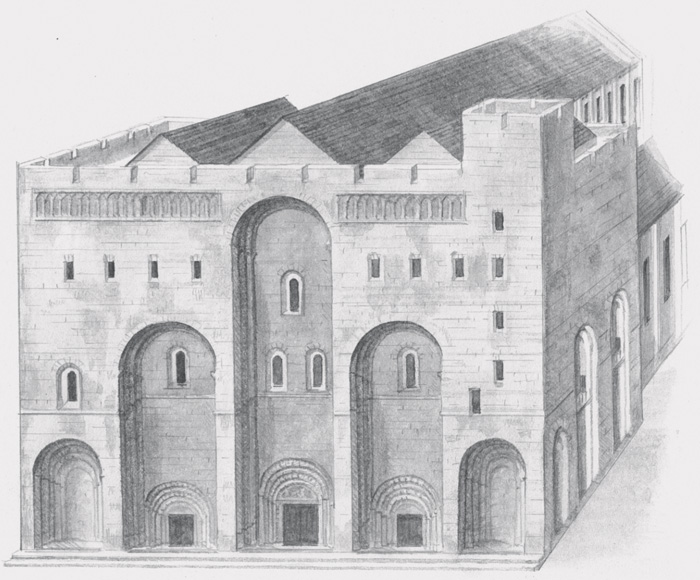

Whilst a minority of churches followed the liturgical arrangements of Canterbury, most had a more sympathetic attitude to Saxon customs. Several new cathedrals preserved the idea of the westwork, providing a secondary focus at the west end. The most spectacular of these was at Lincoln, where the west end was a massy, semi-fortified bishop’s hall, echoing a Roman triumphal arch (fig. 38). At Ely, too, a great central tower and part of a western transept survives. We know that at Winchester there was a western structure, now lost. These same cathedrals, like Saxon ones, had extensive areas of first-floor liturgical space for processions and altars. It was possible to do an entire circuit in the broad first-floor galleries at Winchester, and its upper altars were approached by spiral stairs just as in Saxon churches (fig. 43).15

Fig. 42 Abbey Church of St Alban, St Albans, Hertfordshire, reconstructed plan showing liturgical arrangements in around 1100: a) side altar; b) relic repository; A) high altar; B) matutinal altar; C) rood altar; S) shrine.

At Winchester one can still gain a good impression of what the interior of the first generation of post-Conquest cathedrals looked like. In the 11th century there was no such thing as a capital city; Norman kings governed as they moved around the country. Yet Winchester, as the seat of the kings of Wessex, had a claim to be the traditional seat of the English monarchy (p. 48). William seems to have acknowledged Winchester’s special status; he rebuilt the royal palace and constructed a castle. He was crowned at Winchester, too, for a second time, by two cardinals and a papal legate, and later his son Rufus was buried there. William also had a permanent treasury at Winchester, and at Easter time the cathedral was the location for one of the thrice-yearly royal crown wearings.

So it is not surprising that in 1070, when the Saxon Bishop of Winchester, Stigand, was deposed, the new bishop, Walkelin, resolved to rebuild the cathedral, emphasising the importance of the city and its royal associations.16 Foundations were laid in 1079, and by the time it was finished it was the largest cathedral in Europe, its dimensions almost identical to those of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome (fig. 43). The church was cruciform, with transepts as wide as the nave. There were towers at the west end, on the corners of the transepts and over the crossing. Today only the transepts survive from Walkelin’s time (fig. 44), but here the essentials of the style of the new cathedral can be appreciated. Like the Confessor’s Westminster Abbey, the elevations are three storeys high: a main ground-floor arcade, a gallery above and, crowning that, a clerestory. These levels are tied together by mast-like shafts that rise to the roof. Within this the individual parts of the elevation are subordinated to the whole. The arches at gallery level, for instance, are contained within a larger arch and the whole bay is bounded by piers running from floor to ceiling. The conglomeration of shafts, which visually fragment the piers, disguises the fact that they are, in fact, huge, thick sections of wall supporting the galleries and clerestory above.