The Building of England: How the History of England Has Shaped Our Buildings

The Parishes

The period after the Conquest saw a huge shift in wealth from secular hands to the Church, a shift in landownership not equalled again until the reverse took place under King Henry VIII. Thus Norman landowners such as Robert and Beatrice, the landlords of Asheldham, Essex, endowed their church of St Lawrence by transferring its patronage to a local priory at Horkesley with sixty acres of land. Many such gifts were stimulated by the penitential ordinance of Easter 1067, which set out the penances owed by William’s men who had killed and maimed on English battlefields. Those who were unclear how many English they had slain had a choice: they could either do penance one day a week for life or endow a church. If you were rich the choice was easy.17

This lent additional momentum to the rebuilding of timber churches in stone that had started around 1000 (p. 68). At Asheldham the timber church was replaced, the main street diverted and a burial ground formed. Asheldham church has now been rebuilt, but a small number of churches rebuilt soon after the Conquest have been preserved largely unaltered because of later depopulation. Such churches vividly capture the everyday experience of worship in the years immediately after the Conquest.

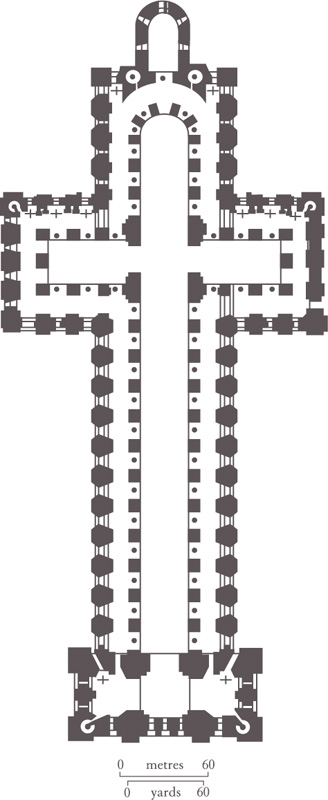

Fig. 43 Winchester Cathedral, plan at tribune (first floor) level. The cathedral, begun in 1079, had many affinities with its Saxon forebears: there were altars in the galleries and a tribune or royal pew at the west end. Spiral stairs led up to the gallery at several points. + indicates a side altar.

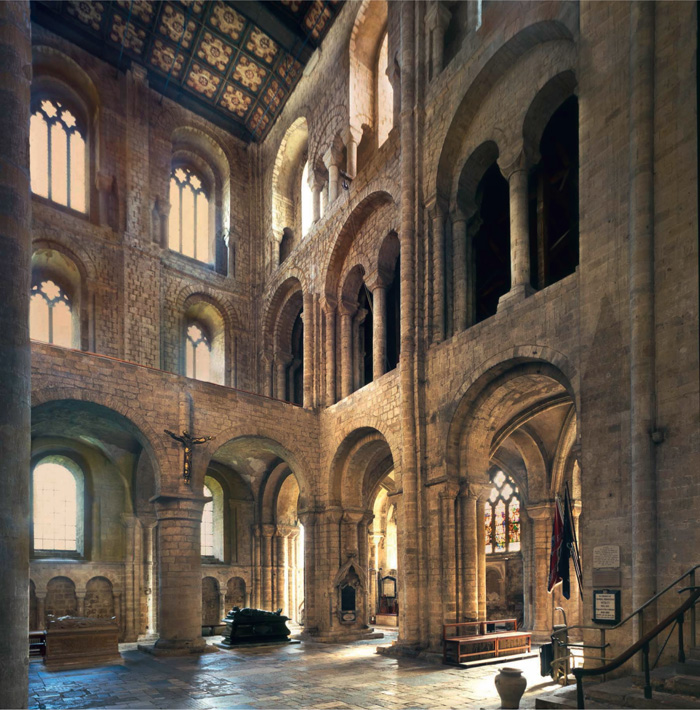

Fig. 44 Winchester Cathedral; the north transept. This precious surviving unaltered part of the cathedral shows the raw simplicity and power, almost crudeness, of the early Norman cathedral.

Fig. 45 St Margaret’s, Hales, Norfolk. This lovely church has a Saxon round tower that was heightened in the 15th century, but its nave and apsidal chancel date from the early 12th century.

Fig. 46 St Botolph’s, Hardham, West Sussex. The wall paintings here, done in 1120–30, were covered up in the 13th century and only re-discovered in 1866.

Most of these are two-roomed (or, more correctly, two-celled), with rectangular naves separated from the chancel by an arch. Most chancels originally had an apse but almost all were later rebuilt square-ended. In east Norfolk a couple of remote churches still retain their original apse, and perhaps the best among these is St Margaret’s, Hales. The round tower is later, but the apsidal chancel dates from before 1130 and retains some of its blank arcading (fig. 45).18 Another group of well-preserved churches is in West Sussex. St James’s, Selham, could be Anglo-Saxon; its masonry and carving are clearly by Anglo-Saxon hands, although the likelihood is that it was built just before 1100. St Botolph’s, Hardham, miraculously retains its wall paintings of about 1120 that were whitewashed over and only rediscovered in 1866. The murals, painted in ochre and yellow, a typical Anglo-Norman bacon-and-egg palette, show St George slaying the dragon (the earliest such image in Britain), and wonderful figures of Adam and Eve (fig. 46). The halos are painted in green paint made by coating copper plates in urine and sealing them in a container for two weeks.19

Although these small Norman churches are sometimes almost indistinguishable from their Saxon predecessors, the difference was the discipline that the Normans sought to bring to parish life. Lanfranc’s reforms subdivided dioceses into archdeaconries and deaneries to give greater supervision to individual parish priests. This was important, as most priests before 1000 were in minsters under close supervision; with the proliferation of local churches there were now hundreds of remote priests, poor, ill-educated (often illiterate), undisciplined and isolated. Some were drunkards, some said Mass armed, others had secular employment and many had wives. Almost all were English. Under the new regime more was demanded of them and greater discipline enforced. The life of the average clergyman was transformed in the century after 1066.20

The Towns

The impact of the Norman Conquest on English towns was enormous, physically, economically and socially. Saxon lords who had lost their country estates lost their urban lands (burgages) too. In the place of English burgesses Norman landlords settled, and in the place of English town houses new castles, cathedrals and priories rose. Many of these, such as those at York and Winchester, were instigated by royal command; others were the random and illegal acts of new landlords. Norwich was already one of the largest towns in England in 1066 and was to become even more important when the see was transferred there from Thetford. By the time of the Domesday Book in 1086 almost half of the Anglo-Saxon town had been cannibalised for the Norman castle, cathedral and new housing. One hundred and thirteen houses were demolished for the site of the castle alone, and 32 English burgesses – bankrupted by the seizure of property and royal tax – fled the town.21

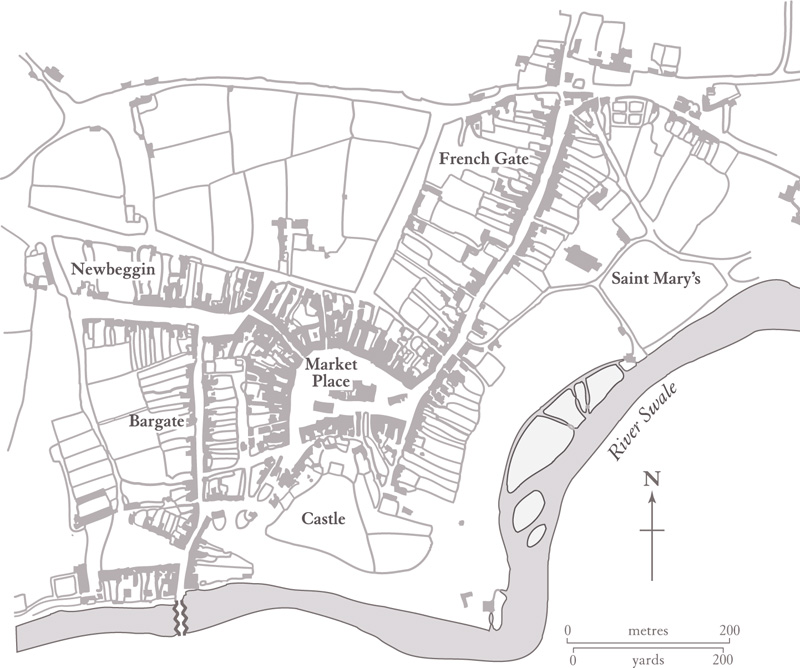

As castles and cathedrals rose, existing towns were re-planned. At Richmond, Yorkshire, a vast castle covering 2 ½ acres was grafted on to a small, pre-existing settlement. Against the castle gate was laid out the market place, and on to this, in a D shape, the burgage plots of the townsmen (fig. 47). There is no doubt that Richmond was founded on the top of a cliff for military reasons, but the town was designed as an economic engine for Alan Rufus, who began the castle in 1070. Richmond was at the centre of a huge network of arable estates and soon became not only the principal market but also an industrial centre.22

Fig. 47 Richmond, Yorkshire: plan of the town based on a map of 1773. There are two centres to this town, the original village core round St Mary’s Church on the east side and the semicircular castle borough to its west. Though the castle is perched on a dramatic cliff falling to the river Swale, the reasons for its location were as much economic as military.

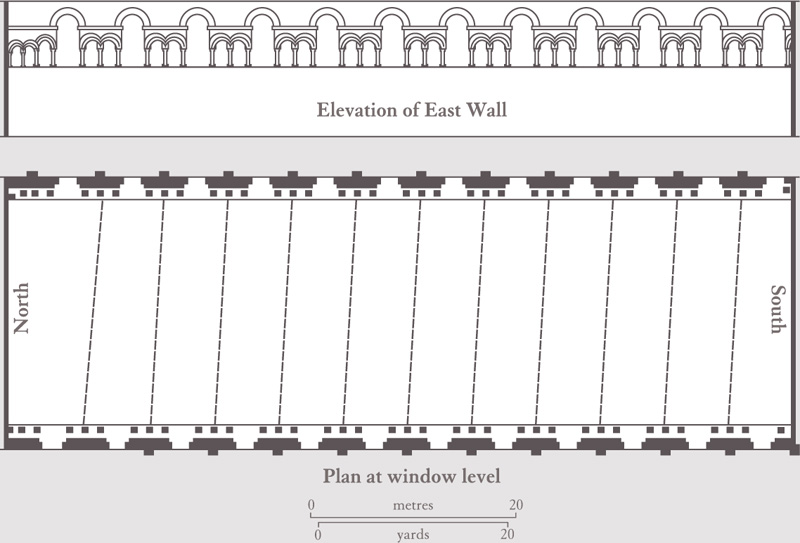

New abbeys could have a similar impact. At Bury St Edmunds the colossal new abbey church (second only in size to Winchester) had a decisive influence on the town. The monumental abbey gatehouse provided the kingpin for the town grid (fig. 48).23 Many of these extensions and remodellings were to be economically successful. At Bury the Domesday Book entry tells us that in 20 years the town had grown by 342 houses. Much of this was as a result of the economic stimulation of the construction industry, the effects of which in a town such as Bury or Norwich must have dominated the local economy for decades. The Death of the Conqueror William the Conqueror died in 1087 and the succession was split between his three surviving sons: Robert, William Rufus and Henry. Robert inherited Normandy but pawned it to his brother William when he went on crusade in 1096. William Rufus thus became king of England and, for a few years, controlled Normandy. In 1100 Henry succeeded Rufus as king and in 1106 seized Normandy from Robert, throwing him in prison. Henry died in 1135, the year after his brother. William Rufus’s reign saw a reaction to the highly militarised nature of his father’s time. There was an explosion of decorative excess. Rufus’s court was known for its outlandish fashions: long hair, tight-fitting tunics, drooping cuffs, and shoes with long, pointed, curly toes. This sense of exuberance can still be felt in the fabric of his most important building, Westminster Great Hall. The ceremonial centrepiece of the Norman palace at Westminster, at 240ft long by 67.5ft wide it was the largest secular space in northern Europe. Outside, fearsomely tall stone walls were topped with a decorative band of chequered stone and crowned with a blind arcade. It was entered, not on one of its long sides as was normal for such halls, but at the north end, giving a much greater processional focus. Inside, at clerestory level, there were pairs of small arches set under larger ones as at Winchester Cathedral (fig. 44). The capitals of these were richly carved and brightly painted, and below, on the great blank wall, would have been paintings or hangings to give the hall a feeling of vitality and colour. The roof was probably carried by a series of vast timber trusses, themselves presumably painted and decorated, and the floor was probably of rammed earth, allowing for the entry of mounted knights. This was never a space for regular use. It was rather a ceremonial hall conceived as the setting for the great feasts that accompanied major religious festivals. In here William wore his crown in splendour and presided over his magnificent household as God’s elected ruler.24

Fig. 50 Peterborough Cathedral nave; the flat wooden ceiling dates from c.1230 and is painted with images designed to be read from the nave far below. Colourful, expressive and a precious survival, it never succeeded in architecturally drawing together the great arcades of 1160–90.

Fig. 51 Durham Cathedral nave, unlike Peterborough, is visually united by its vault. We don’t know who the designer was, but here force and splendour are coherently combined as nowhere else in medieval England. Rib vaults were first erected in the Durham choir in 1095 and were a ground-breaking advance of European importance. The ribs have their own structural integrity and the cells between are made of lighter material 12–18 inches thick.

The Anglo-Saxons had a rich tradition of carving in stone, but their sculptures were either freestanding or used as applied ornament, rather like a bejewelled clasp on a cloak. The new architectural forms developing in Normandy and England in the years around 1066 integrated sculptural decoration into architecture, and blended the roles of sculptor and mason. Architecture after 1066 introduced new opportunities for sculptural embellishment. Whilst Anglo-Saxon doorways were plain rectangular openings in plan, after the Conquest they were routinely recessed, with small columns and capitals supporting moulded arches. These often enclose a stone slab called a tympanum, which provided an opportunity for a virtuoso display of carving (fig. 53). Likewise the capital, a ubiquitous and essential element of the new style, was a vehicle for carving. The vault of Archbishop Anselm’s crypt at Canterbury rests on a forest of carved and decorated columns, each crowned with a sculpted capital; the best, such as the one showing a wyvern fighting a dog, are bursting with energy and motion (fig. 54). The style of these capitals is so close to the initial letters in manuscripts painted in the priory that they must have been designed by the same hands. These were exceptional; most capitals were of a type known as ‘cushion’, a squashed cube of stone that could be painted, carved or more usually left plain. These were rare in Normandy and, as used in England, were probably copied from Germany. They were easy to reproduce quickly in places where the skill, time or money was not available for anything more elaborate.

Fig. 52 Norwich Cathedral; the spectacular crossing tower was the last part of the cathedral to be completed in around 1140; it was erected only after the foundations of the crossing had been allowed to settle, thus avoiding the sort of collapse that had been experienced at Winchester or Ely. The turrets at the corners are part of the original conception – the spire was added in the 1480s.

Sculptural traditions after the Conquest, as with architectural ones, were cosmopolitan, and masons working on the great cathedrals blended influences from Normandy, Burgundy, the Loire, Germany and Scandinavia to produce a rich variety of forms. The most expressive example of this is a group of churches in Herefordshire. One of these, St Mary and St David’s, Kilpeck, displays 85 carved corbels, as well as carved door and window surrounds (fig. 53). Here a Scandinavian great beast with a snake-like body and a dragon’s head winds its way through the stems of a plant of Anglo-Saxon decorative origin.25

Fig. 53 St Mary and St David, Kilpeck, Herefordshire, one of the most perfect 12th-century churches in England. The richness of its decoration, done in the 1130s, is due to the patronage of Hugh of Kilpeck, the Lord of the Manor who also built a castle next door and founded a nearby priory. The south door has a tree of life in its tympanum and otherwise is a writhing mass of dragons, birds, lions, serpents, with the addition of angels and a phoenix.

Fig. 54 Canterbury Cathedral, Kent. St Anselm’s Crypt was unaffected by the fire of 1174 and perfectly preserves the exuberance of the Canterbury masons in around 1100. The subject of most capitals is fighting beasts which give them a restless, writhing quality.

Despite our ability to visit many of these buildings, none gives the modern spectator anything other than a ghost of what was intended. Like Saxon churches, Anglo-Norman cathedrals were filled with colour and texture. Most important were wall paintings. At Canterbury Cathedral the apse of St Gabriel’s chapel was walled up in the late 12th century, preserving – untouched – a complete set of wall paintings only rediscovered in the 19th century. Here it is possible to gain some sense of the brilliance of the painters working in c.1130. The scenes, set out in bands and with strict symmetry, show the annunciations to Zachariah and the Virgin presided over by Christ in Majesty. Vast areas of cathedrals familiar to us as plain stone halls would have glowed with colour, walls would have been whitewashed and imitation masonry blocks outlined in red. Windows would have thrown a coloured glow onto all this splendour, as most were glazed in coloured glass. Along with the glass, almost every scrap of painted woodwork, embroidered textile and gilded metalwork that gave sparkle to early Anglo-Norman cathedrals has gone. Contemporary illuminated manuscripts are now our guide, in miniature, to the sensory delight of these great interiors.

The Establishment of Castles

William the Conqueror died knowing that the military conquest of England was complete and that a matrix of royal castles secured his power in its county towns. There were remarkably few new castles built during the following century; royal architectural attention had turned to Normandy, where the military imperative now lay. In England many castles, such as Canterbury, remained nominally in royal hands but in practice were under the control of constables or sheriffs. One still in royal hands was Norwich, newly elevated to the capital of a diocese.

Fig. 55 Norwich Castle Keep, though extensively repaired and restored by Anthony Salvin in 1835–9 its external elevations still exude the flamboyance and excess of the years around 1100.

Norwich, as we have seen, was England’s second town (p. 77), and the construction of a palatial tower there by William Rufus is a parallel to the White Tower in London. But the Norwich tower was more audacious. It was sited on a high artificial mound or motte, linked to an outer bailey by a giant arched bridge. The same masons worked on the tower and on the cathedral, and the architectural exuberance of Rufus’s reign is apparent in both. Although the tower has been refaced, a series of watercolours of 1796 shows a building without corner turrets, but with massive buttresses framing an intricately composed decorative façade. Inside, the plan centred on a great ceremonial hall lit by high windows.26

These towers were very much a feature of the first generation of Norman overlords. There is scant evidence that the White Tower was ever used as a regular residence, and many, such as Norwich, had long interruptions in their construction. Others, such as Colchester, remained unfinished. The vastness of these structures, conceived in a militarised society for feasting, security and image, was becoming unnecessary as quickly as they were built. But the image of power they were able to convey remained a desirable and fashionable accessory for more than a century to come (p. 102). Two of Henry I’s courtiers demonstrate the allure of the great tower. In the 1120s Geoffrey de Clinton, chamberlain and treasurer to Henry I, was granted lands in Warwickshire, where he founded a castle and priory. The castle at Kenilworth was hugely ambitious and was bankrolled by the king, who wanted to establish it as a royal centre of power against the nearby Earl of Warwick, who was of doubtful loyalty. A great tower was erected and an inner courtyard enclosed around it by a wall. At Portchester, Hampshire, another Norman magnate, Hugh Pont de l’Arche, replaced the Saxon residential buildings inside the Roman walls in the 1130s with a square-plan great tower with a hall at first-floor level.27

Building Materials and Technology

The 11th century saw a revolution in English building. The reconstruction of thousands of local churches in stone and, after 1066, the rebuilding of the cathedrals meant a huge expansion in all branches of stone production. The quantity of stone required to sustain this boom was colossal, perhaps even greater than that quarried by the Egyptians for the building of the pyramids. We have already seen that Saxon quarries generally only produced rubble and small quantities of cut stone, but the effects that architects were trying to achieve from the 1050s onwards demanded much more cut ashlar (i.e. rectilinear blocks). These ashlar blocks formed the internal and external structural walls, with an internal core of rubble mixed with mortar. Much of the expense of stone building was the cost of bringing it to site, so great efforts were made to secure stone locally. At Battle, Sussex, William the Conqueror first contemplated importing stone from Normandy for the construction of his abbey but found that stone could, in fact, be quarried nearby. This was ideal; in many instances, however, the solution was not so straightforward. In Kent, where the local building stone is less suitable for ashlar, Archbishop Lanfranc turned to other sources of stone for Canterbury Cathedral. Whilst the rubble core work could be extracted locally, ashlar came by sea from Caen in Normandy, Quarr on the Isle of Wight and from Marquise near Boulogne.28

If stone had to be moved more than about 12 miles by land the cost of carriage exceeded the value of the stone and so it was better to bring it in by water, a slower but cheaper solution. Before the Conquest canals were cut to bring stone from the Peterborough area to Fenland abbeys. A sunken barge excavated at Whittlesey contained large blocks of Barnack stone perhaps destined for Ramsey. After 1066 many more waterways were dug and diverted to make the movement of stone easier. Much of the stone for Norwich Cathedral was brought by sea to Great Yarmouth and then put into barges that came right up to the cathedral by means of a new canal.29 Whilst new sources of stone were found and old ones continued to be exploited, the plunder of Roman buildings continued. Lanfranc’s Canterbury also made use of Roman brick and tile, and in 1077 the abbot at St Albans found stockpiles of already salvaged Roman materials. Meanwhile, a cathedral such as Winchester, which was largely built of relatively local Quarr stone, made use of the masonry of its Anglo-Saxon predecessor.